Readers of this blog may have noticed sometimes it takes a month or more to find a book/prose I love to blog about. These past few weeks have been a literary bonanza!

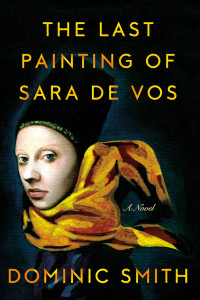

Real and fake, art’s enduring power — three lives, three continents, three centuries (Dutch Golden Age mid-1600s, Manhattan late 1950s, Australia 2000): Dominic Smith is a fictionist who paints beautiful images with words. His brushstrokes are so smooth, deft, and believable you’ll think the “landmark painting” at the heart of his fourth historical novel is the real thing. You can easily picture the “cult classic” hanging in the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, where the largest collection of Dutch art from its golden era is housed. Doesn’t the art specialist’s elegant summation of the seductive image, which opens the novel, seem straight out of an exhibition or sales catalogue?

Real and fake, art’s enduring power — three lives, three continents, three centuries (Dutch Golden Age mid-1600s, Manhattan late 1950s, Australia 2000): Dominic Smith is a fictionist who paints beautiful images with words. His brushstrokes are so smooth, deft, and believable you’ll think the “landmark painting” at the heart of his fourth historical novel is the real thing. You can easily picture the “cult classic” hanging in the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, where the largest collection of Dutch art from its golden era is housed. Doesn’t the art specialist’s elegant summation of the seductive image, which opens the novel, seem straight out of an exhibition or sales catalogue?

At the Edge of a Wood (1636)

A winter scene at twilight. The girl stands in the foreground against a silver birch, a pale hand pressed to its bark, staring out at the skaters on the frozen river. There are half a dozen of them, bundled against the cold, flecks of brown and yellow cloth floating above the ice. A brindled dog trots beside a boy as he arcs into a wide turn. One mitten in the air, he’s beckoning to the girl, to us. Up along the riverbank, a village is drowsy with smoke and firelight, flush against the bell of the pewter sky. A single cataract of daylight at the horizon, a meadow dazzled beneath a rent in the clouds, then the revelation of her bare feet in the snow. A raven – quilled in violet and faintly iridescent – caws from a branch beside her. In one hand she holds a frayed black ribbon, twined between slender fingers, and the hem of her dress, visible beneath a long gray shawl, is torn. The girl’s face is mostly in profile, her dark hair loose and tangled about her shoulders. Her eyes are fixed on some distant point – but is it dread or the strange halo of winter twilight that pins her in place? She seems unable, or unwilling, to reach the frozen riverbank. Her footprints lead back through the snow, toward the wood, beyond the frame. Somehow, she’s walked into this scene from outside the painting, trudged onto the canvas from our world, not hers.

Smith also fools us into thinking he’s an expert in art restoration and forgery (he went to art school). The language of an Old World conservator or fabricator — lead-tin yellow, rabbit pelts, gesso, impasto, mastic, copal – colors the prose.

I also marveled at the assuredness of evoking “sense of place” in distant settings and time periods — Amsterdam’s ancient canals and “Frisian sense of forbearance” and Australia’s modern harbors and changing attitudes toward women in the arts – swiftly moving the reader back and forth in time and place effortlessly. (I’m presuming here that Manhattan’s Upper East Side and Brooklyn, circa late 50’s, the third backdrop and timeframe, is more knowable). Research is one thing, clearly on display, but juggling and blending time/place traveling chapters seamlessly is another. Sure enough, I discovered Smith lived in Amsterdam and was born in Australia, which helps to throw light on his writerly gifts.

Judith Leyster, Self-Portrait c. 1630

via Wikimedia Commons

Smith tells us he imagined Sara de Vos as an amalgamation of a few Dutch women artists from the 1600s including: Judith Leyster, chief among them, as she was the first woman admitted to the governing, highly influential Guild of St. Luke and for 200 years her work had been attributed to her husband, Frans Hals; and Sarah van Baalbergen, whose art did not endure. (Interestingly, Barent was the name of both husbands of the real/imaginary Sarah/Sara.)

Prior to reading the novel, the only Dutch artists from that luxuriant era, a “fluke of rheumatic temperament and history,” I was familiar with were Rembrandt and Vermeer. I’m not sure which statistic is more amazing: the 5 to 10 million works of art estimated to be produced during this renaissance, or the 1% or less likely to have survived?

Heartening, at least fictionally, is the suggestion that another landscape painted by a 1600s-Dutch woman still exists. Though even that’s a question mark, one of many, since these artworks were typically unsigned, and it was not the custom for women to paint landscapes. Still lifes and portraits yes, but women were too housebound to have idle time to wander about outdoors to paint moody scenery. Is the attribution to Sara de Vos correct? If so, who might the ghostly girl be? What if Sara created other landscapes? Might any still exist?

The historical inspiration for this “godly and omniscient” canvas came from the ice-skating scenes of Hendrick Avercamp, an early Dutch landscape painter. (Also heard on the author-interview podcast cited above.)

Winter Landscape by Hendrick Avercamp, first half 17th c., via Wikimedia Commons

Treatment of women is a recurring theme. First with Sara, whose harsh circumstances in the Old Country unfold a likely scenario that could have led to her extraordinary artistic license, working under the strict auspices of that almighty Guild. Fast forward centuries later to Ellie Shipley, art historian/restorer/one-time forger of a “meticulous fake,” who immigrated to New York from her native Australia and London’s Courtauld Institute of Art to gain respect in a male-dominated field. In the late fifties, when she commits the art crime, she’s in her twenties doing her dissertation at Columbia on Baroque Dutch women painters, drawn to the progressive school’s two-female faculty. How she came to copy the painting in her squalid Brooklyn apartment that smelled so badly from the glues, paints, and varnishes she concocts to mimic the Dutch masters becomes a window into the techniques, obsession, and mindset of a painstaking forger, whose “dominion is theater and subtext.” Forty-years later, when we meet her again teaching at Sydney University and curating an exhibit on her specialty, she’s achieved stature. But her soul has suffered the burden of her shameful deed all these years.

Revenge for stealing the painting takes on a deceitful, fervent life of its own that plays out with a feminist angle, conceived by our main male character: fortyish, wealthy, New York patent attorney Martin de Groot, of Dutch ancestry. He inherited the painting from his father, passed down generations. The affecting painting hung over his Upper East Side penthouse bed since the 1920s. “Stolen the same week the Russians put a dog into space,” someone replaced it with a near-exacting replica perhaps right under Marty’s nose. Events are presented as possible scenarios as to when the heist may have occurred. The counterfeit is so masterful it takes Marty six months to notice it isn’t the real deal, whereupon he hires a private investigator to uncover who probably forged it. It takes Marty another forty years, aged into his eighties, to catch up with the forger.

At first, righting the wrong consumes the victim, who in a different way is as two-faced, artful, and immoral as the perpetrator. Forty-years without his beloved painting and the remorse of his deception doesn’t destroy him but it has taken a big toll. To understand the “existential meaning” of the painting to Marty and Ellie is to understand the man he did not become and the woman she strove to be.

While we can certainly pass judgment on Marty’s and Ellie’s actions, with the benefit of insight I think the overarching point is how much a magnificent piece of art can affect lives. An exhibition about a masterpiece, penned by a master.

Lorraine

Pingback: La vida secreta del arte en The Last Painting of Sara De Vos | Nuestro Rincón de Lectura

My only quibble about this well-written novel is why the title is OF and not BY Sara de Vos?! Readers surely imagine a portrait of her! To me it sounds like a poor translation (in German and French for example there can be ambiguity) but English clearly distinguishes between, say, a drawing OF a chimpanzee and a drawing BY a chimpanzee? The author is a native English speaker, so I’m flummoxed…