SEDUCTION: CREATING A STATE-OF-THE-ART DEPARTMENT STORE, PARIS, END OF THE 19TH CENTURY: Do you wish to read more classics yet keep reaching for contemporary fiction? Are you hooked on Downton Abbey – for its old-world costumes, grand architecture, upstairs-downstairs relationships? Do you appreciate Mad Men – for its nostalgic fashions, fabulous style, portrayal of the shallowness of new-world greed? Émile Zola’s, The Ladies Paradise (original title), written nearly 130 years ago, remarkably satisfies all three. It is remarkable for its lavish prose, and timely message about our culture’s obsession with money.

SEDUCTION: CREATING A STATE-OF-THE-ART DEPARTMENT STORE, PARIS, END OF THE 19TH CENTURY: Do you wish to read more classics yet keep reaching for contemporary fiction? Are you hooked on Downton Abbey – for its old-world costumes, grand architecture, upstairs-downstairs relationships? Do you appreciate Mad Men – for its nostalgic fashions, fabulous style, portrayal of the shallowness of new-world greed? Émile Zola’s, The Ladies Paradise (original title), written nearly 130 years ago, remarkably satisfies all three. It is remarkable for its lavish prose, and timely message about our culture’s obsession with money.

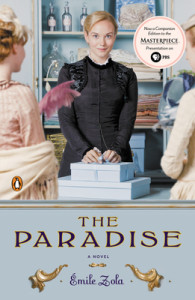

The charming cover of this newly published companion to PBS’ recent Masterpiece Theatre TV adaptation of Zola’s classic French novel caught my eye. It gave me the idea to first read the historical novel, and then watch the seven episodes of Season 1 (available online until 12/17), to see whether the old novel vs. the new visual production wins out. While I’ve only watched the two-hour premiere episode, I already feel hard-pressed to imagine anything beating 438 pages of extravagant prose detailing the “modern realization of a dreamed of palace,” the creation of a “colossal bazaar,” a “cathedral of commerce” where “women reigned supreme.”

The writing builds to a crescendo that matches the intensity of the shopping fever of the women patrons, seduced into buying luxuries they neither need nor can afford, some resorting to thievery, intoxicated by the beauty of fabrics and other merchandise from around the world filling the ever-expanding establishment.

Two characters drive the story:

Octave Mouret – the “governor” – a brilliant businessman from the south of France who “enjoyed a personal pleasure in satisfying other people’s passions” with his big dreams of revolutionizing a drapery business into an opulent department store known all over Paris and the world. He has exciting ideas for creating and organizing departments, displaying goods, renewing merchandise, reducing prices, absorbing returns, to build his empire – a “borrealistic vista” for his “nation of women” shoppers.

And Denise Baudu, a beautiful, sweet, sensitive, and innocent poor shopgirl from the Valognes countryside, caring for her two younger brothers, who works her way up the sales ladder and defies Mouret’s boasting that the “woman who will catch me isn’t born yet.” Hers is not just an endearing rags-to-riches story, but a tale of hardship and endurance and courage to stand up for moral principles.

There are many other characters the reader has to keep track of: Mouret’s right-hand man, Bourdonacle; Denise’s uncle Baudu, whose business, The Old Elbeuf, is depressing against the onslaught of his competition; Bourras, the old umbrella maker who offers Denise scanty accomodations when she leaves those of her employer, for a time; Denise’s good friend, Pauline; Clara, a jealous salesgirl; many lady patrons such as Madames Marty, Robineau, Desforges, Guibal, and Aurelie; other salespeople such as Hutin, Favier, Deloche, whose unrequited love for Denise is painful; and Jouve, the Inspector. None, however, compare to Mouret’s passions and Denise’s resoluteness when Mouret tries to buy her love.

Still, the primary raison d’etre for posting this review is the sumptuous, extraordinary prose that literally overwhelms the reader, just as the merchandise of The Ladies Paradise overwhelms the female shopper. Often, Zola uses the metaphor of water to describe the “steady stream of goods,” the “flood of goods,” the“rising sea” of goods, the “swallowing up.” And oh how he describes his “creations”:

It was at the further end of the hall, around one of the small wrought-iron columns which supported the glass roof, a veritable torrent of stuffs, a puffy sheet falling from above and spreading down to the floor. At first stood out the light stains and tender silks, the satins à la Reine and Renaissance, with the pearly tones of spring water; light silks, transparent as crystals – Nile green, Indian-azure, May-rose, and Danube-blue. Then came the stronger fabrics: marvellous satins, duchess silks, warm tints, rolling in great waves; and right at the bottom, as in a fountain-basin, reposed the heavy stuffs, the figured silks, the damasks, brocades, and lovely silvered silks in the midst of a deep bed of every sort – black, white, and colored – skillfully disposed on silk and satin grounds, hollowing out with their medley of colors a still lake in which the reflex of the sky seemed to be dancing.

The sharp prose also provides Zola a means for Mouret, in one of his “fits of frankness,” to verbalize the growing anti-Semitism of this period in French history. For this is the novelist who some years later penned an essay, “J’Accuse,” referring to the Dreyfus case, in which a Jewish French army officer was wrongly accused of providing secrets to Germany. Zola was later sued by the French army, imprisoned, and eventually fled to England. So, the BBC’s adaptation of his novel to northern England feels right.

I’d love to know which won out for you? Zola’s novel or PBS?

Lorraine