Ties that bind – A family’s fierce loyalty and the history of a place (West Virginia’s Eastern Panhandle, 1938): The truth about The Truth According to Us is that it’s a big novel with a big heart. More truthfully, it beats with many hearts:

Ties that bind – A family’s fierce loyalty and the history of a place (West Virginia’s Eastern Panhandle, 1938): The truth about The Truth According to Us is that it’s a big novel with a big heart. More truthfully, it beats with many hearts:

Two generations of the Romeyn family living under the same roof, a “white-brick and gracious” house with one of those friendly, inviting porches of bygone days. They’re a charming, quirky, irresistible fictional clan. Joined one sultry West Virginia summer in 1938 by a beautiful, sophisticated “princess,” Layla Beck, who boards with them, elegantly stirring their hearts and ours.

The warmth and sparkle of this literary gem invite you right in. Come casual and cool. Marvel at the delightful, versatile prose told in multiple voices. Smile at the family’s eccentricity. Transport yourself to a culture deeply rooted to the history of the Appalachian mountain region in the Eastern Panhandle of the State during the Depression era. Keep your antennae up too, for the complex family dynamics and loyalties that ensue.

While we’re talking truths, let me add mine. This is the same Annie Barrows who co-authored the widely bestselling The Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Pie Society, delivered entirely in the epistolary format. You’ll find those same artful letters here (Layla’s voice). But it’s the other voices, singular and nimble, delivered in chatty, sassy dialogue; in narrative reports (Layla’s again); and through one character’s nagging, painfully loyal conscience that richly develop the characters. (“Character fascinates me – the power of it,” penned Layla.) So, while I liked the Guernsey novel, the truth is I loved this one and bet you will too.

First, the invented locale because the fictional setting, carefully tied to real history, is central: Macedonia, “tucked up in a crook between the Potomac and the Shenandoah,” is a small town steeped in Civil War history where everyone knows (or thinks they know) everyone’s business. Layla stereotyped it as boring, populated by “bumpkins.” Instead, the “tattered, dead-quiet town square” she found was “seething with a white hot passion.” Remember summers here are so hot and humid even “the trees are sweating.”

Time to introduce the unconventional Romeyn bunch. There’s two children, sisters: 12-year-old bookish Willa, our main narrator, and her cuter nine-year-old sister Bird. Willa’s authentic childhood voice is surely due to the writing adventures of the author’s award-winning Ivy and Bean children’s series. (Ivy’s love of reading endures in Willa.) Willa’s parents are divorced, uncommon in the ’30s (about 18% vs. today’s 50%). Felix is their father, Charles Boyer movie-star handsome and elusive. His profession is secretive (something related to chemicals), provoking much curiosity, particularly for Willa, who adores him but can’t bring herself to tell him so. He’s forever mysteriously disappearing, so when the novel opens she’s decided to spy on him to figure things out, but of course that complicates things. Grownups confound her. But the reader suspects the truth is something darker is lurking beneath the delectable antics and gossipy happenings.

Willa tugs at our heart. She longs for her father, wishes “people fussed over” her, sees herself as “puny” and a “pitiful specimen,” rather than the bright, inquisitive, tender child that she is. You’ll want to hug her, but know that she’s selflessly cared for by her surrogate mother, Jottie. At 38, Willa’s attractive yet unmarried aunt is, in these times, considered a spinster. She runs this grand home, also atypical given how hard hit West Virginia was in the Depression. Her “enormous dark eyes” portend her heartaches and loyalties, which you’ll appreciate in her own words and moral code for she’s our second narrator. During the week, this colorful crew includes Jottie’s two sisters, Willa’s aunts. Mae and Minerva are twins. They’re so connected they can’t bear to live without each other even though they’re both married, so they don’t, except on weekends when they return to their husbands and farms. Rounding out this lively tribe is their brother Emmett, Willa’s gentlemanly uncle, an unassuming history teacher who hides behind older brother Felix’s charismatic shadow.

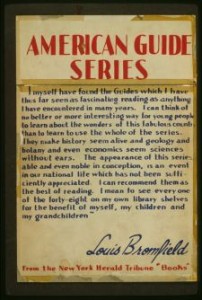

The novel starts off with Willa informing us that Macedonia is celebrating its 150-year history, or “sesquicentennial, a word I thought had to do with fruit for the longest time.” (Fruit growing, especially apples, is prevalent here.) The festivities culminate in September with the unveiling of an historic event, part of FDR’s Federal Writers’ Project, a New Deal Works Progress Administration employment relief program.

Federal Writers’ Project

via Library of Congress

The head of the Project is Layla’s uncle, Ben. She’s not your average candidate. The “black sheep” in her distinguished Washington, DC family, she defied her Senator father’s elitist marital choice, so she was sent away as a favor to write West Virginia’s first State Guide, one of The American Guide Series produced in the ’30s and early ’40s. Macedonia may be only 85 miles from our capital city, but it’s worlds away from the privileged life this 24-year-old stylish lady was accustomed to. With “one-quarter of the employable citizens of this country” out of work, she’s reprimanded about gratitude, but all Layla envisions is a dreadful existence over the summer months of her forced upon assignment.

How could she be miserable, though, with such a memorable family like the Romeyns? The truth is around them “she seemed to glow.” Her letters back home reveal her changing sentiments, as she interviews a long list of the town’s “most illustrious” and tours scenic and historic sites, becoming fervent “to make my little book the best history of Macedonia that ever existed.” Her WPA accounts surprise everyone. Turns out she’s a gifted writer. Of course, the truth is the real gifted writer is Annie Barrows.

Macedonia’s biggest employer is the American Everlasting Hosiery Company, a fitting choice for this part of West Virginia with a history of textile manufacturing. (This is not coal country Layla reminds us, it’s “apple, cow and sock country.”) In its heyday, the mill employed 950 people, meaning “half the town worked in that mill and the other half wished it did.” Hence, the mill fills the novel’s economic heart.

Willa’s deceased grandfather, St. Clair – a great name for he was a “Santa Claus” whose benevolence remains a formidable spirit – was its former President. Still, worker’s rights are a brewing issue, reflecting the rise of the 1930s labor union movement.

Which is to say that the scope of the novel isn’t all charm and nostalgia for milkshakes, ice cream sodas, penny candy, “sweating-cold” Coca Coca bottles, paper dolls, Mom-and-Pop department stores selling “snoods” and “jabots,” although there’s plenty of fun reminiscing. But there’s also penny pinching even among the most influential, entrenched attitudes, and a catastrophic fire in 1920 that burned down the mill, causing the loss of someone dear to this family.

An astute child plays detective searching for “the right ending.” A tragedy that happened 18 years ago still tears apart hearts. When those hearts are pulled together, the ending is the “giant blanket” Willa yearns for to comfort them all. Comforting us too.

Lorraine

Thanks for this wonderful post. You are an excellent writer.

I have this book but haven’t read it yet.

ENJOY your day.

Elizabeth

Silver’s Reviews

My Blog

Hi Elizabeth,

I read your blog’s profile: I love meeting book blogger’s too! Like you, I love historical fiction, and was so impressed with how Annie Barrows’ crafted her novel without hitting you over the head with facts but sprinkling in so many. It hooks you from the first sentence. Thanks for commenting. Hope you get time to read it soon. Lorraine