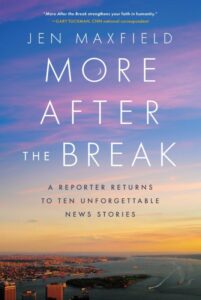

What happens to traumatized people years after their catastrophic stories were reported on TV news? (NJ/NYC beat & New Orleans; 2000 to 2021): More After The Break reads like a riveting and emotionally stirring collection of short stories. Except these stories are so real you wish they were fiction.

Of the “ten thousand” people Emmy-award winning journalist Jen Maxfield interviewed for TV, chosen from “four thousand stories” spanning twenty-two years, ten are revisited in this compassionate, groundbreaking book. Each breathtaking, and delicate in reaching out to people she’d been thrown-together with amidst horrific circumstances.

How many reporters dare to re-open doors not knowing what “chaos and sadness” they might be stepping back into? “We dip our toes in the pool of your grief but never jump in for fear of drowning.”

Maxfield’s commitment to the highest ideals of journalism shines, so it’s not surprising she now teaches broadcast journalism at her alma mater, Columbia University’s Graduate School of Journalism. Keenly aware the afflicted person at the center of the story always comes first, despite the rush to get the story, the author’s warmth, honesty, respectfulness, and graciousness offers comfort to the darkness. Humbly though, she asks: “What can I offer”? Answering with, “The space to tell their story.”

Tracking down people met in crisis years ago is the easy part thanks to technology she says, but there’s nothing easy about these stories. The reward, which the reader perceives, is that she “could not have predicted how much these reunions would enrich my life with joy and optimism.”

Maxfield’s gratitude is also refreshing. Grateful for the extraordinary “emotional intimacy within minutes” granted whenever interviewing/intruding on someone in his/her most vulnerable, naked state; the cameramen (no female photographers in these stories) who stood beside her so she never felt “alone”; and being cocooned in the “live truck” with her crew preparing to transition from reality into the surreal.

How does a journalist find balance in their life stepping outside their world to the unknown abyss? For Maxfield that means getting the urgent call, having to drop everything to race out the door, leaving her family – husband and three children, young during her coverage of these stories – to be consumed by nightmare stories working up to sixteen hours a day. These ten stories are staggering in terms of human trauma, which makes the idea for and realization of this book high-stakes and notable.

More After The Break comes at a crucial time when the public’s trust in the media has reached alarmingly low rates. If only wide readership of this book could reverse the trend, by witnessing serious journalists/reporters/anchors do their upmost to maintain the principles and ethics of the Fourth Estate.

Maxfield wonders whether the people she contacts will even remember her. Although trauma can wipe out memories, we understand why no one forgets the genuinely empathetic newswoman.

Having cut her teeth at two local upstate New York TV stations, Maxfield worked at Eyewitness News on ABC7 New York for ten years; since 2013 she’s covered the news for NBC4New York. Her real start she describes came in graduate school, making a documentary for her thesis. This story saved for the last, perhaps to sum up two decades worth of lessons learned.

Bergen County, New Jersey is the author’s home. So while she covers local and NYC news stories, one is included reliving being called upon to cover Hurricane Katrina a day after it devastated Louisiana and the Mississippi Gulf Coast. Twenty-eight at the time, it was the most “high profiled” and “massive” story of her career. It shatters any notions you might have that TV news reporting during catastrophes is to be envied. Lives are reduced to the absolute minimum of basic needs – drinking water, coffee, bathrooms, and gas for the vehicle. Still, enviable compared to the disaster.

“TV news reporting is not a glamourous job, but its purpose is lofty. Spotlighting the people who represent the best in human nature helps our viewers see beyond the despair of the situation, and it gives us all hope.”

Perhaps another journalist could have written this book as beautifully. But not with the same sensitive and compassionate prose reflecting Maxfield’s laudatory approach to her profession.

We don’t know the people in these stories. Nor the disasters that hit them, with the exception of Hurricane Katrina and perhaps the “60,000-pound ferry” that crashed into a Staten Island pier. “Angel on the Ferry” opens the collection, maybe because it’s the most awe-inspiring, though there’s plenty of competition. The victim interviewed was twenty-four at the time, a NYC waiter who didn’t earn much money on his way home. Also interviewed was the heroine nurse who saved his life, opportunely vacationing from Wales. Could Maxfield have been as courageous? she reflects. It does take a different type of courage to re-enter Paul Esposito’s life, not knowing what kind of physical and mental condition she’d find him in after losing both of his legs. His words and mental attitude, like the book’s title, are unforgettable. “The ferry crash was the start of a new chapter” he says, in which he “takes nothing for granted and savors the beauty of every day.” Is this the definition of Grace?

“A Daughter’s Love” is a survival story on two fronts that will take your breath away. How did Tamika Tompkins, a twenty-four-year-old mother of two, one a newborn, survive being stabbed twenty-seven-times (!) by her ex-boyfriend? Wait, there’s more! How did her two-year-old daughter have the wherewithal to jump on top of her bleeding mother stopping her from bleeding to death? Stunning what even the very youngest of children are capable of. A stark warning that adults need to pay closer attention to what they say and how they behave in front of their impressionable kids who hear and observe far more than they’re given credit for.

The “Friday Night” story about a twenty-three-year-old animal lover Tiffany is achingly sad. Her life cut short by an intoxicated hit-and-run driver while she was trying to save a dog lying in the street also hit by a car. Sadness turns to outrage when we learn how just justice is. If the perpetrator had moral convictions – stayed at the scene of the crime as legally required – a jury would likely have found him drunk and guilty, imprisoned for maybe as much as twenty years (NJ law). But who can prove how much alcohol is in your system when you’ve run away? Seven years in jail for erasing a life is an indignation, but what do you call getting out of prison on parole in six months?

Obviously, there’s more stories in this moving collection. Each strike at the randomness and fairness of life. And, how some people do care deeply about that.

Lorraine