Searingly honest memoir about defying the obstacles (New York City, 2004 to present, and other cities in the US, Australia, Japan; backstory Northern VA): If “the most compelling stories are the ones about people on a quest complicated by impossible obstacles” (see Resilience, Courage, and Hope – Getting Through Hard Times), then by that standard alone, David Chang’s memoir Eat a Peach is “most compelling.”

Chang is a world renowned, break-the-mold chef who founded the Momofuku “Asian-influenced egalitarian” restaurant chain that defies categorization. Innovative dishes that mix Asian and non-Asian (Italian, Mexican) foods, so please don’t call his cuisine Asian-fusion, he says. One of many things Chang takes pains to make sure we know – culinary and more broadly about the challenges of being Korean American, and someone dealing with manic-depression.

Chang is the real deal. Not what you might expect from a forty-two year old man who created an Empire, making his memoir different than you might expect. A give-it-all-you’ve-got and then some spirit breaking expectations and stereotypes, reflecting the same gusto he gives to his craft.

In 2004, Chang opened his first Momofuku restaurant: a Noodle Bar in the East Village in Manhattan with minimalist décor but high energy, cooking in front of diners, creating dishes with smells and tastes people never smelled or tasted before. As Chang tells it, there was nothing like it before.

So you might expect that the winner of the most coveted cooking awards in the world – James Beard, Michelin, World’s 50 Best Restaurants – a man named by Esquire as “one of the most influential people of the 21st century”, along with Time magazine calling him one of the 100 Most Influential People in the World – would be full-of-himself. Yet Chang does everything he can to try to convince us he doesn’t deserve the success he’s achieved. Commendable that he wants to express how much he owes to his extraordinarily talented and loyal staff. But it’s not due to modesty. It’s incredible honesty.

Over and over, he tells us that he’s not the man you think he is. That he got to where he is on a fluke. Cooking was the one thing he “didn’t hate doing,” nor failed at. No matter how hard he tries – and he tries harder than most – he ends up showing us why he deserves the accolades. Compelling, because he seems like one of the most honest people in the world.

David Chang has traveled the world, to “gather from everywhere.” “I wanted to know why people liked what they liked.” His first trip was to Japan, eye-opening as it inspired the idea of preparing food for everyone to see, then used “the dining room as a classroom” to observe whether they liked what they ate. Borrowing and adapting is why he says his cuisine is not “authentic.” At least he agrees that what he ends up serving is one-of-a-kind, but for someone whose gone as far as opening a “culinary lab” in NYC to experiment with ingredients like a scientist, he doesn’t give himself enough credit for never resting on his laurels.

The more self-effacing, the more the author sounds like someone suffering from Impostor Syndrome. No, he believes he’s suffering “survivor’s guilt.”

Surviving a childhood marked by failures in school, bright but not bright enough for one of the nation’s top-ranked high schools in Northern Virginia where he grew up. Surviving the negative impact of “tiger parenting,” he wants us to know not all Asians are academic powerhouses.

Chang is, though, a powerhouse. An ultra-perfectionist, he made himself into one.

Eat a Peach isn’t singularly focused on the culinary arts, which in his case relies on vision, leadership, teamwork, unrelenting eighteen-hour work days, with encyclopedic knowledge of the history of great chefs and what makes a great chef. (An Appendix, 33 Rules for Becoming a Chef, earnestly boils down “usable” advice.) He’s also well-read outside culinary circles, so you’ll also get a flood of philosophical thoughts, and “various cultural truths” about Korean-Americans, most of which he doesn’t agree with. He recognizes that what he has to say about his culture may be offensive, but it fits with his fierce honesty.

Chang does believe in a “Korean emotion” called han, which he describes as:

“some combination of strife or unease, sadness, and resentment, born from the many historical injustices and indignities endured by our people. It’s a term that came into use after the Japanese occupation of Korea, and it describes this characteristic sorrowness and bitterness that Koreans seem to possess wherever they are in the world. It is transmitted from generation to generation and defines much of the art, literature, and cinema that comes out of Korean culture.”

Chang is an eloquent and thoughtful writer. It would be remiss, then, not to point out he’s also a frequent user of profanity. He knows it, and works to tone down his anger. How can someone be so angry having achieved so much?

Chang is intense. He feels injustices, suffers deeply. Complex emotions, like his complex cuisine. Emotions – “my personal brand of rage” – are key to his success. “I think the job – the fear, the stress, the habits I’d learned, the culture – unlocked what was already inside me.”

That’s the tip of the iceberg. Chang was diagnosed with bipolar disorder. (Clinical depression zaps your energy so badly you can’t even get out of bed, yet Chang is the definition of a workaholic.) His editor wanted him to avoid discussing it, reminding us mental illness is still a stigma. That’s not who Chang is, so he tells us right from the get-go.

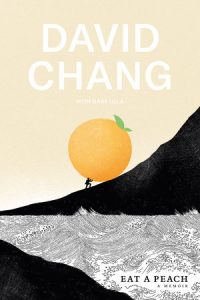

In a striking and seductive Prologue, he uses an interesting and effective vehicle for introducing himself in five pages. It’s a behind-the-scenes look at the memoir’s editorial process. The cover design is described in detail, with images, as to what went behind it. He did not want his picture on the cover, nor draw attention to his name. Printed in pale white, we focus on how he perceives himself as a tiny man in the universe pushing a gigantic peach up a mountain, conjuring the image of Sisyphus in Greek mythology. The peach is also significant, as the meaning of Momofuku in Japanese is “juicy peach.”

Not a tiny life, that’s for sure. Besides his numerous, wildly successful restaurants around the globe, he’s authored two bestselling cookbooks and created a Netflix documentary series called Ugly Delicious that fans anxiously await news it’s been renewed for a third season.

After surviving some do-or-die restaurant experiences, he came up with the idea of a daily email system with his staff – The Roundtable. We’re treated to many examples of how everyone was brought into the loop on every detail no matter how small or “crazy;” how much he encouraged new ideas; what it means to lead regardless of the obstacles; how magical it feels when it all comes together; and how beautiful it is when a leader treats his team like family.

David Chang may sound like someone who doesn’t like himself all that much, but we do. We like his tell-it-like-it-feels prose, full of his inventiveness, perseverance, and yes, authenticity, wanting to be the best he can be.

How will COVID-19 affect his restaurants? He’s closed two, but he’s a survivor with tremendous creativity. The memoir makes us feel he’ll climb these new, formidable mountains, help lead the way.

Lorraine