Unbearable losses, and the fight to get what’s yours back (Jamaica and Brooklyn, 1990s – 2010s): Tea by the Sea might be one of your favorite feminist novels of the year. Surely Jamaican-born Plum Valentine, the protagonist, will capture your heart as she’s “focused on mattering, on not being a person so easily discarded and left behind.”

Plum has been a victim of not having “agency” in her life. Lacking control and the freedom to choose her destiny, others made dreadful decisions that predetermined her life, leaving her behind. Her childhood was marked by strict parental control that ripped her away from her beloved Jamaican homeland to an immigrant’s life in Prospect Park, Brooklyn, where she did not belong. Twice they re-shuffled her from Jamaica to Brooklyn and back, abandoning her again and again. At seventeen, she suffered “the most greatest loss” of all: the day after she gave birth to a baby girl in a Jamaican hospital her daughter was carried away by the father, Lenworth, without letting anyone know their whereabouts. Plum had planned to name her Marissa, which in Spanish means the sea and signified the “promise and freedom” she never had.

For seventeen years – “6,205 days give or take a few for leap years” to be exact – she searched from Jamaica and Brooklyn for the daughter whose father told her she was “left behind” by her mother, telling everyone else she’d died. For Plum, that’s seventeen years of “calcified grief”; for her daughter, you’ll wonder what she believed.

Debut author Donna Hemans has written a stirring story that deserves the important Jamaican literary prize she was awarded by the Jamaican Writers Society. It also deserves national attention, tackling the complexity of human emotions, raising a fundamental question about what matters most to live a good life, asking moral questions about motivations and terribly misguided decisions. The eloquent, atmospheric prose also reveals little-known black history at an historical time when America is demanding its racist history be better known. While this is not a novel focused on social justice, it is embedded in its laser-focus on seeking justice for one mother and her daughter.

The Una Marson Award honors a leading Jamaican activist and poet who advocated for Caribbean literature. Another Jamaican poet and activist, apparently legendary, Louise Bennett-Coverly, was celebrated last year on her 100th birthday with a petition (it failed) to recognize a second official language in Jamaica, called “patois,” besides English. She’s credited with raising the dialogue of the Jamaica folk to an art level. Plum’s story is activism in a deeply personal way.

The use of patois is a feature of Jamaican literature. Hemans’ writing mingles the two ways of speaking artfully. English is the more common, but the local dialect is authentically expressed, flavored with dialogue like this: “One day him come back wid hur,” and “Mi dear, you nuh have to ask.”

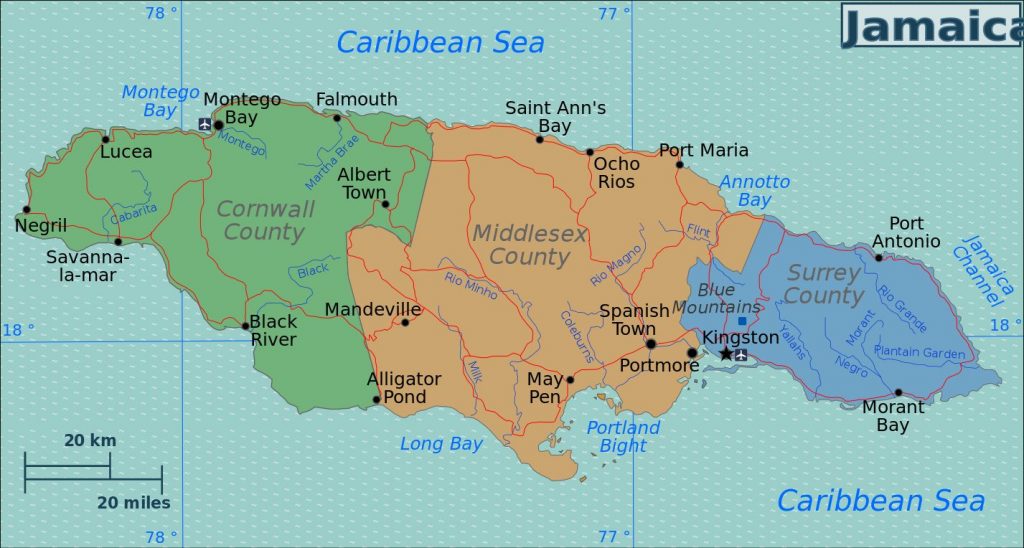

Judge Tea by the Sea by its exquisite cover! Which establishes Plum’s love of the sparking blue waters of the Caribbean Sea and the powdery white sandy beaches encircling Jamaica, a large tropical island south of Cuba, part of the West Indies that become a country when it achieved independence from British colonial rule in 1962.

Plum’s major obstacle to finding her daughter is finding the father who kidnapped her, proving incredibly difficult as he reinvents his life twice, and never looked back. He named their daughter Opal, because her almond-shaped, topaz eyes reminded him of a jewel. Eyes that were also a constant reminder of Plum as they were the same. So was their skin, darker than his.

Will Plum find her daughter? That’s the central question propelling gripping storytelling.

The freeing sea is symbolic of the searching plot to set oneself free, by taking a stand for what’s morally right, despite the consequences. When the novel ends, Plum is thirty-four and while her emotional life feels “suspended” and “fossilized” she has moved on. The floating sea also personifies the “unending” push and pull of Plum’s changing life.

The prose ebbs and flows too. Offsetting the almost indescribable pain of unrelenting grief, which the author has found heart-stopping words for, are lovely descriptions of Jamaica’s colorful setting – “Spanish style” and “plantation” architectural types, abundance and diversity of flowers and trees, spicy cuisine. Yet the beauty is pierced by Plum’s raw pain, and the island’s racial history. So the prose goes from feeling like a calming summer breeze to intense yearning and suspenseful searching that never fades.

Interestingly, the timeline also floats, moving back and forth without being specified until the end, seeming to emphasize the timelessness of a mother’s grief and the longing for the mother a girl never knew. Except for one date, the only date that really matters: September 16th when Marissa/Opal was born.

The geography spans Jamaica from its western coast to east, but is mostly set in small, rural towns on the northwestern side, near Montego and Discovery Bays.

Montego Bay:

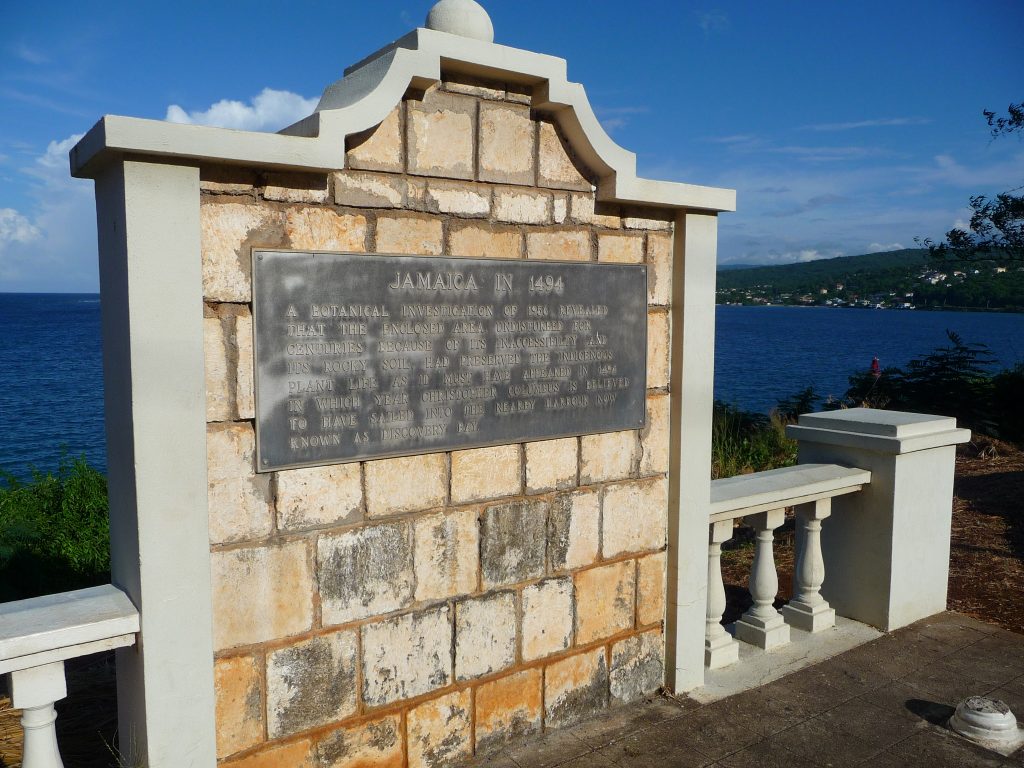

On Discovery Bay a plaque commemorates Columbus’ sailing into the bay in 1494:

The Columbus history is important for another reason: “the Tainos, a group long extinct from Jamaica, decimated by hard labor and the diseases brought to the island by Christopher Columbus and the cohort of explorers, diseases for which their bodies had built no immunity.” Once we may have dismissed epic diseases as ancient history, but today we know better, living in a moment when history feels like it’s repeating itself. Erasing Jamaica’s indigenous people also reminds us of America’s shameful history towards Native Americans. Jamaica is also another country with a legacy of slave history.

The varied settings let us imagine Jamaica, and take us through the different places Plum lived during her formative and later years; also to an abandoned house Lenworth first took Opal to. He grew up in a poor, rural village near the eastern side; a built-up Kingston on the eastern coast is one of the areas Plum searched.

Part I is aptly titled Unforgettable, and Forgettable. Plum’s loss is unforgettable since she’s been tossed aside so many times she feels forgettable. Except to Opal, who senses her mother’s gone as an infant unable to be soothed by one of two substitute mothers, and then at four when she expresses the missing piece of herself asking: “How come I don’t have a mother?”

While you want to abhor Lenworth, your feelings about him are not black-or-white. Hemans has created a nuanced character whose motives and childhood influences give us insight. Still, the tragedy that ensued was a doomed decision he regretted the rest of his life, but didn’t do anything about except do everything in his power to hide by carefully controlling his life. Power, or the lack of it, is a driving force and theme.

Of course Lenworth knows he committed a crime, actually two. First when he was twenty-three and and Plum got pregnant under-age at sixteen. He was also her tutor at her boarding school (a throwback to British rule) so he’d crossed the line professionally as well. The second crime, the kidnapping. The tragedy is seen on multiple fronts. Plum and Opal are not the only ones who’ve suffered, he has too. But our sympathies are always with Plum and Opal, who we know little about, as this is Plum’s story, told through Plum’s mournful soul.

A brutally emotional story, yet it’s painted with beauty, resilience, and so much determination it makes Plum the unforgettable person she fought so hard to be.

Lorraine