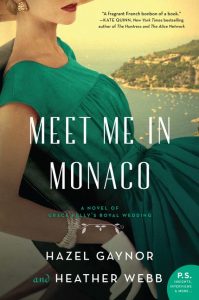

The dangers of love during an unfamiliar slice of French WWII history (South of France, February – September 1943; England and France, 1993): Laura Madeleine has found her secret to writing elegant, heartfelt novels set in France. The Secrets Between Us her third. (Her prior novel reviewed here.) It’ll be interesting to see what she comes up with in Spain, the setting of her soon-to-be-released fourth novel, An Echo of Scandal.

A few of the author’s secrets seem knowable; the rest, the magic of writing. As a former baker who still creates her own recipes, one ingredient she employs is her passion for baking. A French village bakery centers the WWII storyline, producing “life-giving dough” amidst the despair. Fifty years later, a second plotline intersects with it.

Two female protagonists narrate: 1943 eighteen-year-old Ceci, baker-assistant to her father, and 1993 twenty-something Annie, an archivist living in England. It doesn’t take long for their connection to become evident.

The war story is set in a fictional mountain village, Saint-Antoine about forty miles north of the French Riviera. It’s inspired by the historically significant one, Saint-Martin-Vésubie.

In January 1943, a month before the novel opens, the anti-Semitic French Vichy government established its Gestalpo equivalent military force – the milice – to go after members of the French Resistance risking their lives to save Jews. In February, the novel begins, timed to when Jewish refugees were rounded up and sent to the village occupied by the Italians not the Germans until September 1943, the month the war story ends, when the Germans took over. An example of fine research blended into exceptional fiction.

The real town’s non-Jewish residents were honored by the World Holocaust Center Yad Vashem, with the designation Righteous Among Nations for what they did to protect the Jewish people. These courageous acts are inspiring and bring a slice of lightness to the inhumane Holocaust darkness. Made more compelling when we learn about the Italians’ role in WWII – historical fiction not often seen.

By Eric Gaba for original blank, mapRama for zones [CC BY-SA 4.0]

Many secrets run through the novel, not just the dangerous ones in the title.

Generations of family, particularly grandmothers, are key to the two narratives. Another ingredient the author mixes in, surely adding emotion to the writing as the author’s grandmother’s WWII stories in France inspired the novel. (See her post, which includes photos of the historic village.) The author’s family lives in France; today she lives in England. Much like Annie, who travels from England to France, in search of her long-lost grandmother at the urging of her famous anthropologist mother.

Annie grew up without knowing who her father was. Her grandmother Celeste helped raise her when her single mother was off traveling. Still, she’s reluctant to pick up and leave her new history-documenting job outside of London, having just returned to her workplace after an unexplained absence. Miserable in her new position, a “demotion” in her eyes. Computer cataloging historical documents isn’t intimate like thumbing through personal, handwritten artifacts. Annie’s kept it a secret why she had to take leave, a sign she’s an extremely private person, much like Ceci. Two different women decades apart, but they share loneliness and compassion for others, resulting in both choosing uncharacteristic paths.

Annie abides by her mother’s wishes partly because she’s worried her cancer surgery means she’s running out of time to make amends with her mother Celeste, whom she hasn’t heard from in years. Annie doesn’t know what happened between them, nor, ironically, the details of her own family’s history – the other reason she can’t turn away.

With access to historical information, Annie’s personal research takes off quickly. As Ceci’s and Celeste’s stories converge, chapters increasingly flow seamlessly into one another, letting the years conflate, letting the past merge into the present. Rightfully so: burying far-reaching secrets persists and torments.

Generations also drive the labor-of-love performed at the bakery, owned by four generations of Ceci’s family her father inherited. Five years ago, times were better, but during the war even basic ingredients were hard and dicey to acquire. The bread barely edible, nothing like the savory and decadent taste it once was. (Think chocolate stuffed into quintessential French dough.)

Ceci and her father rose at 4 am, baked until 11, then began selling, now to a long-line of starving Jews who’d lost everything when they were forced into the stone mountain village. Ceci’s childhood best friend, Paul, who grows more fond of her by the day, assists too when he’s not off playing his hidden role in the war.

Ceci, and the other villagers, are poor. A hotel, with its friendly managers, is the bakery’s major source of income. Then it becomes vital to the refugees, and shows up in the wow ending. The villagers rent out rooms; Ceci’s bedroom over the bakery rented to a Jewish couple. She shared it with her brother, now an imprisoned soldier gone missing. Ceci moved in with her grandmother, but the bakery is where you’ll usually find her.

The Jewish boarders in her house escaped from Belgium, Myriam and Daniel Reiss. Ceci realizes they’re well-off, so why didn’t they pay someone to falsify their identity papers so they weren’t stamped J, to avoid the round-up? What have they done? Seen? Heard? And why is Daniel gone most of the day, leaving Myriam alone?

He says she’s a writer and fragile, but that doesn’t quite mesh with her inconsistent behavior. For days on end, Myriam holes herself up in Ceci’s bedroom where if she’s writing she’s also crying. But then Ceci spots her laughing, drinking, smoking at the town’s café. Ceci is watchful, then confused by a subtle look on Myriam’s face, which turns into a fixation on what’s up with beautiful Myriam.

Ceci is the character who palpably feels the anguish of the refugees. The Italians protected the Jews as best as they could. Who knew this aspect of the war?

When the milice arrive, we brace for what will happen. The author doesn’t want to hit us with graphic violence. One scene she touches on it, others allude to it, but her technique is to grab us emotionally with lyrical, merciful prose.

From beginning to the end, the novel captures us, starting with the opening quote: “There is bread and salt between us.” Defined as “an Arabic saying expressing an alliance, a bond, an oath not to be broken.” In this novel, a hopeless bond.

A Prologue refers to the Bible, to Lot’s wife “who was turned into a pillar of salt for looking back.” Precisely what the novel does. Salt also refers to the ancient salt trading roads; the old path winds its way into the steep mountains surrounding the village. And, of course, a pinch of salt is essential to bread.

Ceci notices other refugees, like three boys who lead us to imagine the unimaginable as fewer Jewish children survived the Holocaust than adults. These children don’t even know what happened to their parents. Compared to their trauma and plight, Ceci doesn’t feel sorry for herself. It’s impossible not to want to hug Ceci.

Ceci never spoke about the war, like everyone from that greatest generation. Maybe that’s why there’s such an appetite for WWII fiction. For the sacrifices made for country, survival, freedom, human rights, and for the desperation of tender wartime love never forgotten. Baker-turned novelist Laura Madeleine knows how to feed that appetite.

Lorraine