Weaving magic into a staggering story of enslavement (North Carolina and New Orleans, West Africa spiritually; 1800s before the Civil War): Can literature set us free?

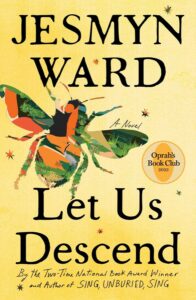

“Let us descend into the blind world” could have been penned by poetic, literary genius Jesmyn Ward. But it comes from Dante’s epic 14th century poem, Inferno, inspiring the title and hellish journey depicted in Ward’s new historical novel, Let Us Descend. Of epic proportions.

An NPR story, Remembering New Orleans’ Overlooked Ties to Slavery, inspired the setting and ethos of 19th century slavery, centered at the virulent hotbed of America’s slave market in New Orleans.

“Grief and sorrow” are embedded into this deeply felt story told by a teenage narrator, Annis. It’s Ward’s grief and sorrow too. For her brother, ancestors, community, while composed in the rawness of tremendous personal loss: her husband suddenly died right before COVID had a public name. While millions were grieving too.

What happens when you’re hit with so many unbearable losses? Ward contemplated stopping writing. We’re grateful she found a way to pour her emotions into an intense story aimed at engendering empathy.

Ward’s intention isn’t to focus on historical details. Rather, on the history of a culture that dehumanized black people, women the focus, in every way possible.

We know that even before we open the pages. The exceptionally moving book cover isn’t the typical image. Let Us Descend rightfully draws from Ward’s affecting words, printed like a poem, excerpted from an interview with former President Barack Obama in Vanity Fair. On the front cover, Ward beckons us:

“Sit with me.

Let me tell you a story . . .

It feels as if I have been in the dark,

journeying with this character,

for a long time.

“It is difficult to walk south with Annis.

Her narrative descends from one

hellscape to another,

but I promise that if you come

with me, you will rise.

It will be worth the work,

worth the walking.”

Those words depict how the words inside move us.

Quoted on the back cover is Ward’s writerly purpose: to “get readers to feel with and feel for the people I’m writing about.” The former president understood what she was after: “The power of empathy . . . that we need to “see somebody’s backstory” or else “we end up reinforcing our prejudices, our biases, our fears.”

Let Us Descend is powerful, but can it change deep-rooted hatred? Can any book, or volumes of books, have that kind of power?

Ward is one of those exceptional writers who can take us further than we’ve been. Far deeper into darkness, far longer than we care to go. If you’ve read any of her work, such as her 2017 Sing, Unburied, Sing, recognized for the second time for the National Book Award, you still remember those ghosts of Mississippi and trust she’ll lead us into the light. Don’t expect that, though, to happen soon. To tell truths based on history she can’t.

The otherworldly spirits in this novel expand to many more. They stretch us.

These spirits are a way of transcending being “owned” and “bound” to earth’s inhumanity, to be unbound by a spiritual world. But not all the spirits are good. Some are evil. Annis must learn to tell the difference. How do you when they set traps? How do we learn whom to trust?

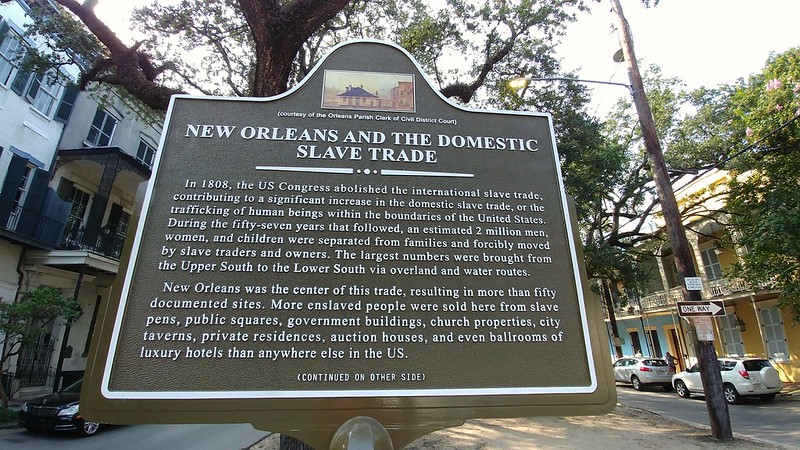

When life on earth descends so brutally, when Annis descends alone from the Upper South to the Deep South, the spirits arrive. Historically, this movement reflects what happened after 1808 when America banned bringing anymore slaves into our country, like Annis’ grandmother Aza who came over from West Africa. Aza was one of hundreds of thousands of slaves raped on our shores. Aza’s Mama is the product of that violence. Annis, from the rape of her Mama.

Aza’s true spirit stands out from the rest. She’s the one Annis and her Mama trust seeking to protect. She’s the kind of fighting spirit that strengthens them both. Annis’ mother is called a “warrior,” teaching Annis some of the fundamentals of how to fight, or not – “a part of fighting too” – when they find fleeting moments to flee into the woods.

The other spirits that flow through this extraordinarily soulful novel appear when Annis is desperate to free herself from the “unbearable same.” These spirits have many symbolic meanings – biblical, mythological, cultural, psychological, literary. Some are named like the Wind Spirit, Water, Those Who Foretell, Those Who Take and Give, She Who Remembers. Some we understand, others we guess at.

Opening when Annis and her Mama are slaves on a rice plantation in North Carolina. They don’t call the plantation owner master. He’s only the “sire” – sired like animals. Ward shows us she’s a master of finding words that tug at our hearts. Reaching down to find the right word that calls out penetrating, harsh truths.

On earth, Annis’ story becomes more hellish, taking her on a long, burning, rope-chained walk. The walk she imagines Annis taking. The walk her Mama likely took. It winds south through the sweltering heat, drowning rivers, dark infested swamps from the North Carolina plantation to a Louisiana sugarcane one. In front and back of Annis, tied to a rope that “eats” at her skin, are women she doesn’t know, nor want to. It’s on this harrowing, death-defying walk that Annis learns “what it means to be alone.” “To know only grief in this new world.”

We can wish all we want for only the benevolent spirits to descend onto Annis’ starved life. Starving for tenderness and touch, from brutality and literally a paucity of food. But that wouldn’t be telling hard truths either.

Annis surpasses any humane concept of vulnerability. Yet there’s something about her that also surpasses our concept of resilience.

Hers is a life that, “ain’t living.” “Everywhere, hot knives of pain. When: “There is no one to carry us back.” That’s told: “Tell them who you are. You more than laying on your back.”

Annis, though, tells herself: “I tried to remember that I still had plenty inside he couldn’t take.” And also told be a wise plantation cook: “Most people can’t see all the layers in a person, just like they can’t taste all that goes into a pot.” “You got to know the taste of what heals you.”

Ward’s prose sears and soars. By the time we understand to “fight for it all” also means know what you’re fighting for, we feel the weight of lost love and kindness. Memories can though, eventually, be a propelling force.

But to rise you must first descend. Count on these “farseeing women” to help us ascend.

Lorraine