Ghostly memories of love and war (Yuehu village, southeast China, 1943-1945; told 70 years later): A Single Swallow is only the second of nine novels by acclaimed Chinese-born author Zhang Ling1 translated into English. Translations represent only 3% of the total American market. The American Literary Translation Association’s database shows Amazon Crossing publishes the lion’s share, along with mostly Independent Publishers and a few imprints of the major publishing houses? Why so few?

Best answered by experts within the publishing industry, but from this reviewer’s experience the simple answer is whether a book is accessible, or not. This year, I identified one book, translated from Swedish, to rave about, but gave up on translated books from Poland, Japan, Brazil, Colombia, Ukraine, and Turkey, finding them too difficult to read. So it’s with great pleasure to introduce Ling’s accessible, lyrical, and unusual historical fiction offering a rare look inside a top secret mission when America and China worked together after Japan invaded China.

Told through the voices of three men, two American and one Chinese, who love the same young Chinese woman, the novel is unique for both historical and literary reasons. The two woven together powerfully.

The forcefulness lies in the stark contrast between writing so affectingly about two extreme circumstances and emotions: the brutality of war “during strange times, when half the world was on fire” versus the beauty of three men loving a courageous yet fragile, stoic, resilient young woman who’s been the victim of unspeakable horrors and hardships. Written with such eloquence, although reading about the horrors of war is not easy to read. But not because we’re not able to understand the meaning of the translated prose.

Ah Yan is the woman at the center of the novel. Her name means Swallow in Chinese. Swallow is a perfect name for her as she’s so thin, bony, and small she seems bird-like. She privately bears her grief and sorrow, but over the course of the novel we see her strength, “compassion, intuition, and calmness under stress,” and the extraordinary lengths she goes to care for others. That in order “to save herself,” she had to first learn how to become someone “saving others.”

The three men’s voices show “three sides of her person,” alternating in chapters. What’s also unusual is we never hear her voice directly. We don’t often read novels told second-hand, through the second person point of view. Without hearing her side, we don’t have the full story, which we assume is intentional. She’s real but not fully within our grasp.

This dream-like quality to Ah Yan fits the surreal use of magical realism for delivering the men’s stories about her and the war. That’s not such an easy thing to pull off either. Since “the memory of war isn’t the same as the war itself,” mixing reality with the otherworldly is an effective way to make their stories, and hers, feel ghostly as the ghosts of war haunt lives forever.

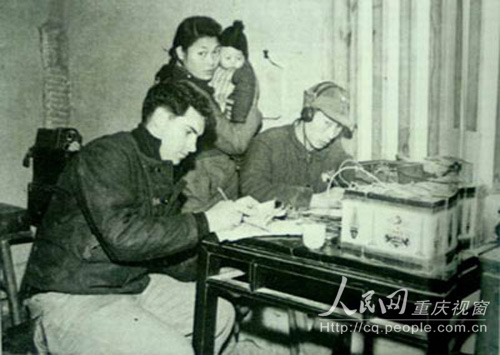

The Sino-American Cooperative Agreement (SACO) established a “high-intensity,” US Navy training camp in an impoverished and secluded village near the southeastern coast of China, which is where the novel takes place.

via Wikimedia Commons

Yuhu was the name of the historical village the author calls Yuehu. “Surrounded by mountains, making it less likely to be attacked, but was still one hundred miles from the area of the Japanese occupation and the sea, putting it within marching distance.” That long distance, combined with a formidable terrain, is where “Americans learned the real meaning of the word ‘walking,’” which they could not have done without the assistance of the Chinese, who knew the land. The primary purpose of the military operation was spying, intelligence gathering, and collecting other information on the enemy, not hand-to-hand combat, but there’s one devastating military incident that’s dramatically described as if the author had been there herself. This scene alone speaks to the veracity of Ling’s research, which included visiting the site and speaking with three Chinese men who’d been part of SACO.

The three fictional male characters all heard the surrender speech of the Emperor of Japan on the radio in 1945 that ended the war, known as the Jewel Voice Broadcast. Before they said their goodbyes, they vowed to annually visit this indelible place of memories after they passed away. Which is why we hear their voices seven decades later.

Each loved Ah Yan differently, so each called her a different name:

Pastor Billy: A US missionary also practicing medicine. He bears witness to Ah Yan’s saving, healing, and maturity “that would’ve taken decades during peacetime.” A fatherly figure twenty years old than Ah Yan, whom he meets when she’s nineteen, he calls her Stella, which he explains “means star,” envisioning her future will shine so she’ll no longer have anything to fear. It will become painfully clear to the reader what crime against her humanity was inflicted on her. To make sure her future will be safer, he teaches her basic medical skills that she soaks up like a sponge, so when the war is over and she’ll have to return to her village she’ll be respected and needed in her community rather than shunned upon. An example of helping us understand a different culture’s traditional norms.

Ian Ferguson: A military training instructor from Chicago, his job is Gunner’s Mate, because he teaches combat skills. We understand a lot about what he does and how the war is going through evocative letters he writes to his mother and other family. The letters are provided via the US Naval archives, which makes the fiction feel real, especially since his fictional commander, Commander Miles, was a real historical figure. His full name was Milton Edward Miles. Even the Commander’s dog, the author calls Ghost, makes his way into his story. Ian called Ah Yan Wende, which means wind in English. To him, she’s “perfection in the moment,” equating her with “the power of the wind, its freedom and its rage.”

Liu Zhaohu, code name 635: From the same village as Ah Yan, Sishiyi Bu, he calls her by her given name. Their fathers are brothers; his father works for her father’s tea plantation. He became a soldier to save China from the Japanese. “Patriotism is born in the mind, a few steps from the heart, but was not yet a heart-wrenching pain,” he says, an example of how the prose of a wartime novel can be poetic. Ferguson is his teacher.

The novel could have still been inaccessible to American audiences if the translation wasn’t as superb as it is. Ling deserves all the credit for communicating the universal language of love and war, but credit is also due to Shelly Bryant, the translator, based on how vividly and movingly the novel reads. Bryant is an Oklahoma native who lives in Shanghai and Singapore, nominated for several translation prizes. She’s also a writer of novels, short stories, and poetry.

The brief Epilogue is brilliant, intensifying the feeling of whether this is a piece of history, or fictional? Together, a stirring, secreted piece of American-Chinese WWII history showing us that “facing death is a form of bravery, but so is facing life.”

Lorraine

1 Zhang Ling lives in Toronto, Canada, but was in Wenzhou, China during the COVID-19 lockdown. The subject of her next book, a work of non-fiction.