Stardom and the heavy price paid (Dublin, also London and Hollywood, 1940s-80s; told in 2010s reflections, Bray, east coast of Ireland): What makes a great female movie star? What is the toll it takes on an “outlandishly interesting,” unorthodox Irish actress of theater and film fame? Similarly, on her “overshadowed” daughter, who narrates this enmeshed, intense, way-out mother-daughter relationship where anything goes “so long as Proust or Yeats was involved”? A relationship that’s not quite a relationship. Rather, “the fact of a relationship, but never the truth of it.”

This fictionalized memoir-in-a-novel centers on a push-and-pull relationship involving multiple themes not always easily detected or obvious that Ireland’s First Laureate of Fiction, Man Booker Prize-winning Irish author, Anne Enright, is known for. Actress, her seventh novel, is an intellectually, emotionally charged expose demanding more than any reviewed here.

Partly because of the often dreamlike, surrealistic prose. Literary fiction that sweeps you away, managing to overpower an already captivating relationship about the lives of two troubled, “hellishly lonely,” conflicted female protagonists.

Katherine O’Dell is an alluring, avant-garde Irish actress and singer born in England yet devoted to all things Irish – theater, literature, nationalism. Her “Irishness would grow more poetic and controlling. Over time, it became a national statement, or national lullaby.” Then, she descended into mental illness. Norah is her “whispered” daughter, damaged too. Loaded with conflicting, ambivalent, suppressed, unsure feelings – another reason the novel demands a lot.

Even under the best of circumstances – and these are far, far from that – Norah might not be a reliable narrator since she’s telling this psychologically complex tale saying, “I will always remember – or think I remember.”

A narrator confused by “the difference between what happens in your head and what happens in the room.” A “star struck” girl; a teenager who couldn’t wait to get away from her mother; a caregiver too young to be thrown into mothering her mother. A narrator too innocent to grasp all the goings on in her Dublin house – men especially: a movie producer, a UCD (University College Dublin) professor, and a priest who also preached “existential psychoanalysis,” trained under a famous French psychoanalyst, Jacques Lacan.

Lacan is referred to twice because Enright wants us to psychically dig deeper than we typically do to think about what’s obscured by two female characters. Or, in a psychoanalyst’s world, what’s happening below the surface, coming from the subconscious. “References are everywhere,” so it seems Enright wants us to check them out.

When we do, we learn Lacan’s work is explained in terms of Identity, Love, and Politics – themes Enright infuses in Katherine and Norah’s unusual story. His theories are also described from the perspective of what’s Real, Imaginary, or Symbolic – similar to Norah’s ambiguous prose. Is what Norah says real, imagined, or symbolic? Actress begs for psychoanalysis.

Psychoanalytic assessment is better for understanding the complex emotions of the women, giving the novel an aching, taunting, hypnotic tone.

“I’m interested in that moment of glamour, which is almost a moment of loss as well. Once you see something so beautiful and false, you’re losing it at the same time. So that was the psychological moment, very, you might say, psychoanalytically rich. It’s about beauty and it’s about possession and then losing the beautiful object to the world.”

Love satisfies and comforts yet it’s palpably abusive, warning “you can also be destroyed by love.” For Katherine, “sex was just part of the great problem she sometimes called Love, and other times Art.”

Norah’s telling is also circumspect having missed out on the normality, stability of a positive role-model mother; she didn’t know her father, didn’t even know his identity or name. A “clandestine” only child, often left behind when her mother traveled abroad. Kitty, their housekeeper, was her savior.

As Norah and the reader are trying to figure out the mystifying actress who grabs, seduces everyone’s attention with her extraordinary “ability to be over the top, just by standing still,” we’re trying to figure out Norah too.

Complacent, ill-equipped young Norah avoided, repressed things going on, burying her head in books where she “always felt safe on the page.” Finally confronting her past, triggered by a doctoral student requesting an interview asking “what kind of mother was she?” A question haunting Norah for decades, answering it in her fifties.

“People ask me, ‘What was she like’ and I try to figure out if they mean as a normal person: what was she like in her slippers, eating toast and marmalade, or what was she like as a mother, or what was she like as an actress, we did not use the word star. Mostly, though, they mean what was she like before she went crazy . . .”

Norah’s reluctant to air her mother’s story feeling it a “betrayal.” Regardless, how can she when her mother “could not explain – even to herself – what was going on”? Moreover, how can Katherine be truly knowable when she was forever moving back and forth “in and out of character”? We get a sense of that as time bounces around back and forth, aided by chapters untitled, unnamed.

It wasn’t easy for Katherine to shed her public celebrity persona into a private motherly one, so fiercely immersed in her craft. An artist who could “just Give Give Give” to an “audience who takes, and takes, and then likes to criticise.” Devastating for “a great believer in the nobility of the crowd.”

As Norah dissects her mother in unnerving scenes that feel manic-depressive, she occasionally addresses someone as “you.” We learn early on you is her husband, who, pointedly, feels more imagined than real, or perhaps symbolic of men who straddle good and bad. (Most men are bad, except Katherine’s father, Menton, an Irish traveling theater actor who “brought Shakespeare and melodrama around the Irish countryside.”) Norah’s husband is ghostly as he’s a reference not a presence, depicted in contradictory ways.

She says she loves him, marvels at their enduring marriage, yet they were “always leaving or being left.” She slips in how “irritated” he was at her inability to write – presumably this novel. Published, unlike her mother frantically, fanatically trying to write plays all night, caring about the written word as much as the spoken one, only to be rejected by Boyd O’Neill, the movie producer. Is that what led her to commit a crime?

Soon after, Katherine suffered a mental breakdown. The author is quite open about hers, in her twenties, ending her career with Ireland’s national television, RTÉ (Raidió Teilifís Éireann); Norah worked for them too. Another similarity between the two is they both now live in Bray, south of Dublin, on the sea.

The prose veers from beauty and consummate artistry to gut-punching anger and abuse reflected in graphic sexuality, violence, profanity, madness. Voyeurism, similar to a terrible car accident, we can’t turn our gaze away from.

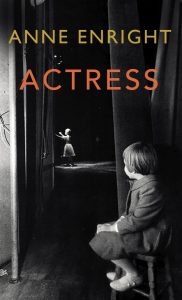

In hindsight, we might have been better prepared if the beautiful emerald green cover of the US edition (matching Katherine’s striking eyes) remained the same as the UK version, a black-and-white cover of a young girl watching an actress on stage. Apparently, inspired by the fraught relationship between Carrie Fischer (Princess Leia of Star Wars fame) and her famous mother, actress Debbie Reynolds.

Motherhood and sexuality are the prominent themes; artistic, philosophical, religious, political, and racial (English towards Irish) themes wrapped up in them.

Through the good and the bad, Actress sticks. Consciously or unconsciously. Or, maybe it’s the magnetic, hypnotic, provocative prose.

Lorraine