Newfound perspectives on Jane Austen’s novels during life-changing events over years (Boston and Chicago, 2012 to present-day): How do you cope when your “world shattered”?

If you’re Rachel Cohen, a widely-read scholar who grew up as a “lonely, reading child,” when she was going through a period of traumatic events later in her life, she became consumed reading novels that gave her things she didn’t have: “definiteness, endings known, bearable, even triumphant.” But unlike millions of readers passionate about Jane Austen, this University of Chicago English professor of creative nonfiction – “biography, art history, the lyric essay, literary criticism, and memoir” – was “appalled” her reading life had narrowed exclusively to Austen over many years, especially since she’d considered Austen’s works less complex than she discovered upon further study.

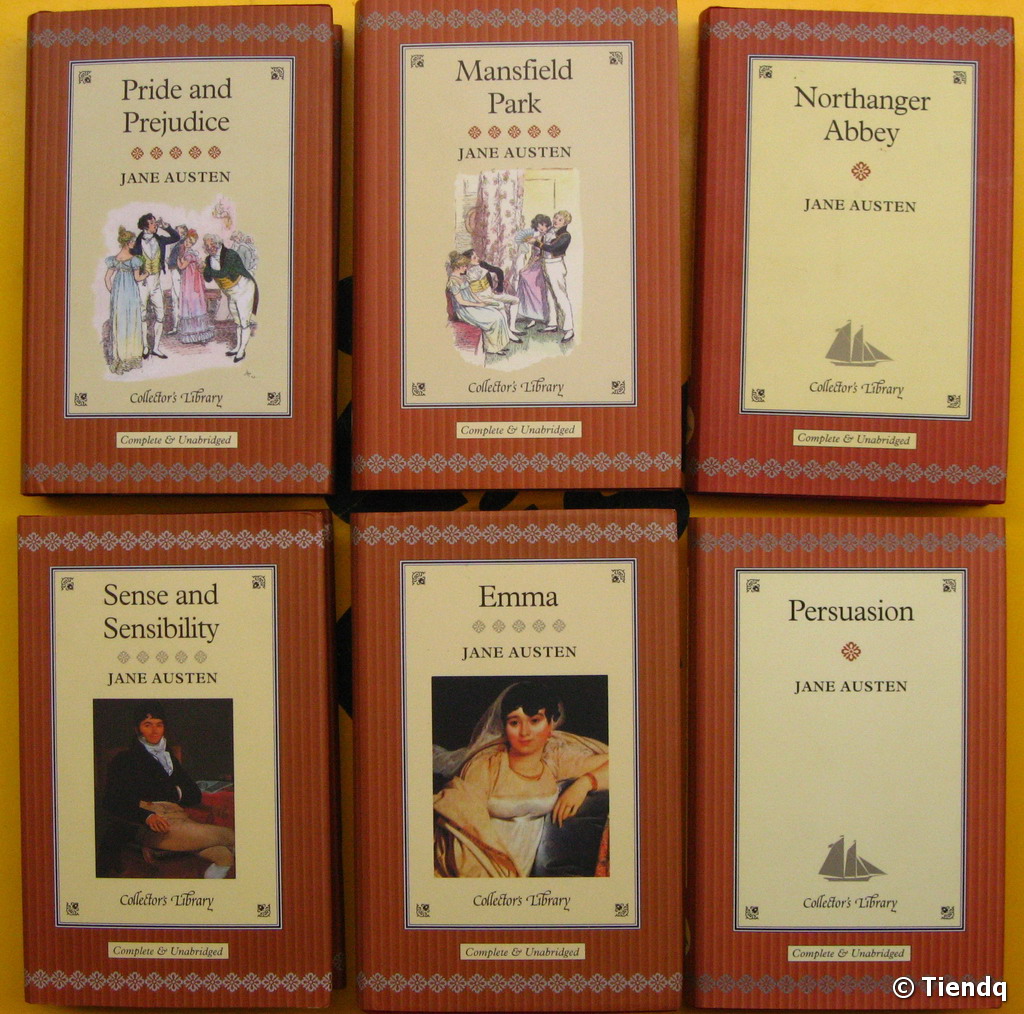

The Austen Years tracks Cohen’s seven-year journey when she “repeatedly” re-read five of Austen’s six novels, leaving Northanger Abbey out because Austen hadn’t “solved it to her satisfaction,” which matched Cohen’s view that it was “opaque.” These were years of personal upheaval, when the dad she was so close to was hospitalized and then passed away a year later around the same time she gave birth to her first child, a daughter she calls S; later a second child, a son, T.

Two extreme emotions – grief and sadness, joy and the daunting responsibilities of motherhood – drove Cohen to seek out qualities and characters in Austen’s world that were comforting. She wasn’t expecting guidance, rather, understanding. Austen “is often not going to be guidance,” she says, but “understanding,” which actually takes “a long time.” Cohen’s inward journey began sometime after 9/11 when the world we knew also shattered.

The author is intellectually patient; asks us to be too. She’s a deep thinker who offers new perspectives on Austen’s appeal and timelessness. Unless you’ve recently read most of Austen’s novels so they’re fresh in your mind, expect to miss some of the memoir’s richness of thought. Still, you’ll feel energized by what you learn and glean.

In an excellent article, psychotherapist and English professor Wendy Jones, who wrote Jane on the Brain: Exploring the Science of Social Intelligence with Jane Austen, asks, “Why so many people love Austen so intensely, and in such a personal way?” She offers insight into the allure for Cohen going through enormous emotional turmoil as a “profound need for empathy, that we’re not alone.” Empathy, more specific than comfort, better explains what Cohen found.

Interestingly, Jones describes our need for empathy as not just during our “sorrows,” but “our joys” too. This illuminates the unusual aspect of Cohen’s memoir, the dual perspectives of Cohen’s relationship to Austen, which mixes seeing things in Austen’s world Cohen wished she had with seeing similarities in her life in Austen’s novels and life. Jones calls these “two kinds of empathy, of recognizing and feeling recognized.”

The Austen Years is probably the least understood book I’ve reviewed that I’ve enjoyed so much. Cohen has devoted a lot of time analyzing a great 19th century British writer resonating so well today, so she has a lot to say. Our tendency may be to put down a book we don’t fully understand, but you don’t feel that way at all. Instead, you’re compelled to take in as much as you can.

As for similarities between Cohen’s world and Austen’s, there’s many, starting with balancing darkness and lightness. Cohen sees the same in Austen’s novels: “Jane Austen wrote in alternation, darker books and lighter ones, dimmer ones of sorrow and bewilderment next to brighter ones of comedy and clarity.”

Austen’s novels may be on your bucket list of classics you want to read/re-read, so it’s likely the memoir will encourage you to do so sooner than later. If so, Cohen suggests beginning with Sense and Sensibility since it’s “a little easier to find the beautiful rhythm that comes in the rest of the books.” That does not mean it’s her favorite. Hands down Persuasion is, including the main character Anne Elliott, whom she loves. The attraction is seen when Cohen writes “nearly everyone in her book [referring to Persuasion] is mourning, in different ways”; and when she characterizes Anne as “quiet, modest, passionate, and alone,” which is how Cohen comes across grieving the loss of one life while bringing a new one into the world.

Readers devoted to re-reading Austen, the Janeites, attest to how many times you can re-read her novels and discover something new, like Cohen. She admits she “missed huge parts of the plots” on the first go-arounds, attributing that to knowing “little of what other people had found in Austen. I had not worked at history, interpretation, biography. I had been too much alone.” Her memoir does not make the same mistake, as her interpretations included consulting a multitude of resources – books, articles, essays, letters, literary critics, historians, writers, friends. Enough to fill fifteen pages in her Notes and Bibliography. These references are printed in a tiny font, which makes them feel even more exhaustive.

One writer she consulted may surprise you, Ta-Nehisi Coates. We associate him with his award-winning books on racism, not the genteel world of Jane Austen. Coates is also a columnist for The Atlantic magazine, who wrote an article in 2011 saying:

“I think Austen erects the most gorgeous and intricate sentences. They move with force in one direction, and with an incredible suddenness turn back on themselves. You think you’re reading one thing, when in fact, you’re reading something else.”

This, of course, is Cohen’s takeaway too. A good example is Sense and Sensibility. She’d thought it a “romantic comedy” – like most of us likely do – but upon closer examination concluded it’s also a “novel of grief.” Reflecting on mourning, Cohen says “grief runs through the whole of life and leaves nothing untouched.” So, it runs through the whole of her memoir, giving it a melancholy tone, despite the wonder of motherhood.

Cohen goes so far as to count how many times crying appears in Sense and Sensibility: twenty-three. That statement alone speaks volumes about the integrity, the thoughtfulness, of her efforts. This may explain why she doesn’t name her daughter, her son, and her husband, M. These impersonal attributions may make her family feel distant and put you off a bit since we want everything to feel intimate, but you do sense she’s given the same seriousness to protecting her family as she gives to the rigor of her work. Note: she dedicates her memoir to all three family members by name, so they’re not really hidden. She’s a serious person. That doesn’t mean parts of her memoir aren’t intimate, like her long years of her uneven relationship with M before they married. She’s kept her family at a distance since her memoir is focused mostly on her relationship, her journey, with Jane Austen.

The one family member she wants us to know is the wonderful man she’s mourning: her father, Michael Cohen. He’s full of warmth, fun, and intellectual curiosity. We see how he instilled in his daughter the same curiosity and excitement for the exchange of ideas. He was “beloved” as a professor at the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor. An esteemed expert in organizational theory, particularly the “character” or culture of organizations.

Michael Cohen’s daughter wants us to understand the loss of a great man as much as the greatness of Jane Austen.

Lorraine