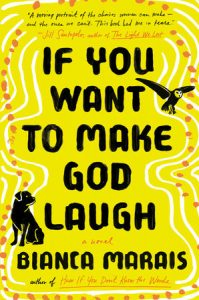

Motherly love overcomes racial injustice (South African villages and capital city, also Goma, Zaire now the Democratic Republic of the Congo; 1993, 1994-1997 post-Apartheid): Almost six years ago, President Barack Obama delivered a rousing speech to a stadium-filled crowd in Johannesburg, one of the South African settings in this marvelous novel, to celebrate the life of Nelson Mandela, whose rise to power ended fifty-years of the racist Apartheid era. This is the same historical period Bianca Marais has chosen for If You Want to Make God Laugh, her second novel. (Her debut, Hum if You Don’t Know the Words, took place during Apartheid.)

While the video doesn’t include the former President’s full speech, his uplifting words and the images are echoed in this memorable work. He spoke about the “moral necessity of racial justice,” knowing that “racial reconciliation,” “equality and justice,” “freedom and human rights” were not guaranteed. But, he wisely pointed out that the spirit of “Mandela’s greatest gift” was achieved and should never be forgotten, though in today’s highly divisive America it seems it has. That gift is:

“Recognition that we are all bound together in ways that are invisible to the eye; that there is a oneness to humanity; that we achieve ourselves by sharing ourselves with others, and caring for those around us.

Imagine a novelist inspired by the glorious ambitions and grace of two eloquent Presidents, turning them into a heartbreaking and heart-uplifting tale showing how formidable it is to achieve racial understanding and compassion, to thoughtfully drive home Nelson Mandela’s message. Couple that with the fears and agony of the emerging AIDS epidemic in South Africa for mothers and their babies, as seen through the hearts of three female characters – and you’ll have the gist of the powerful themes tackled.

Two of the women are white and in their fifties, Delilah and Ruth. The third is seventeen and of Zulu ethnicity, Zodwa. Each keeps their sorrows, regrets, burdens from their pasts secret, to hide their shame and pain. To varying degrees, they accept their fates as a form of punishment: Delilah wrongly believes she deserves a “lifetime of heartbreak”; Ruth punishes herself in destructive ways; and from Zodwa’s perspective “it’s a quirk of fate or a spin of the wheel that decides who must suffer and who will be spared.”

Who is spared is key to the unwinding plot, and to what’s needed to make God laugh.

Delilah and Rose have not seen seen or spoken to each other in forty years. Early in the 435 fast-turning pages you’ll learn their oil-and-water relationship. Zodwa is a stranger to them, until a series of events brings the three together. Chapters alternate between them.

- Delilah is living in Goma, Zaire before it became the Democratic Republic of the Congo bordering Rwanda, where a genocide ignited in 1994 (see In the Shadow of 10,000 Hills). She’s the complete opposite of flamboyant, outspoken, rich, alcoholic Ruth, comparing the two to “shooting stars [Ruth] and mason jars.”

- Ruth is living in Cape Town, then leaves for her family’s neglected farmhouse and defunct avocado farm in a south coastal South African village, a last ditch effort to save a third divorce. Not as well-to-do as she once was, but the only one with money.

- Zodwa’s mother knew the two white women decades ago when she was called Precious. Zodwa has the least, yet she’s the strongest, having sacrificed even more than the others, the one you’re likely to never forget. She’s been living in extreme poverty in a “squatters camp” in Magaliesburg, a province northwest of Johannesburg, to care for her severely ill mother.

A map of locations is included in the book.

While the three have experienced vastly different lives, they have something profoundly in common: motherhood, be it real or “a cotton-candy fluff of yearning.” Of course, they don’t know that when they first end up together in that farmhouse. It’s symbolic of the peace that could be had, but there’s no getting away from racial animosity, crime, and violence just because Mandela became President. “In the new South Africa, white people want to have black friends just to prove they’re not racist, but the only black people they know are their maids and gardeners.”

We meet a lot of “broken people” mourning the death and disappearance of their children; others abandoned by parents who’ve died from the conflicts, AIDS, and are so impoverished they’re unable to care for their babies. More suffering by these three women comes from ostracized loves, due to racial, religious, and cultural beliefs.

Ruth is a believer in signs, not so different than Zodwa’s Zulu culture’s belief in spiritual healers. “Some signs have saved my life,” Ruth says, “while others reminded me that I had a life worth saving.”

If You Want to Make God Laugh wants to remind us that all lives are worth saving. If only people would do the right thing.

You may wonder, like I do, whether an author who wasn’t born and spent much of her life in South Africa (Canada is now Marais’ home) – about the same age as Zodwa when Mandela came to power, and worked with women and children who were HIV-positive – could write such an historically and emotionally poignant novel? Perhaps, but the authenticity stirs, builds, bubbles over.

Delilah and Rose are Afrikaners who speak English and Afrikaans, a language defined in a welcomed four-page Glossary of Terms, found at the back of the book as: “derived from a form of Dutch brought to the Cape by white settlers from Holland in the seventeenth century.” Zodwa speaks English and Zulu, a language spoken by about 9 million people centered in the KwaZulu-Natal province where Zodwa lived with her grandmother, her gogo, until she’s summoned to care for her mother. The lush scenery of this region is world’s away from the filth and dangers of her mother’s shack. The helpful dictionary, then, includes both Afrikaans and Zulu words.

via Max Pixel [CC0]

As for the motherhood connection, a few details. In Goma, Delilah was working at an orphanage, home to over two hundred children, many “countries and missions later,” after she’d left the Catholic church. The children call her Granny, a word used for anyone forty or over; they used to call her Mother when she was younger. Initially, she felt they were “mocking me for my childless state.” Her evolution on motherhood takes her a long time to face up to, while Ruth’s response to mothering is, uncharacteristically, almost instinctual. Zodwa’s is not as immediate, but happens quite soon, and intensifies.

Their stories will become clear, but saying more will spoil the impact, which seems why the author is in no rush to hurry them. She wants us to feel what it takes for her characters to evolve over time, to find common ground. Chapters, though, are short, flow easily into one another, allowing us to absorb the challenges confronting these women.

Racism and its consequences are at the forefront. But a mother’s love is color-blind, as the women discover the bonds of motherhood, mothering, are the most powerful of all.

Lorraine