Dairy cow whisperer – who’ll change the way you think about cows, including their role in reducing global warming (Reflections on more than ten years of raising dairy cows in Wyoming): How many teenagers “dreamed of having a dairy cow?” like Shreve Stockton did. Or were voted “Most Likely to Wake Up in a Strange Place?” like Stockton tells us in the opening sentence of her intimate and evocative new memoir on being in the 1%. Not the 1% of wealthiest Americans, but the tiny fraction of “grass-finished” 100% organic dairy cow farmers among an industry dominated by the “Big Four”: “concentrated animal feeding operations” or CAFOs. Stockton may still be unique from other one percenters. She’s had the most intimate and awesome experiences with dairy cows.

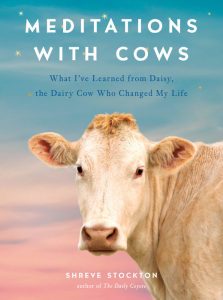

Between Stockton’s unusual dairy cow raising story, her poetic prose, stunning photographs, and eye-opening, timely information, Meditations with Cows is a beautiful, inside and out, meaningful read.

At twenty-eight, Stockton’s dream and high school prediction came true in a small rural town in Wyoming, a world far away from New York City where she’d lived and thirty miles from any town bigger. A world she got lucky to have found for someone who feels “just enough is everything.” She started off living in a bare-boned, 12 x 12 foot cabin on a 40-acre piece of property leased by someone she met walking on the side of the road, when he – Mike – was in a pickup truck. Daisy is the cow who changed her life; Mike made that happen. Her story is full of new experiences that transformed her wanderlust life in profound ways, learning to live “beyond the noise.” In the moment, “wholly present.”

Daisy, who graces the cover, was her first dairy cow love. She’s mostly a Brown Swiss American breed, mixed with some of Britain’s Jersey breed. Both are known for their abundant milk production. Stockton became in “awe of the intimacy of milking”; of “how you could rest your cheek and forehead against her warm belly and milk”; of “farm fresh milk” that was “ecstasy in liquid form”; and how Daisy’s “maternal instincts bloomed like a Wyoming sunrise: epic, encompassing, brilliant.”

It’s not just Daisy’s striking looks, but her friendliness, intelligence, intuitiveness, and loyalty that Stockton, and the reader, marvel at; Stockton spends a lot of time “marveling” at being loved by her giant and gentle cows. We marvel too at the marvelous pictures of the author lying in a golden field resting, meditating, with her arms spread out across Daisy’s big white-blond body, and stretched out across the top of a 2,000 pound, black cow she adopted, with her cowgirl boots hanging down his rear. She named him Baby, but he gained 100 pounds a month so by the time he was nine months old or 1000 pounds his name was changed to Sir Baby. Some of the other gorgeous photographs sprinkled throughout can be found in these links: http://honeyrockdawn.com/category/daisy/, and https://shrevestockton.com/wordpress/#about2. Stockton isn’t just a literary artist, she’s also a professional photographer.

Milking Daisy twice a day, the author soon found herself with far more gallons of milk than she could possibly drink or share. This led her into the dairy world of making yogurt, buttermilk, and butter that “gleamed like sunlight.”

Milking Daisy taught the author how fundamental trust was to the process, reinforcing the unique human-animal bond. Daisy taught her the true meaning of meditation: a state of peacefulness when your mind is free of the daily stresses of life, much like how we feel when we go on vacation or spend time in nature. For us, these are escapes; for Stockton this is a good portion of her life.

Stockton wants us to know a lot about cows, starting with the basics: the word cow. She explains the differences between adult males and females: a male that can breed (bulls) versus one that can’t anymore (steers); a virgin female (heifer) compared to a female who’s birthed a calf called a cow. To the rest of us, they’re cows, but the distinction matters. Daisy was a young heifer when she met Sir Baby a bull. They bred Frisco and Fiona, whose mixed genes turned her into an attractive “strawberry” color. The bond intensifies when you’ve observed, assisted in their births, and raised them with “love while we can.”

Mike is also seen as a growing relationship. The two are like dairy cow soul-mates. After he lost his daughter, he turned his grief into something restorative. He too cares deeply and differently about the life of a cow. Some are Special Projects he never sells, letting them die of old age, which is not done with “tens of thousands of cattle to upward of a hundred thousand cattle at any given time” packed into pens without regard for their health, freedom, and safety, “a reflection of how the rest of our economy works.”

Still, there’s so many more cows raised that cannot possibly be kept. Ethical questions arise as to how to reach scale humanly. Stockton cannot bear to have her cows spend their last days in confinement, so she entered another new world: the risky business of selling organically farmed beef, forming her own company called Star Brand Beef. Her journey and success are documented in these pages, along with an alarming picture of how most of the cattle business operates. Risky as a writer too when you’re as passionate and well-read as Stockton is, to avoid sounding overly preachy. She’s an activist at heart, who wants to back up her opinions with facts. She does so by quoting a wealth of resources, referenced in a substantial bibliography that shows she’s as devoted to health and the environment as she is to her dairy cows. By weaving technical data and suggestions about doing things differently in between scene-after-scene of fascinating stories about raising Daisy, her babies, and other cows (like 3M and Six), Stockton has found an effective way to pull off her human-animal stories and her environmentalism.

Of course, not every scene is Pollyanna. Plenty of scary emergencies that require fortitude and wherewithal, such as a difficult birthing when a calf is breech and the vet is unable to arrive on time, when life is on the edge. Death and grief come too, but there’s never a time when the author regrets. It’s all been worth it.

Wyoming’s weather is also a formidable presence. The temperature drops to minus 10, 20 below zero in the winter, and pounding rain in the middle of a 100 degree summer can be treacherous when the dirt where the cows roam gets too deep and muddy like quicksand, described in a vivid rescue.

The memoir also provides lessons in appreciating solitude “as absolutely divine.” When “it was impossible to feel lonely while lying on the earth or beneath the explosion of stars.” When you’re “surrounded by too much life to feel alone.”

The memoir is also about belonging. “When you belong to a place, you are in a relationship with the land. Being in a relationship requires attention.” Stockton’s voice is one of gratitude for “the interconnectedness of everything.”

Stockton’s transformation went from “What can I get?” to “What can I give?” to “How can we achieve together?” The million-dollar question we’re all wondering about. The answer gave her “an almost superhuman endurance.” What could it mean for the rest of us?

Lorraine