A seascape shaping WWI history, artists, and fiction: The year Scottish architect/artist Charles Rennie Mackintosh painted there (Suffolk Coast, England, 1914-1915): This gorgeously written novel paints moods with words – wistful, soulful, hopeful – blending facts and fiction the way warm and cool watercolors blend into one another. The painted canvas, Mr. Mac and Me, is perceived as earthy tones, understated beauty that glows.

A seascape shaping WWI history, artists, and fiction: The year Scottish architect/artist Charles Rennie Mackintosh painted there (Suffolk Coast, England, 1914-1915): This gorgeously written novel paints moods with words – wistful, soulful, hopeful – blending facts and fiction the way warm and cool watercolors blend into one another. The painted canvas, Mr. Mac and Me, is perceived as earthy tones, understated beauty that glows.

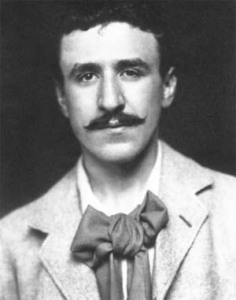

Aesthetic prose is exquisitely fitting since this is partly a biographical novel about the year the misunderstood Scottish architect, Charles Rennie Mackintosh, escaped to the alluring Suffolk coastline of England immersing his melancholy self into his early artistry: flower watercolors. Esther Freud has matched the mood of Mackintosh’s beautiful watercolors with her atmospheric prose.

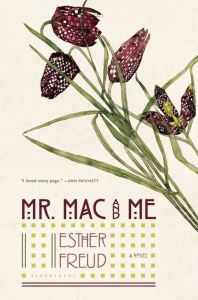

First, a confession. I fell in love with this novel – or the idea of it – before it transported me; before I laid eyes on its lovely purple bell fritillaria cover, depicting one of Mackintosh’s painstakingly painted flowers. He made this watercolor in 1915 when he lived in the small seaside village of Walberswick, as WWI dawned – the same village Esther Freud lives in. Sitting on Britain’s northeastern coast near London, surrounded by a string of villages (Southwold, with its ferries, the largest), it hugs the North Sea across from Belgium, where battles were fought. I was charmed by the author’s 400-year-old stone cottage, where you can envision her inspired to poetically craft Mr. Mac and Me, her ninth novel. To see if you might be as enamored, see At Home with Esther Freud.

The parallels between Freud’s background and the novel also fascinate. Her father was the artist, Lucian Freud, considered a leading British portraitist of the 20th century. The author, then, grew up in an artistic home watching her father paint, like her story’s narrator watches “Mr. Mac.” Lucian Freud’s work is characterized as “moody.” His daughter has penned a wonderfully moody novel. The prose has a poignancy and air of mystery and wonder about “Mr. Mac” and Suffolk’s land and sea, a powerful presence rich with wild, low-lying vegetation. Freud lures us into the daily chores and comings-and-goings of village life “where there’s nothing that gets by a village this size.”

The “Me” in the title is the narrator: 13-year-old Thomas Maggs, who strikes up a warm friendship with “Mr. Mac.” He’s mature beyond his years, having had to bear the burden of being the only surviving son of six brothers (he has two sisters, Ann and Mary), and a useless alcoholic father. The family runs an inn, with one of the village’s two pubs attached.

Tommy’s voice is sensitive. He and “Mr. Mac” have several things in common: physical disability (Mackintosh was born with a club foot, whereas Tommy’s “twisted foot” seems due to a sinister cause he’s averse to explaining); a passion for drawing; a keen appreciation for Nature; vigilant beholders of the sea; and a palpable lonesomeness borne from their “longings.”

Today Charles Rennie Mackintosh is acknowledged as the “Father of the Glasgow Style,” famous for designing the Glasgow School of Arts, which tragically caught fire around the time the novel went to press! (Restoration underway.) But in the early 1900s, his avant-garde Art Deco designs, which enveloped the totality of a structure (interior as well as exterior), were not well-accepted in his native Glasgow as they were in Europe, especially Germany and Austria. I’d never heard of Mackintosh until now. He has legions of followers (www.crmsociety.com).Mackintosh is spotted roaming the seashore at night with “spyglasses.” Since “this is where the enemy could land,” and he “looks for all the world like a detective,” Tommy is naturally wary of him. He also speaks a dialect that’s hard for Tommy to understand; it sounds German. I googled it: Glasweigian (or The Glasgow Patter) is spoken in Glasgow and the Scottish Highlands, where the summertime “herring girls,” Betty and Meg hail from. It doesn’t help that everyone in the neighboring villages is being urged to be on the lookout once the Defense of the Realm Act (DORA) was enacted in August 1914 and posted along the Southwold pier.

Mac and Tommy’s friendship begins by walking the sea together. Then Tommy starts spending time in the Mackintoshes’ loving home. Kind Margaret Macdonald Mackintosh is also an artist, known for her unconventional gesso panels adorned with Glasgow roses. After Mackintosh gives Tommy a box of watercolors, they draw together in a “thick, warm silence.” Tommy realizes “Mac is not a danger. I can see that now. He may have even been sent here to keep us safe.” Unfortunately, others believe he may be a German spy. How sad for an artist who “made places for poets.”

Tommy is drawn to the sea, but his mother seeks a different life for him. So he draws boats anchored on the waters and battleships from ship models encased in glass cabinets in the Sailors’ Reading Room, where he sneaks away to when he’s not tied down to his many responsibilities at home and school. One is a paying job as assistant to rope-maker George Allard, turning a wheel. Rope-making is a “dying art,” laments Allard. The war needs metal for barbed wire, not rope.

Tommy recognizes Charles Rennie Mackintosh is “nothing like any of the artists that I’ve seen.” He’s seen plenty, inspired by the coastline. (Danky, a villager Tommy looks in on, models for artists.) By now, Tommy endeavors to see the world through Mac’s eyes. He’ll stare at:

“one pebble shaped like a heart – or almost – and I think of the pamphlet of Mac’s designs. There were hearts carved into a bookcase, and a cluster of them floating high up in the panel of a bedroom door. There were small dropping hearts in lamps, and most beautiful of all, a square of metal molded to the rise of a heart.”

Mackintosh’s heart is best revealed through romantic letters he wrote to “My Margaret,” as she often had to leave him for lengthy periods of time to tend to family crises. She affectionately called him Toshie. He writes: “There are only three important words that could take the place of the rest. I Love You. I hope you find them here in every line.”

The haunting drumbeat of war is sketched into sentences too: in the names of battles Tommy must memorize at school – Battle of Tannenberg, Heligoland, Bight, Siege of Tsingtao; in the sounds of guns heard as far away as Flanders, and then, closer, overhead, the Zeppelins; in the canons that must be buried on Gun Hill; in Ann’s anguish Jimmy Kerridge may have perished on the HMS Formidable in the Channel nearby, a battleship Tommy drew. “Ann needs me,” he says, racing to console her. We want to embrace this compassionate young fellow with dreams of the sea. Mackintosh feels warmly about “our boy” too.

It’s that same warm emotion Freud keeps brushing in with the somber, buoying us: a landscape blessed with daffodils, celandine, hawthorn, sweet william, gorse, aubretia, heather-bell, larkspur, bluebells, hyacinth, hellebores, narcissus, witch-hazel, elderflower, anemone, and yes, those lovely fritillaries.

Moved by the landscape, Mackintosh painted flowers “fresh and breathing.” Esther Freud matches him with “fresh and breathing” prose.

Lorraine