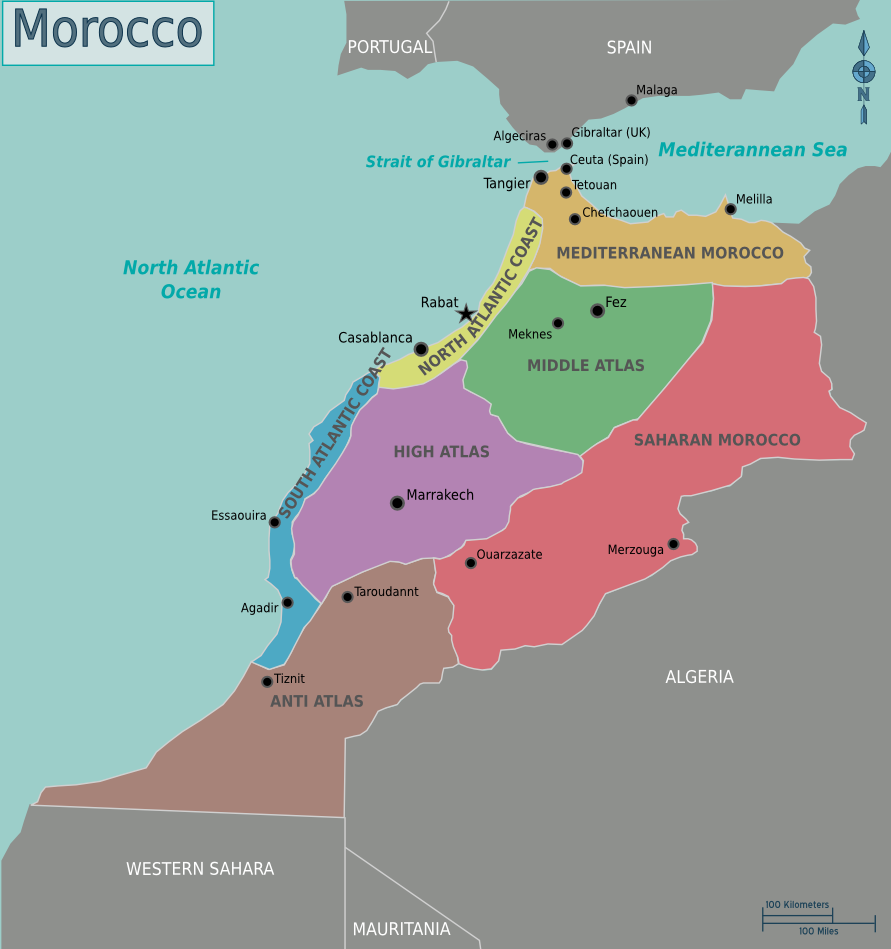

Toxic, intoxicating Tangiers/Tangier (Morocco, 1928 and 1978): Laura Madeleine’s sensory prose tantalizes with the tastes of food, sweets, and atmospheric smells. In An Echo of Scandal, her fourth historical novel, she mixes in another powerful ingredient: spicy, pungent alcoholic beverages concocted for the exotic, sultry, teeming north African city Tangier, Morocco. Fabled, multicultural, and centuries old (and new), it sits “at the edge of the world,” a short ferry to Britain’s Strait of Gibraltar and Spain’s southern Andalusia region.

Formerly an International Zone (Interzone from 1912 – 1951), the city is “nothing but layers.” It’s “built on stories,” an ideal locale for Madeleine’s trademark of inventing layered stories separated by decades, one historical, one modern-day.

What’s echoing is a secret protected for fifty years the contemporary protagonist – Sam Hackett, wandering American ex-pat – stumbles upon, leading him back to the 1928 Spanish main protagonist, Alejandra del Potro. From “the Tangier of now into the Tangiers of then.”

The two spellings of the city – with or without an s – is intentional. While the Internet says the two are synonymous, the author uses these to distinguish historical periods – Tangiers for the past, Tangier for the present – to tell two stories of two very different characters who “didn’t fit in anywhere else,” until they landed in Tangiers/Tangier.

When we meet Ale and Sam they’re traveling in different worlds. Sam is an author with writer’s block who depleted his funds vagabonding around Europe searching for inspiration for a novel. Tangier is his last hope, or else he’ll have to return home. Ale is a watchful sixteen-year-old without a last name living in an inn that doubles as a brothel in Cordoba, Spain. She has no idea how she got there, either “born there, or at least left soon after,” adopting the inn’s name for her last name, Del Porto. The novel opens when she’s been assisting the cook, Ibrahim, her only friend. Tender of age but old enough to now serve as prey for garish men who take advantage of destitute girls whose survival depends on obliging their desires and those of the inn-keeper/madame, heartless Mama Morales. By page 3, something terrible happens to Ale, sending her fleeing; something she’ll have to keep secret or risk being arrested for a crime she didn’t commit. Already, we’re hooked as her fate feels sealed: she must keep running away from her past, hiding her identity.

By the time Ale reaches Tangiers, her existence is wretched – lurking on the dangerous streets scared and penniless, painfully disguised. She’s been through so much and yet her tale hasn’t really begun.

Fast forward to 1978: Sam purchases a leather writing case at one of the myriad market stalls in the old city (medina) that courses through narrow passageways. Spending precious little monies he needs for rent, he buys it from a friend, Abdelhamid, who pitches the sale as an omen, one writer to another. The case and contents contain clues that propel Sam to dig into a mystery from 1928 – Ale’s time.

The case provides enough evidence for Sam to fantasize the plot of a mystery for his elusive novel, if he can unlock the story of the case, which he imagines involves “drugs and glamour and mistakes.” The clues include the name del Potro, gold initials, and another name the reader will see as somehow linked to Ale. Sam’s imagination may sound as wild as Ale’s Tangiers, but it fits an international city with a dramatic history and one known to have inspired writers.

Sam and the case become inseparable, with serious consequences, more mysteries, and lots of twists and turns. As Ale’s and Sam’s stories unwind, they parallel each other. The reader itches for these to converge, which they do, as the novelist has done before. When they intersect, two timeframes feel like they’re happening at the same time.

You will not tire of the author’s separated-in-time intersecting style. She’s a pro at keeping the suspense going and going, along with complicated romances. In this novel, romantic tension echoes unusually.

Another familiar element are characters that are cooks and bakers of sweet things and life-saving bread. This time Ale fakes her way into being a real cook. Most of her chapters are introduced by an alluring, potent alcoholic recipe befitting the city’s seductive setting and legendary history.

The author once baked cakes from recipes she created for a UK blog she also wrote for, Domestic Sluttery. Did she create the alcoholic concoctions foretelling Ale’s world? (For the novel’s launch, she enlisted an award-winning bartender to create a “unique cocktail”.) Drink names offer hints about scenes and moods.

For instance, Ale’s story begins with Blood and Sand, so strong you “break out in a sweat . . . an experience rarely repeated.” Indeed, it’s one Ale prays she’ll never repeat. For her next chapter (the two storylines go back and forth in time) Have a Heart is the drink because it draws from critical life lessons Ifrahim taught her: being a cook cast a “kind of magic” – “stove spirit” for the “power and control that came with feeding people.” Advice Ale took to heart when she made her way into Tangiers, allowing her (at great peril) to “carve a space for myself in a world that didn’t want me.”

An Echo of Scandal sets its sights on new territory for Madeleine, whose first three novels are set in France. For those who don’t know about the intercontinental history of Tangiers/Tangier, the commingling of Arabic with French, Spanish, and English, it’s a fascinating read.

Tangiers is where Ale’s destiny is set in stone at a covered-up villa in the oldest part of the city, the Casbah. On the author’s blog, we’re told the inspiration for this hidden enclave was Dar Zero. In the late 1600s, the residence was owned by Britain’s Samuel Pepys (best known for his diaries), when the city was occupied by the British. Last year, the home was featured in Architectural Digest, where the 100th birthday of a famous French designer, Charles Sevigny, was celebrated on the rooftop of the estate overlooking the bluest of seas.

Ale ends up at its fictional version, named Del Portuno, owned by a rather mysterious, charismatic British fellow, Arthur Langham. You’ll be guessing who Arthur really is until the end. Another character, then, whose identity is concealed. His wealth and frequent disappearances are shadowy, constantly hosting lavish garden parties for questionable guests who overindulge in food, drinking, and smoking of kif in a sebsi pipe. What’s really going on here beneath the smoke and mirrors?

Ale’s recipes/chapters are “not for the faint of heart.” Like the drinks Twin Six, “smooth, and very deceptive”; None but the Brave with “bitter allure”; and the Epilogue’s Last Word, which aims to “cleanse the palate, when the day is done.”

Ale’s and Arthur’s story is not just one of danger. For a time, it was filled with the smells of “ancient rose petals,” “honey-slow heat,” when Ale’s world “was as soft as cinnamon.” At her happiest, she “wanted to drink the light. It would taste of pomegranates and cold butter, strawberries wet with dew and honey dripped from a comb.” There’s a lovely, sensual rhythm to the prose.

Roses and cinnamon are fragile. Ale’s extraordinary life is an emotional roller-coaster, since “identity can be a slippery thing.”

Lorraine