Why one woman’s selfhood journey resonates (New York City and Long Island, New York & rural northeastern Pennsylvania; 2001 to present day): Searing and soaring, Kelly McMasters’ memoir-in-essays that span and shift over twenty years emotionally affects us differently than traditional memoirs.

“A truly successful essay collection can reveal the author processing experiences at many different points in time and through many different lenses . . . the distance afforded by some multivalent lenses can allow an author to regard one’s younger self as a different character, a different persona. This can create an unease or uncertainly that is exciting, and also very relatable to the reader.”

Elizabeth Kadetsky, “The Memoir in Essays: A Reading List,” Lit Hub, April 29, 2020

Nineteen essays, each stunning, building on each other. Personal, with an honesty that must have been emotionally exhausting to dredge up and make sense of. Influenced by historical events, cultural discord, and a philosophy of appreciating the good not solely the bad. More of a coming-to-terms with the way things must be, but not until tirelessly trying to change the trajectory. The tone is melancholy, sorrowful, poignant, nostalgic, at times wondrous, but not bitterness. “There’s romance inherent in loss and nostalgia,” McMasters graciously says.

Calling The Leaving Season a memoir-in-essays versus a memoir magnifies the push-and-pull tension of a contemplative journey of self-discovery, even if aspects are unlike ours. Navigating different stages of life – coming-of-age, career, motherhood, divorce, single parenting – resonate. When to make a life-changing decision to leave a place, job, city, marriage? What’s gained and lost? Reflections that give voice to the choices, juggling, and struggles women face, exploring what it means to be a woman true to herself, needs, family?

The opening line of, “Home Fires,” the first essay, sets the stage with one of McMasters’ two sons asking: “WHAT SHOULD WE SAVE, MAMA?” The profound question isn’t just what would you take if you had to flee a fire, but an existential one. What should you pay close attention to that matters most to you?

The prose is emblematic of someone who’s dwelled in the world of books and words. As an only child, McMasters found solace and pleasure in the library near her Long Island home. Contributor to a delightful, eclectic array of magazines – literary, tech-related, pop culture, children’s – she’s been teaching words as an English professor at Columbia University and elsewhere; today at Hofstra University, circling back to her home roots.

Home as a physical place, geographical/environmental landscape, and deeper psychologically isn’t something just thought about in these essays. In 2017, the author co-edited the essay collection, “This is the Place: women writing about home.” She’s also written the 2008 award-winning, “Welcome to Shirley: a memoir from an atomic town,” about her hometown near Brookhaven National Labs, adapted into a documentary.

The Leaving Season is predicated on a dream that may not have “ever truly existed in the first place.” We sense the handwriting on the wall before McMasters, perceiving leaving as failure, tugging at our heartstrings because she tried so very hard to make the dream of a place and a marriage work out.

Opening in Manhattan 2001 when McMasters found herself standing outside the World Trade Center watching the twin towers burst into flames, staring in disbelief at people jumping out of the windows of burning skyscrapers. “Home Fires” summons up a “spectacularly dramatic catastrophe” and then, in the next breath, linked to the emotional catastrophe of a ten-year relationship, six married, with a “moody” artist anonymously named R. ending in divorce. “Marriage, after all, is just one long exercise in controlled burning,” she concludes.

McMasters didn’t leave New York City after 9/11. She did after 2006, when the USS Intrepid got stuck in the Hudson River leaving for its new home and identity: the Intrepid Sea, Air, and Space Museum. Metaphorically, that’s when it hits her that the “girl I once was still stuck.” She’s twenty-five. In “Intrepid,” the second essay, she assesses: “Sometimes, staying docked seems the safer option. But everything in New York moves on eventually.”

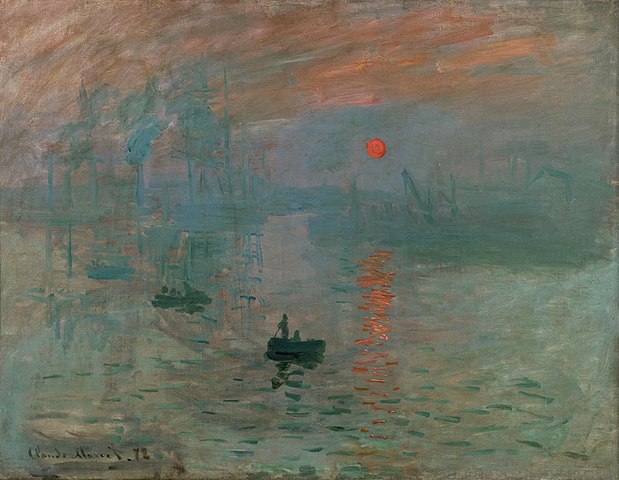

Before the moving, leaving, a few essays are interjected about her backstory with R. Unsure of herself, she was drawn to his “certainty” and differentness. “Invigorating, or terrifying,” but emotionally draining more than anything else. Pained when the impressionistic portrait painter refuses to paint her picture, and yet, fantasizing of not only having a room of one’s own but a home, alone, like Georgia O’Keefe. (Marriage wasn’t in her plans, nor motherhood.) Later in the “Stone Boat,” R.’s artistry is characterized as “exaggerated expressionism” with an “obsession with color and pattern.”

R. had been successful in the avant-garde center of the art world, but a rude awakening awaits when the couple move from Brooklyn to an isolated (on ten acres) “1860s eyebrow colonial farmhouse” in a rural “area with more cows than people.” Three hours from Manhattan, yet worlds away. “Part of the allure is to be a different person yourself.” But how far are you willing to go?

This was a place of “savagery and beauty,” where the “normal rules of society did not apply.” Driven by hunting seasons, broken men “powerless became the powerful.” For a while, McMasters gets lost in sharing the “wonders” of Nature, harkening Rachel Carlson, with her two young boys. When she looks back now she sees herself “separate from the person I know myself to be out in the rest of the world.”

Playing psychologist, we see a marriage likely doomed from the start due to a string of bad luck compounding on itself. R. had his first heart attack at thirty-nine right before they married; his second right before they moved into the farmhouse. Was he suffering from clinical depression gone untreated? How much of his disinterest was affected by his medical condition? Anger ignored before they left New York City? How much was he affected by the “feral quality” of a place not even on a map that unfolds in the essays, “The Cow,” “The Ghosts in the Hills,” and “Lessons from a Starry Night”?

How much pain could have been prevented had they focused on thoroughly vetting the stone farmhouse in need of tremendous repair and renovation, R. could no longer do? McMasters assumed, no griping, all the mounting bills, balancing several literary jobs at time including commuting to Manhattan. Mounting too was her anguish of a father disengaged in co-parenting, fatherhood. Intensified in the essay that gives the collection its name, “The Leaving Season.” But, she persists. For the sake of her children, not for herself.

It’s not until the gorgeous essay, “Bookshop: A Love Story,” that McMasters does something for herself and her dream comes closest to reality. Bursting with joy, hope, and a bit of “much-needed magic,” she and R. opened a joint bookshop and art studio on the closest Main Street to where they lived in Honesdale:

By DWilliamsFrey [CC BY-SA 4.0] via Wikipedia

“Ultimately, it’s this love of books that buoys me,” she wrote in a column she pitched for The Paris Review, “Notes from a Bookshop.” This is when she realizes how much of herself she’s lost. Sadly, the dream lasted only a year.

“Our Castle Year,” “Suspended Animation,” “Finding Home,” and “End Papers” amplify the leaving, progressing to a heartfelt belief “family doesn’t have just one meaning.”

The Leaving Season shows us there’s dignity and grace when your dreams don’t come true. “By taking away, I could be creating room for more.”

Lorraine