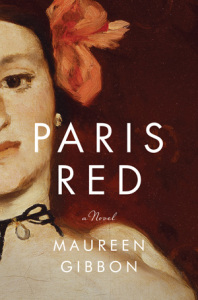

French Realism: Édouard Manet and his “modèle de profession,” Victorine Louise Meurent (Paris, 1862): The first clue you get that Maureen Gibbon’s 19th-century historical novel about the French painter, Édouard Manet, and his muse, Victorine Louise Meurent – he 30, she 17 – is going to be risky and provocative is that of his more than 400 paintings, the one selected for the cover is Olympia. The full painting is a nude, one that caused such a stir critics did see red when exhibited at the Salon of Paris in 1865, two years after Manet finished it, after the novel ends.

French Realism: Édouard Manet and his “modèle de profession,” Victorine Louise Meurent (Paris, 1862): The first clue you get that Maureen Gibbon’s 19th-century historical novel about the French painter, Édouard Manet, and his muse, Victorine Louise Meurent – he 30, she 17 – is going to be risky and provocative is that of his more than 400 paintings, the one selected for the cover is Olympia. The full painting is a nude, one that caused such a stir critics did see red when exhibited at the Salon of Paris in 1865, two years after Manet finished it, after the novel ends.

Manet’s nude is considered the most famous of that century. It may not be the painting non-art historians like myself are most familiar with (or most enamored with). Those are his impressionistic masterpieces of later years – boating, beach, café, railway scenes – that evoke a “dewy-eyed” loveliness, which the avant-garde Olympia is not. But Gibbon’s goal is to pen something original, like Manet’s passion to “paint something entirely new.”

She does so with spare prose that creates an aura catching Manet’s shadowy, mysterious, erotic world, which means her novel isn’t soaked in details, nor the totality of the artist’s career. Instead, it’s a window into Manet’s art when he created a sensual painting that shocked the Parisian art scene, giving us glimpses into the inspiration of his early years, pioneering the French realist art movement.

Édouard Manet Self-Portrait, 1879

via Wikimedia Commons

Here we see Manet’s devotion to art that is honest and realistic not romanticized, the prevailing preferences of the time. The same can be said of the author, who wants us to see the darker side of the City of Lights. The novel is best appreciated like a great piece of art in a museum: by looking and seeing, understanding all by ourselves, with just enough details to intrigue.

So, despite the short chapters – sometimes only a one-page impressionistic paragraph, like the artist sketching – this is not a breezy read. The prose is nuanced, echoing Paris when the lights are gray-blue. We sense what it might have felt like to have been Victorine, who tries so hard to grasp Manet’s “not-simple” paintings, because we’re compelled to understand what the author wants us to see. Gibbon acknowledges she’s thought about Olympia for ten years, so her vision and impressions interest us almost as much as Manet’s or his model’s. (“I am trying hard to understand what it all means to him because I know that it does mean something.”)

There’s a sadness that permeates Victorine’s voice – our narrator – and the evocative prose. Apparently, not that much is known about the real-life young woman who posed for Olympia, allowing the author the freedom to speculate. Artistic freedom – Manet’s, his muse’s, and the author’s – a worthy theme.

What the novel tells us about Victorine is that she’s a precocious 17-year-old working-class girl, a silver burnisher. She relishes the tools of her trade, learned from her working-class parents: her father an engraver, her mother a seamstress. But it’s not until we’re more than halfway through that we’re even sure of her real name: Victorine Louis Meurent.

That’s because when the novel opens she’s called Louise by her intimate friend, Denise, not her lover, more like a sister. They share a shabby room, even the same bed, toiling away at the same silver shop barely eking out enough money to live. That shopworn look is what Manet spots on a street. He makes advances to them both, teases about their names, a “ménage à trois” at first. He’s sizing them up: Denise, the brunette, with “a kind of sweetness about her”; Louise, the emboldened redhead, craving much more out of life.

Louise/Victorine knows she’s “different from everyone else.” Hers is a restless yearning to be noticed and touched – to be someone. So she makes a crass sexual move to grab Manet’s sole attention. Turns out she’s a far better match of the two to become his model: she enjoys drawing, colors, details, and, most importantly, is very willing to experiment.

Victorine Meurent by Manet, c. 1862

via Wikimedia Commons

Victorine has been sizing Manet up too. Her intense desires “not to be ordinary” are matched by his intensity about realism in art (“there’s only beauty in what’s real”). A poignant scene finds Manet rubbing away much of a canvas he disliked, which upsets Victorine because she doesn’t want to be “erased.” Manet sensitively explains it’s not the memory of the woman he painted he removed, just brushstrokes and composition. It’s a marvelous example of his softness. Indeed, Manet is a sensitive man, not content to “paint people at the edges.” And yet he’s veiled, hiding his face behind a bushy beard. (“There is something fine-grained about his face in spite of the riotous beard and moustache.”)

Artist and model also share a fierce independent streak. Manet has the luxury of being an independent artist. He has money to pay Victorine, presumably coming from a well-to-do family, so he’s not enslaved to paint to please the aristocracy. Instead, he painted what he saw. Victorine may adore Denise, yet she risks striking out on her own for “whatever it is in me that wants and wants – it is as big as the sky and keeps going.”

By the time Victorine has grown comfortable posing nude for Manet, she’s taken the black ribbon necklace on the book’s cover and made it her own. It’s a pivotal moment, seeming then to transition from being Manet’s model to his rebellious source of inspiration, his muse. By now he’s calling her “Trine,” an affectionate name reflecting the sexuality of their artistic relationship.

Was their real-life artist/muse relationship as sexual/erotic as depicted? Not clear. What appears certain is Victorine was Manet’s most favored model. Did he love her? Not clear either. He cares for her, is concerned about her finances, is kindly and respectful in the privacy of his studio and publicly among his contemporaries, but Manet is an obscure man with another life.

Most certain is his ardor for his art: “That is the thing that I cannot get inside: what it must be like to love something – a thing – so much.” Did he make love to her so she’d trust him completely? To capture Victorine’s essence, she must unabashedly be at ease, in her most personal, raw moments, especially if he is to paint the soulful expression in her eyes. When Manet finally shows Victorine Olympia, she’s moved that there’s “nowhere to look in the painting except my eyes.” She recognizes that expression: “I know what it feels like to look that way … When my grandmother died. When my heart was broken.” Victorine’s soul, then, is forever a part of Manet’s “groundbreaking” art. Now she has what she’s desperately wanted: she’s unforgettable.

Numerous sprinklings of references evoke the era – names of Parisian streets in the 1860s, French phrases, Manet’s artist and writer friends. At times I wished for an appendix, maps, dictionary, but the truth is that precision isn’t necessary since the novel is about sensing moods and artistry, which it achieves.

Still, once read, I googled Manet’s friends, as some names were familiar, others not: Félix-Jacques Antoine Moulin was a photographer whose photos Manet uses to see the “effect of shadow and light;” Henri Fantin-Latour was a portraitist and painter of flowers; Charles Baudelaire, a poet; Honoré Daumier, cartoonist and painter; Louis-Émile-Edmond Duranty, author; Zacharie Astruc, sculptor and painter; Tonin, turns out is An-tonin Proust, boyhood friend and journalist; Tony Robert-Fleury, another French painter; and Alfred Stevens, a kindly, romantic Belgian painter.

Just as Manet pushes Victorine to observe her reactions, the author pushes us. Like the famous artist and his muse, she’s “bold enough to tell the truth.”

Lorraine