A family cursed? – A fantastical modern tale tied to generations of a family’s circus history (set in a fictional town on the Long Island Sound; backstories traced to 19th–20th century traveling circuses): The current issue of Poets & Writers magazine cites an MFA course devoted entirely to crafting first paragraphs. Herein, I submit The Book of Speculation for a case study.

A family cursed? – A fantastical modern tale tied to generations of a family’s circus history (set in a fictional town on the Long Island Sound; backstories traced to 19th–20th century traveling circuses): The current issue of Poets & Writers magazine cites an MFA course devoted entirely to crafting first paragraphs. Herein, I submit The Book of Speculation for a case study.

Chapter 1 opens on June 20th (the calendar matters). The voice, our narrator, is Simon Watson, a twenty-nine-year-old librarian archivist soon to be a victim of budget cuts:

Perched on the bluff’s edge, the house is in danger. Last night’s storm tore land and churned water, littering the beach with bottles, seaweed, and horseshoe crab carapaces. The place where I’ve spent my entire life is unlikely to survive the fall season. The Long Island Sound is peppered with the remains of homes and lifetimes, all ground to sand in its greedy maw. It is a hunger.

Hungry for more? More keeps coming. This is not one of those novels with openers that hook us, then flattens. I loved the crisp prose – opening chapters, sentences, word-by-word. (Exception: Simon’s constantly swearing, tarot-card-addicted, rough sister. Named after the plane that dropped the atom bomb, Enola feels explosive.)

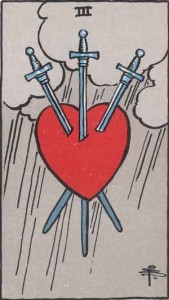

I couldn’t put Erika Swyler’s debut novel down. A testament to how much I loved her taut, vivid prose because I shun away from mystical themes. Nor am I nostalgic for circuses or carnivals. Certainly not the freak shows. This is not your Greatest Show on Earth memories of slapstick clowns and fluffy cotton-candy, or Ferris wheels and skeeball carnival games. This is a darker underbelly of circus acts, where truth is an illusion. I’d never even heard of the term “cartomancy,” nor interested in tarot cards dating back centuries. The Waite deck, alluded to, might be the type passed down through the generations that keeps popping up, especially the ominous ones like the Three of Swords depicting a heart with three daggers piercing it. The symbolism of these cards plays out as the novel alternates between circuses past, Simon’s disquieting present and his near-future fears – which eventually converge.

The present revolves around the burden Simon has carried since eighteen. He’s been Enola’s surrogate father, after their mermaid circus performing mother, Paulina, a dark-haired beauty, drowned young, on July 24th. Their grief-stricken father essentially stopped living: stopped nurturing his children and completely ignored their circa 1700s historic house, so badly weathered by the waters today it’s literally falling apart. Then, he died of a heart attack. From heartache? Did he realize his wife’s family was troubled? Questions you’ll start wondering about as the novel unfolds.

It kicks off when Simon receives an antiquated book from a cheerful, elderly bookseller in Ohio with a circus-sounding name, Churchwarry. The rare book, adorned with eerie photographs illustrated by the author (an interesting addition) was part of a lot he speculated on at an auction. Simon’s grandmother’s name, Verona Bonn, was inscribed in the book, which is how it found its way to Simon.

There’s a hypnotic rhythm to the prose as the researcher obsessed Simon (who admits he’s better suited for reference work than people) obsessively researches the enigma of his grandmother’s attribution. He discovers she too was a circus mermaid who drowned young, on the same day his mother did.

Simon is like us: “I’m not a believer in curses. I like facts.” So he delves into circus history back to 1816 uncovering too many women in his family drowned young. All on the same fateful day. All circus mermaid acts. Seems his family has a superhuman ability to hold their breath underwater for incredibly long amounts of time. The skill (gift? curse?) lives on in Enola, and in Simon, the lone male. Paulina’s swimming-lesson voice haunts Simon. She schooled Simon and Enola to do the impossible.

As far-fetched as drowning mermaids over many generations in one family may sound, reference to the Flying Wallendas “dating back four hundred years, with a string of falls and accidents tragic enough to be called a curse” makes the family’s fate and Simon’s trepidation a similar fate will befall Enola seem plausible enough.

Enola, who Simon tells us is “not easy,” is easy to worry about. She’s chosen the same surreal circus path, but not as a mermaid. Prescient? She’s a tarot-card clairvoyant with a traveling carnival. Early on, she phones Simon, desperate sounding. She’s coming home for a long-overdue visit – abandonment a theme – accompanied by her tattooed boyfriend, Doyle. Another human freak act: Electricity Boy at the carnival. Doyle’s tenderness with Enola, and by extension, her brother, makes him likable actually.

Enola is aghast at the neglect of the house. Of course, Simon can’t afford the exorbitant costs to fix it, especially now that he’s jobless but he also can’t bear to let it go. He’s acknowledged he’s also “not easy,” but his emotional ties to his childhood home touch us. His neighbor, Frank McAvoy, father-like, can cover expenses. He’s fixated on this house, misses its occupants. His daughter, Alice, red-haired and freckled-faced, is a programmer at the same library as Simon. The two grew up together on this lovely and mysterious expanse on the Long Island Sound. Their friendship gets tangled up as Simon digs deeper into the precious book curiously in his possession.

“Portable Magic and Miracles” is a circus log meticulously maintained by a flamboyant, richly imaginative, profiteering circus-master with a flair for showmanship and a commanding voice. It details the comings and goings in northern and southern cities in America of his otherworldly circus menagerie.

“Never had there been such a man as Hermelius Peabody and he was fond of saying so,” boasts the journal’s keeper. Of all the weird acts he concocted, controlled, and chronicled most alive are the witchlike fortune-teller Madame Ryzhkova because her tarot cards offer a mute savage boy, Amos, a miraculous way to communicate. Peabody found him; turned him into the caged Wild Boy act. “We’ve all got to be somebody,” Peabody proclaims. He’s pecuniary but he has a heart, caring for Amos outside of the show like a son. Thankfully, the tarot-card diviner has a better idea. She mentors the mute boy as her trusted apprentice, teaching the double meaning of the cards (“Fool is fool because of blind happiness. He does not see misfortune.”) She cautions: “the seer is a blade. Too much softness dulls the mind. Silks and curtains are for guests.”

Was the fictional Peabody inspired by the real British circus manager Philip Astley? His name is casually dropped. There’s similarities: both had a large frame, booming voices, exceptional business acumen, and Astley was thought to be the originator of freaky acts. (Not all in Peabody’s circus is dark. There’s Benno, the strongman, “taught to watch for gentle souls”; and a miniature horse, Sugar Snip, who stands for kindness.)

Peabody’s writings drive home that no matter how weird or wacky or folkloric, circus performers have feelings too. The mute boy longs for a mermaid named Evangeline who taught him that “a smile did not always mean happiness, crying might mean sadness or joy, and that women could be much comforted by an embrace.” Amos also cares for the Russian psychic who also taught him how to live. The two women don’t mix well. “All folktales have a price.”

Simon figures out there’s a price to his fact-finding too. As the clock ticks, there’s revelations and a tense ending. Much to ponder but one thing you won’t need to speculate on: “Books have a way of causing ripples.”

Lorraine