Believing the unbelievable (Connecticut shoreline and Ithaca, New York; sometime after the late 90s): If you told me I’d be raving about a paranormal novel in which the central character – Martha Mary – sees the dead, I wouldn’t believe you.

Believing the unbelievable (Connecticut shoreline and Ithaca, New York; sometime after the late 90s): If you told me I’d be raving about a paranormal novel in which the central character – Martha Mary – sees the dead, I wouldn’t believe you.

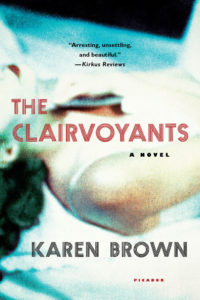

The Clairvoyants is psychological intrigue that eclipses abnormal mysteries of the psyche to significant supernatural realms. With terrific prose, Karen Brown manages to pull off her parapsychological story so believably, blending past and present, truth versus lies or something much stranger. Stranger than the two unsolved deaths that haunt this tale of foresaken souls, living and dead.

A 19th century quote by Charles Webster Leadbetter, a clairvoyant and leader of the theosophy movement, introduces the surreal:

“And he will find them divisible into two great classes – those whom we call the living, and those others, most of them infinitely more alive, whom we so foolishly misname the dead.”

From the start, I wanted a psychic’s dictionary! (Plenty online). While theosophists have faith in otherworldly dimensions grounded in kindness, peacefulness, non-violence, the characters in this novel are not at peace. Far from it.

A better resource would be to sit in one of the author’s creative writing classes (she teaches at the University of South Florida) to hear her speak about the techniques she uses to create chilling psychic suspense: gothic elements and nature to heighten the somber mood, to plunge emotional depths and complexities.

To help set the mournful tone, you might want to listen to a piece of beautifully sad music – the Elgar cello – Martha hears at the ending. Written by British composer Edgar Elger after WWI, it’s gorgeously composed yet full of pain. Symbolic of the overall feel to the novel.

Do you believe in ghosts? Extrasensory perceptions (ESP) as in seeing ghostly visions of the dead? Do you think someone who sees past events and haunted places is mentally ill? Or, could the unexplainable be possibly explained?

Karen Brown explores the possibility that if a person is acutely and chronically stressed, desperately lonely, craving love and affection, and there’s a strong genetic component to being taken in by clairvoyance, it’s possible that individual, like our narrator Martha, could experience weird phenomena outside the normal senses. To further her message, Martha’s younger (only by a year) sister Del had a psychotic break in her teens resulting in psychiatric hospitalization, then moved to assisted living, around the time a fifteen-year boy, David Pinney, was murdered. His death also marks the onslaught of Martha’s recurring ghost spirits, torturing her soul.

Eleven universities from around the world once or still study paranormal phenomena. Might there be a shred of something to all of this?

Brown sets the supernatural stage in the opening pages by telling us about Martha’s great-grandfather’s occult manuals she uncovered in a barn on the family’s Connecticut property by the Long Island Sound.The titles of the manuals tip us off: Psychometry, Clairvoyance, and Thought-Transference and Psychism, Ghostology, and the Astral Plane. So do his marginal notes asking:

“What is the ethereal double? Who travels on the astral plane? How does the clairvoyant receive messages from the dead?”

Another early indicator that we’re in for something different is the Connecticut acreage was purchased in the 1890s, a timeframe that aligns to the theosophical movement, and that a portion was leased to a clairvoyant group that keeps reappearing: the Spiritualists by the Sea. They built a temple, and when Martha and Del were growing up the spiritualists lived in colorful cottages and played eerie organ music.

Martha and Del are peculiar characters, but they’re not the only ones. Their mother is buttoned-up, a cold fish who works at a prison store; their parents are divorced and their father is out of the picture; and the two girls are alienated from their much older sisters. Martha was expected to watch over impulsive, promiscuous, seductive Del, a love-hate relationship of resentment, jealousy, isolation. Feelings of abandonment loom large.

Before Del had her mental breakdown, the two sisters’ idea of play, always instigated by Del, was fortunetelling, conducting seances. “Lying was what we did best together,” says Martha, who seems an honest broker until you’re not so sure she is. You’re led to believe Martha is the stronger of the two, until things shift and then you’re not so sure about that too. What you do know is both sisters are coming-of-age psychologically disturbed, awfully damaged.

Another abnormal character is William Bell, whom Martha meets when she goes to Cornell University and gets deeply entangled with him. Martha is, not surprisingly, drawn to abandoned places, so she focuses her studies on photographing abandoned sites. William teaches photography at the college, obsessed with photographing vulnerable people. When revealed what that entails, you’ll get the creeps. At first, Martha’s loneliness fits William, an only child whose parents are gone, so she puts up with his oddities, evasiveness, and disappearances, telling herself this is what it means to be consumed by one’s art. Don’t be fooled!

Martha hoped when she left Connecticut she’d also leave behind her ghostly apparitions, which begin on the first line of chapter one. Only seven, she claims to have seen her great aunt whom she’s named after. Next comes David Pinney’s persistent ghost, which is why she’s“doubtful that freedom would ever really be mine.” Martha’s demons don’t go away. As soon as she arrives at Cornell, she glimpses the second unsolved death – the ghost of Mary Rae Swindel – central to the plot.

“I could distinguish them from the living by the way they stared at me, their expressions anxious and filled with longing, as if there appearances had been conjured by the despair of a lost love.”

The author very effectively and consistently uses secluded landscapes, abandoned places, and gloomy weather to achieve a spooky effect. (“The elm cast shadows on my white plaster wall, and its branches, sheathed in ice, clicked together like bones.”) She knows these areas from personal experiences having grown up in Connecticut and graduated from Cornell in Ithaca, New York. Now living in Florida, none of its sunshine warms this ominous story.

While there are two warmer characters, they’ve got problems too. One is a painter, Anne, friends with William; the other Martha’s landlord, Geoff, a British fellow characterized as a “Heathcliff type,” a nod to the American Gothic classic Wuthering Heights.

It’s not just the thermometer that registers chilly but the emotional one. Lots of sex, characters searching for warmth, but their acts have nothing to do with love and grow increasingly perverse.

Del’s time at a psychiatric hospital wasn’t pure fiction. Brown tells us the beautiful film star, Gene Tierney, reported to have had seventeen breakdowns in the forties and fifties, was hospitalized there too, enduring electroshock treatments like Del did decades later.

When it’s hard to distinguish reality you can’t help but wonder if other references to key places were inspired by real ones. The acknowledgements provide some answers. The most revealing reference, though, is the course Martha is taking on Women and Grief.

I’m still not a believer, but this was one heck of a believable tale.

Lorraine