The unbreakable bond between two siblings arising from a broken house (Elkins Park, Pennsylvania dominates, 1946 – 80s): Admired, award-winning, bestselling author and co-owner of Parnassus Books in Nashville, Ann Patchett, is a household name to millions. Whenever she comes out with a new book, the literary world is abuzz. Her eighth novel, The Dutch House, is no exception.

Patchett was singled out in Time magazine’s 100 Most Influential People in 2012 for her “wisdom, generosity and courage” and “moral code”. All on full display in her new novel, in its heart-to-heart, astute prose and principled, selfless central character, Maeve.

At ten, Maeve mothered her three-year-old brother Danny, and never stopped. Their mother abandoned them, without a word. Trauma worsened by an extraordinarily self-centered, apathetic father, absent even when he was present at the dutch house, named for its prior owners, a Dutch couple, the VanHoebeeks.

The grandiose mansion stuck out like a sore thumb in an everyday suburban neighborhood outside of Philadelphia, more “Versailles than Eastern Pennsylvania.” A see-through design – glass entranceway at the front and back – let’s us imagine how anxious, discomforted, exposed one might feel in a house like that – precisely intended. Sister and brother spent their formative childhood years there, until they moved out, Maeve first, then Danny.

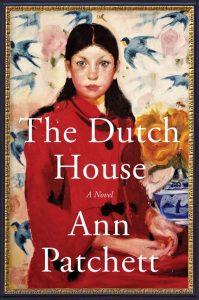

Initially you may be unsure whose penetrating image is featured on the cover. That’s because inside the opulent entrance hall hang two portraits of the former occupants painted in the same artistic style as the cover. “Rendered with Dutch exactitude and a distinctly Dutch understanding of light,” we think perhaps it’s their daughter? Whoever it is, the arresting image feels iconic, reminiscent of the Dutch Golden Age. You’ll soon figure out the image is Maeve, making it one of the best covers for a novel for what it reveals and portends.

Inside, the paintings creepily hover over the first floor. In fact, all the former belongings hadn’t been cleared out, the couple died leaving everything behind. But why not remove strangers’ things, personalize the house, make it your own home? Palatial marble and fancy chandeliers will never transform this house into a home.

Maeve is on the cover since she looms large in Danny’s eyes. He’s our storyteller, the sibling who keeps revisiting and questioning the veracity of his early childhood memories growing up in that “depressing enterprise.” His narration, the author’s literary weapon, chronicles the siblings’ life in clear, flowing, realistic, down-to-earth recounting. In stark contrast to the pretentious, shrouded estate.

“Mothers were the measure of security,” Danny says, as he goes back and forth in time with Maeve about his recollections, questioning whether anyone can be objective about their past. Especially with a father who “didn’t tell us anything,” who matter-of-factly managed to inform them their mother went to India, but that’s all. Didn’t give a hoot how alarming a mother’s disappearance would be, or how that impacted them when she never returned.

Danny’s narrations feel like natural, intimate conversations he’s having with us – in Maeve’s car. Parked across the street from that oppressive house, this setting becomes a ritual, as they return to it over and over again through the decades, rehashing, dissecting perceptions of the origins of their disquietude. An obsession that plays out through various stages of life: coming-of-age, college, career and marriage choices, into mid-life. Relayed when they’re both outsiders, even when Danny lives in New York. It’s Maeve who doesn’t alter her geographical world much.

The magnetic strength of the novel is found in Danny’s poignant, bewildered, regretful, relatable conversations; in lengthy, sweeping paragraphs, sometimes running more than a page. Chapters longer than we typically read that swallow us up the way life does.

Maeve’s cover painting marks a major turning point in the siblings’ lives – when their mother deserted them. Like art lovers and critics who analyze an artist’s intentions, we do the same with Maeve’s image as the siblings and novel develop, as Danny gains deeper insight and so do we. When we examine Maeve’s blue eyes, we see how watery they are, on the verge of crying. We observe how awkwardly her hands are resting. How painfully sad she appears. This is what it looks like when a child’s world is frozen. Why the siblings clung to each other, and never let go.

Danny is devoted to Maeve above anyone else, and she to him, to both of their detriments. Loyalty is an overriding theme, carried to extremes. The two show us how far people can go to protect someone they love more than themselves.

Three household staff did watch over them – a housekeeper, cook, and another housemaid who came before them. They loved them as best they could, but there’s no substitute for a mother, or a substitute mother whose blood runs through yours.

The novel opens after WWII, when Danny, eight, is reading in fifteen-year-old Maeve’s upstairs bedroom on a window seat hidden behind drapes. Sandy, the housekeeper, disturbs the peace announcing their father beckons Danny (not Maeve) downstairs to meet a friend of his, Andrea, an early sign of the unraveling, noting their father “didn’t have friends.” By page six, Danny tells us the two married, though that earth-shattering event didn’t happen until later, slowly burning through Danny’s alternating-in-time recollections of a future, wicked stepmother who “lingered like a virus.”

To emphasize how lost sister and brother were Patchett doesn’t even reveal the father’s name until page 96. Emotionally detached from them, and later to his young stepdaughters, Norma and Bright. A tumultuous, dysfunctional, blended family that never blends.

Considered a companion to the author’s previous novel, Commonwealth, also about complicated family relationships arising from divorces and intermarriages, the author is wonderfully forthright as she is in her books (see interview), confiding this is familiar personal territory. She then surprises by saying writing, rewriting the novel felt “like burning a cake.” Yet nothing feels wasted as the prose is so assured and humanly plotted we feel we know Danny and Maeve, or someone like them, if only we were privy to their inner thoughts and emotions over decades like Danny candidly shares.

Maeve, like the Time quote, marches to her own moral compass. Danny laments she didn’t use her math-whiz skills to her potential, having failed to encourage her to do so. Instead, she settled for an uncomplicated life, saving her valiant strength (her health compromised by diabetes) to always be there for Danny. Maeve’s self-worth is wrapped up in feeling “indispensable” to Danny, and to a kind, empathetic employer. Can you blame her?

Maeve, though, is relentless at pushing Danny; he, like a dutiful son, abides by her wishes against his own. As hard as it is for a parent to let go, it’s equally hard for that dependent child too, even when they have their own family. That havoc is here too.

Politics is also very much alive, depicting the damage an exclusive fixation on wealth inflicts. The much-disliked father only cares about growing his real-estate business, and grooming Danny to takeover. Otherwise, he’s abnormally disinterested, insensitive, empty. (Distasteful Andrea focused on her own cunning motives.) It’s no coincidence the father’s profession and financial ambitions echo loudly, as “everything feels political to me these day,” says Patchett in another interview. Sending a resounding message about the true costs of wealth sought at any cost.

Tragically, Danny has been consumed trying to solve the mystery of his mother, and yet, in one particularly eye-opening revelation, realizes he’s also spent “every minute of his life” worrying about Maeve, his heroine.

Heroines are meant to inspire us and can break our hearts. That’s what Ann Patchett pulls off. Time and time again.

Lorraine