The Price of Artistic Genius – A Psychological Novel (Iowa, New York; two contemporary decades in the maturation of an avant-garde filmmaker): Does an artist – in this case an independent filmmaker – have a “responsibility to make the best movies possible” even at the expense of others? How far should an obsession with making great art go?

The Price of Artistic Genius – A Psychological Novel (Iowa, New York; two contemporary decades in the maturation of an avant-garde filmmaker): Does an artist – in this case an independent filmmaker – have a “responsibility to make the best movies possible” even at the expense of others? How far should an obsession with making great art go?

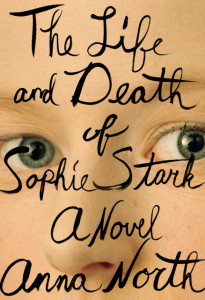

These are some thought-provoking questions The Life and Death of Sophie Stark raises again and again, forebodingly, until you find yourself feeling like one of the characters expresses (and all experience): Sophie gets “under my skin.” As she’s meant to. The more black-hearted, the more we try to figure her out, creating a riveting psychological drama. Anna North has conceived of an extremely provocative, intense, dysfunctional protagonist, ripe for both a case study in an abnormal psychology class and a filmmaking discussion on personal ethics and professional integrity.

North’s debut novel is terrifically structured. Told mostly through the voices of those who knew, loved, and were badly hurt by Sophie – lonely voices of their titular chapters – you’ll find yourself, like them, trying very hard to understand Sophie but coming away short. She’s too full of paradoxes, so avoid labeling her. To her credit, North does not, for she intends for us to mull over Sophie through these exploited voices.

What you can count on is Sophie confounding you. She can’t be pigeon holed as flat-out depressed even though her emotional presence is woefully flat, cold, bare, seemingly heartless, as she doesn’t lack interest in everything: Sophie cares about photography and cinematography.

But she’s a loner even in the midst of relationships she’s involved with: younger brother (Robbie); lesbian lover and actress (Allison); musician husband (Jacob); movie producer (George). They are the voices that fill most of the narrative.

Intermingled with these heartsick voices are the astute comments of an unconventional film critic, Ben Martin. He’s not anywhere as far out as Sophie, but he burns with idolism following Sophie’s filmmaking career – her rise from high school to college in Iowa, to a fellowship in New York City, a brief episode in Hollywood and then back to the city. Of all the voices, he’s my standout, for these reasons:

- The clever design of his journalistic career, almost paralleling Sophie’s growth. We see his seasoning through the sophistication of the media in which his critiques appear: from high school paper to local newspaper to an online site to a magazine to mainstream news.

- He’s the wise validator of our interpretations of Sophie. Her influence on him as a filmmaker notwithstanding (Sophie “made me want to watch movies for a living”), he too can’t “fully understood her as a director or as a human being.”

- Prose-wise his voice is the most distinct, lyrical, insightful, and my preference – without vulgarity.

- As a “former unusual kid myself,” Ben can put himself inside Sophie’s head better than the others. He’s not the only character who recognizes her “genius,” but when he pronounces her artistic exceptionality we accept it since studying films is his profession. His analysis of the impact of genius on others offers an interesting perspective for considering why all the characters let Sophie swallow them:

“It’s one of the perks of genius that you can be difficult or even impossible and not only escape censure but enjoy praise and the careful ministrations of others. This is a source of especial jealousy for those of us who are merely difficult without the benefit of genius.”

While the other voices – narrators – may sound similar, collectively they add to our deepening appreciation of Sophie’s unique talent, and to the damage she wreaked on the fragile lives of those who cared about her and respected her as an artist. They may seem to be eerily drawn to Sophie for their respective reasons, but you’ll find a commonality of heartrending themes: extreme loneliness, hunger for attention, longing to feel or become special. Sophie flatters them by noticing them, listening to them, filming them, but was hers just an agenda all along? Did she use trusting people like props, doing whatever it took to startle and capture the “sad fumbling of human love”?

Which means this is a sad novel. The characters are sad, their stories are sad, and Sophie is the saddest of all since the only way she really functions in the world is behind the lens of a camera. We hear about her fascination with picture-taking in elementary and high school. Her filmmaking career takes off in college where she focuses on how people move. Her first foray was a short documentary, Daniel, a borderline stalking endeavor of a popular basketball player with a jealousy-crazed girlfriend. Other films follow, her talent developing, but one thing that doesn’t change is her intensity. She’s so fiery everyone remarks her skin was “hot.”

It’s tempting to tell you about each of these characters, their entanglements with Sophie and how sorely she wronged them. But I’d rather highlight some of Sophie’s paradoxes so you see the emotional range of the author’s storytelling.

THE PARADOXES OF SOPHIE STARK (she’s even taken her name from someone else, a photographer):

- Physically small (compared to a 12-year-old boy at 23), but her artistic power is perceived as big.

- Confident and bossy in her moviemaking, but hers is a “scary joy,” seeming to stem from an enormous fear of failure.

- “Conveys deep emotion by means not generally considered emotional.”

- Acts like she doesn’t care what people think of her/ haunted by what people think of her films.

- Plain, casual speech, yet she’s complex, almost beyond understanding.

- “For someone who didn’t understand people, she was good at getting right to what would hurt me.”

- Unable to discuss her feelings. Her movies are the only way she shows her feelings.

- Appears oblivious to others/“hyperaware” of others.

- Films display mastery/films are flawed.

- People are jealous of her/people feel sorry for her.

- Makes movies about people/her movies take her further and further away from people.

- Moviegoers aren’t sure if her movies are “a good dream” or a “nightmare.” Similar to readers wondering if Sophie’s story will turn out good or bad.

The effect of Sophie’s special brand of visual imagery is “getting down to the ‘soft core’ of people.” In remarking that her “eyes never blink,” Ben wonders if “maybe she’s able to see a wider angle that most people can,” as he writes reverently about her mastering:

“a particular wide shot, with the camera placed slightly above the actors and giving a nearly 180-degree panorama … less interested in reproducing life than in transcending it, showing us what it would look like if we were able to step back beyond the bounds of what’s humanly possible.”

Then there’s the aging movie producer, George, desperate for a blockbuster win, hoping Sophie is the answer to his dreams. Like Ben, he makes the same observation about her: “like an alien had come down and filmed humans and shown us what we were like so much more honestly than any other human could.”

George even goes so far as to counsel Sophie that it doesn’t matter if her process of filmmaking burns others, for those feelings don’t matter as much or won’t last. What endures are her movies. That’s what she’ll be remembered for.

Yet given the emotional damage she leaves behind, also long-lasting, let’s not be so quick to tout the ends really do justify the means. That’s too easy, and Sophie Stark isn’t easy at all.

Lorraine