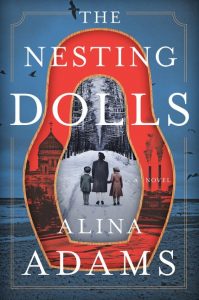

The trauma of Russian Jewish oppression passed down five generations (Odessa, Ukraine and a Siberian labor camp, USSR, 1931 to 1975; Brighton Beach, Brooklyn, 2019): The catchy title of Russian-American Alina Adams’ sweeping historical family tale comes from the brightly painted, wooden Russian female dolls ranging in size from larger to smaller, each fitting inside another. Representing motherhood, they also represent four of the five Russian Jewish female characters, all mothers from different generations of a single family, in the Nesting Dolls.

The doll/character who doesn’t fit comfortably is the smallest/youngest one: Zoe, the protagonist, twenty-something-ish, single, childless. She’s not supposed to fit easily as she’s the modern-day character, half-in and half-out, having trouble fitting in with the Old World and a Russian-born-in-America’s new one. The older women’s stories help explain why.

Could anyone other than a gifted writer born in Odessa, Ukraine – like three of the five generations of women in Adams’ novel – who immigrated with her family to America in the 1970s when a wave of Russian Jews were able to escape their Communist “prison country” – be able to craft such an emotionally authentic Russian Jewish historical novel? By the time you reach the final page “About the Author,” you’re likely to think maybe no one could.

By definition, a novel that chronicles a family over a period in time is a sub-genre of fiction called a family saga. The Nesting Dolls easily fits that descriptor. Chronicling the Russian Jewish experience reaches far beyond that.

A whip-smart, four-page Prologue introduces four generations (the first generation is no longer alive). If your brain is like mine, you may find the familial names/relationships a bit confusing. Please don’t put this book down, thinking you’ll return to it when your mind is clearer. Because as soon as the novel opens in 1931 with Daria’s incredible Odessa-to-Siberian labor camp journey, you’ll be mesmerized. Reading what it was like to have “no rights, only obligations” will be painfully clear.

One more caveat: please don’t think all five generational stories are as deathlike and soulless as Daria’s, although the three women born in Odessa had “lived in the dread.” Rather, it’s how the scars from their experiences got passed down to Zoe, that provoke the question, Can you ever escape the trauma of persecution?

To get you past the brilliant, enigmatic Prologue that you’ll return to some 250 pages later when it makes perfect sense, below are the characters’ names and relationships to Zoe, because that’s how the reader must understand them.

First Generation Daria: Zoe’s great-great grandmother. Born Dvora Kaganovitch. Hers is the longest story. Chapter 1 opens with Daria just married to Edward Gordon, a famous pianist “too privileged, too genteel” for the bleak, harsh Soviet system. Traveling the world to give concerts made him a suspect, an enemy of the State. Truth is all you had to do was act like an “individual above the collective” to be viewed as a traitor, especially if you were a Jew. The newlyweds lived with Edward’s father and were watched over by a giant of a man, Adam. There’s even a Russian word for him: dvornik. He watches their “comings and goings” at their “crumbling” apartment building. Adam is the reason Daria ends up in the frozen tundra of Siberia.

Kommunalka is Russian for communal living. Four generations of these women lived that way. No privacy, and always feeling like someone will turn them into the authorities. Zoe is the outlier again, the only one living alone. But she stays close to the other three generations living together in Brighton Beach, a Brooklyn enclave where Russian Jews immigrated to.

Second Generation Alyssa: Zoe’s great-grandmother, in her eighties. Also referred to as Balissa and Baba. Zoe’s story kicks off in the Prologue in the apartment the three women share, with an ignored man, Deda, Alyssa’s husband. Zoe’s there to help pull off Baba’s forty-fifth anniversary party, but Baba doesn’t want one. Her daughter, Julia, Zoe’s mother who lives with them, insists they do. No one knows why Baba is adamantly against it. Her secret unravels for us. At the end, at the party, glimpsed by everyone who quietly gasp.

The party isn’t the only thing Baba is negative about. It’s everything, because she was with Daria in that brutal labor camp. The product of “terrible child-rearing,” she mostly blames the “entire political system of the USSR.” Today, this survivor is a silent, bitter soul, but through it all she’s maintained her dignity.

Third Generation Natasha: Alyssa’s daughter. Zoe’s grandmother or Baba. Born Natalia Nikolayevna. Blame is carried down: she blames her mother for doing nothing about “a genocidal regime.” “The Jewish problem” in the USSR meant she was denied entry into the university to study math, which she deserved. She shared an apartment with another family: Boris’. He’s accepting and focused on “commonplace things,” the complete opposite of Natasha, who inherits her mother’s bitterness and yearns to do something meaningful with her life. What could be more meaningful, and dangerous, than getting mixed up with a mission “to expose how the Soviet system brutalizes its people”?

Fourth Generation Julia: Zoe’s mother. Divorced. A “soft-spoken, conflict-adverse peacemaker,” unlike Julia’s mother Natasha.

Fifth Generation Zoe: Also called Zoya. Born Zoyenka. Confused about many things. Doesn’t want to dwell in the past. She’s the one who wants what we want: happiness and joy, in a career and romance, but that conflicts with what her family believes is best. An example of how this doll/ character is stuck in the in-between: “When I date American guys, I feel like I don’t fit in with them, and when I date Russian guys, I feel like they don’t fit in with me.”

There are many ways to describe the novel. One is that it’s a clarion call to activism, reminding us that “change can come only through action.”

According to the Jewish Telegraphic Agency, it’s rare to uncover family records of Russian Jews as they simply don’t “exist”. So another way to describe what Alina Adams has most notably done is uncover one family’s record that feels awfully true.

Lorraine