An author who also writes poetry magnifies the beauty of an unlikely friendship between young and old that changes their lives (from Durham, northeast England, south to Robin Hood’s Bay, North Yorkshire; WWII aftermath, 1946): If ever there was a year when reading collectively saved the luckiest of us, 2020 is it. So it’s especially fitting that this final post of the year has one of the most satisfying closures for two very different characters – age, experience, personality, gender, social class – and for readers.

The Offing by British award-winning writer Benjamin Myers is only the second of his seven novels published in the US. A beautiful, wise, and poetic novel that looks back on one life-changing summer when a friendship – between sixteen-year-old Robert Appleyard and Dulcie Piper, nearing sixty – blossomed, taking the young man under her wings when she needed him as much as he needed her. But she doesn’t let on that she’s terribly lonely, and that buried underneath her zest for life is a terrible sadness.

Robert narrates this poignant story, looking back at their relationship when he’s now old, to a summer when he was coming-of-age and Dulcie changed the trajectory of his life. On page three, he tells us, “I cling to poetry as I cling to life,” clueing us in how poetry made all the difference. Actually, the first clue to the importance of poetry in the novel, and for Myers, is when he introduces the story with a poem by a 19th century British poet, John Clare, a “quintessential romantic poet.” Clare, like young Robert, came from a poor family, loved nature, and was a romantic “daydreamer.” Clare resurfaces later when Dulcie introduces Robert to poetry.

When Robert tells Dulcie poetry is not for “people like me” – “coal folk” – she replies, “trust me when I say that everything you’ve felt has been experienced by another human being,” triggering her quest to find him “poetry you can relate to” from her extensive library. Poetry is among the many things he discovers at an uncertain age during an “age of uncertainty.” WWII may have ended, but food was still being rationed and people were downtrodden by the enormity of their losses. But Robert is restless, and also aware “life was out there, ready and waiting to be eaten in greedy gulps.”

The Offing is also fitting to close out the year with for a blog passionate about enchanted prose by an author who lets us know in the Acknowledgments that he has a “passion for the written word,” so much so he literally wrote the novel longhand in libraries. The novel is full of poetic writing since Meyers is a poet with several poetry collections to his name. A diverse writer and journalist, he’s also penned a non-fiction book, Under the Rock: The Poetry of Place, which I’d love to read since it likely contains the same marvelous, atmospheric nature writing and strong sense of place this novel has.

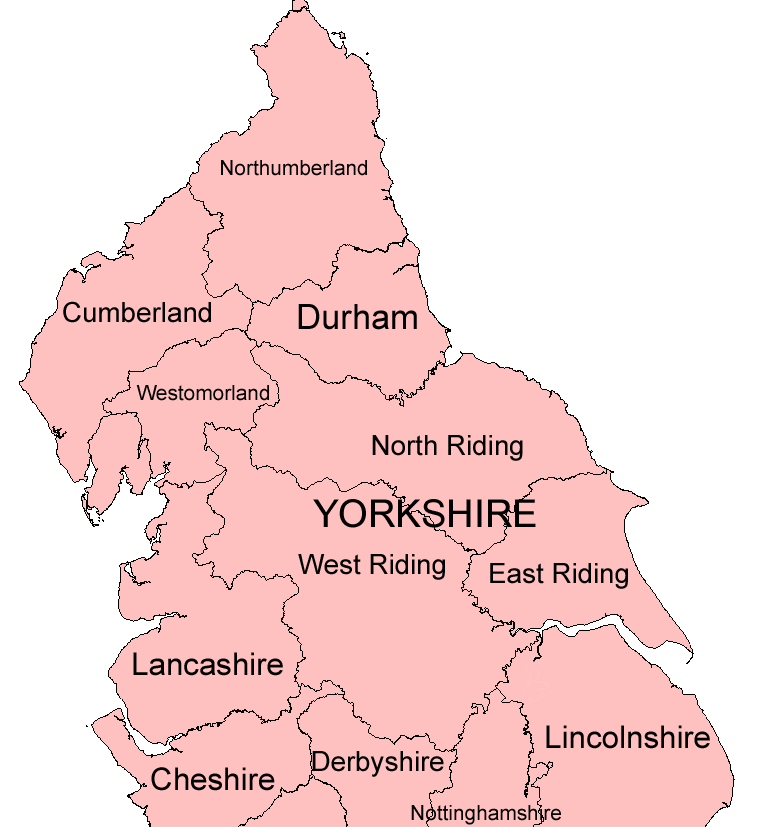

When Robert sets off from Durham, England (where the author is from), he’s ripe for escaping this northern region tied to Britain’s long history of coal mining. His father is a coal-miner, expects him to follow in his footsteps.

By MRSC (CC BY-SA 3.0) via Wikimedia Commons

Robert’s background resonates with all people whose dreams and desires have been stuck in a cycle of repression and poverty without the resources to break free. Although he’s not an activist, Robert wants a freer life, one not limited in opportunities. Dulcie shows him a way, feeding his hunger, physically, sensually, and emotionally, because of who she is and what she offers.

Roberts dreams of the sea. The novel indicates Dulcie’s seaside village is in North Yorkshire. In a Guardian article, the idyllic village is apparently Robin Hood’s Bay (suggest you save for later as this link has spoilers). The contrast between his bleak homeland and the seaside landscape awakens him. Not nearly as much as Dulcie stirs his senses and spirit.

By Snapshots Of The Past (CC BY-SA 2.0) via Wikimedia Commons

When Robert sets off by foot all he has is a backpack and a deep appreciation for nature and wildness. The southerly path he wanders along takes him through a mystical, lush landscape of rivers, moors, and bright green valleys. So much “newness of the unfamiliar was intoxicating.” Since England is a country with a “right to roam,” he ends up crossing Dulcie’s property, which includes a well-lived in stone cottage, an abandoned shed, and an untamed, abundant garden that’s so overgrown it blocks the view of the water. Unimaginable to him.

Robert had no intention of lingering long at Dulcie’s home, but she’s a force to be reckoned with, graciously and convincingly initially offering him nettle tea in her garden. The first of much wine and lobster, and other overindulgences new to him. With her “heroic tolerance for alcohol”; love of luxury foods, particularly lobster; drifting music; an endearing servant-like dog aptly named Butler; and eye-opening conversations, he ends up staying the entire season. In return, he takes care of her unwieldy garden and does other odd jobs, anything but coal mining. As he grows comfortable with this colorful woman’s provocative words and declarations, he engages more and becomes invested in their relationship. This was the summer when time was measured only by the “clock of green growth, and marked by the simple routine of working, eating, swimming, sleeping” – and discovering poetry that spoke to him. “Poetry had been one more way of keeping the working men and women in their place,” but “poems belong to the world.”

Dulcie has a lot to say. But if it weren’t for the deepening bond between the two, what she kept hidden would have remained a mystery. While we do learn about the profound secrecy, thanks to Robert’s perseverance and sensitivity, there’s still so much more we want to know about this extravagant, bohemian character who’s been friends with legendary writers, poets, artists, musicians. The lyrical writing makes it easy to envision a prequel to this novel about her full life pre-Robert. Cinematic, we can also envision a movie.

The alluring dialogue flows back and forth between these two opposites: Robert is the shy, innocent, respectful young man from “a place where brickwork was dyed black by soot-smoke and whose skies billowed with coke dust.” Dulcie is the one who lives in an iconic British village who “always chose pleasure at all costs.” “A cajoler,” “a prodder,” and a “perfect mentor,” she sees something idealistic, rebellious, and adventuresome in Robert that she embraced when she was young. Unorthodox, she rejects conventions, authority, control. “Let’s cock a snook to time, for time is just another set of self-imposed arbitrary boundaries designed to capture and control.” The fact that she possesses such “literary dexterity” is Myers’ way of showing us the power of prose. Robert and Dulcie also show us the power of mentoring.

“Travel is search for the self,” Dulcie confirms for Robert. Fortunate that she traveled the world, we take pleasure in armchair traveling at a time when our travel options are limited.

“Whatever happens, make sure you live,” she coaches. Just “believe in yourself, Robert. That’s all it takes.” If only it were that simple. But it’s a powerful, uplifting message sent during another uncertain historical time when life is also vividly precious.

Wishing you safe, happy holidays during the year that was so different than any other. Thanks for reading. See you in 2021.

Lorraine