Kinship with Montana’s wilderness, wildlife, Indigenous peoples, Native American art, and a rancher (Great Falls and the Northern Great Plains Highland Mountains region, Montana; 2004 – 2009): How do we know what will make us happy? In Elk Love, this means after your “body and soul” betrayed Lynne Spriggs O’Connor.

How do you move past a happy life that’s gone after losing your thirty-two-year-old wife and mother of your three sons without feeling you’re betraying her? Harrison O’Connor’s elephant in the room when he meets and is “intrigued” by the author who finds his boyish looks “arresting.”

She a Native American Art historian who got her doctoral degree at Columbia University in Manhattan, where she lived for ten years in her twenties and thirties and began her museum career. He an Angus cattle rancher living in an isolated valley of the last great ecologically important grasslands area in America. She from a citified culture, moving to Montana after seven years as a contemporary arts museum director in America’s South, Atlanta. Two lonely people from two widely different cultures.

Moving for a job leading a small contemporary arts museum in Montana, one of America’s least populated and diverse states, where the contemporary arts was a hard sell compared to the daily lives of a small Western Rocky Mountain town wasn’t her “heart’s calling.” The wild, vast, open landscape was.

Arriving in Montana in her early forties hoping for an “unfurling into beauty,” Lynne Spriggs had built a career studying, living among, advocating for, and inspired by “shapeshifters and self-taught artists” from a diversity of ethnic cultures – Indigenous peoples, African Americans, Mexicans. Having spent ten summers worth living on the Blackfeet Indian Reservation in Montana, where she’d discovered a “healing place,” the move landed her this time in a conflicting culture.

Soon after arriving in Great Falls, a museum board member suggests she visit Harrison, eyeing him as a potential new member and financial supporter they’re in need of. The museum is unnamed, which fits someone who’s a protector. Harrison is in his mid-fifties, thirteen years older when they meet. Elk Love tells five years of their story, but it’s more than that because Montana’s wilderness is her “magnet.”

Theirs is a slowly evolving romantic relationship. He’s grieving the death of his wife Moira; three years ago when the memoir starts. She’s dealing with protecting herself emotionally and with the challenges of cultural differences. Early on he tells her, “I don’t think I’ve ever met a Black person.” Imagine how disorienting that felt?

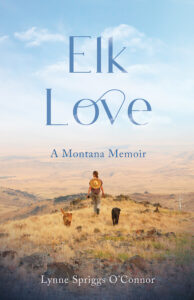

Elk Love is about seeking beauty, peace, friendship, and belongingness in Montana. About finding love in multiple and interconnected forms: Nature, animals, romantic love. It’s imbued with the Native American spirit of Elk Dreamers – symbols of the “healing medicine of love,” strength, endurance, and renewal. Qualities that resonate in this vividly detailed, true story written with grace and gorgeous nature writing.

There’s an elegance to the prose that reflects the author’s deep respect for the land. As far as memoirs go, this may be the only memoir reviewed in this space that pays tribute in the Acknowledgements to the “generous heartbeat of Mother Nature.” To the “autumn love songs of elk”; to the “welcome company of spirited gray-crowned rosy-finches”; to the “blossoms of colorful pasque flowers, mountain goldbanner, arrowleaf balsamroot.” To the “flowing waters of the Missouri River that have carried me each summer.” To the “unspeakable beauty of horses and cottonwoods, and to all that unites us.”

Twelve years in the making, grit, tenaciousness, and open-mindedness are on display, as well as faith and patience with a man who opens up and pulls back. A compassionate man who’ll risk anything for animals, but a man whose profound losses have caused him to believe life is “only endurance.” For a woman who meets him when “optimism is all that’s left of me,” her attraction to Harrison is tangled.

Over the years, the author spends more time with Harrison at his ranch rather than her small apartment in Great Falls. She falls in love with it and his eighteen horses and two pet English Setters her Golden Retriever Willow bound joyfully with through landscape where there was once “tens of millions of bison, then there are almost none.” You’ll see how the largest North American animal, nearly extinct, figures into this Great Plains Northern culture and art story.

Harrison kennels more of the regal and devoted bird dogs released to do what they’re bred to do: gently retrieve downed birds. Parts of the Western cowboy culture appeal to the author – the “comradery, horsemanship, and roping skills” – but she’s also shocked and dismayed at the “complicated relationship between what we revere and what we kill.” Reconciling the attraction to a man who’s both “hunter and a protector” is a powerful emotion poured into the prose.

It’s not just the killing of birds that disturbs. It’s the slaughter of big game – cow elk (females) and bull elk (males) especially. Two hundred roam Harrison’s world. How does the author handle the stark contrast with the healing power of “Elk Medicine,” a spiritual myth shared by the Plains Indigenous tribes, including the Blackfoot Nation?

She seeks to understand what Harrison loves and does. Learns how to hold and shoot a rifle aimed at tin cans and clay pigeons. Hunting not a match, but she does go along on bird hunts, whereas she’s well-suited to learning how to ride a horse and care for Harrison’s.

Dog lovers everywhere will delight in the companionship, comfort, and bond between humans and their beloved dogs. With the Missouri River running through Great Falls, the prose lets you picture the author’s and Willow’s pleasure taking walks along the river trails when she’s in town working and when she’s giving space to her roller coaster romance. “I feel drawn to Harrison, but “instinct warns me to hold back – to protect myself from being too vulnerable.”

The best thing Harrison does is connect Spriggs to his old friend Phyllis. “Luminous, like lemon zest.” One of those colorful, self-taught artists the arts historian has an affinity for, the two become fast dear friends, creating the sense of belonging yearned for. Phyllis has recently returned to Montana where she’s lived much of her life, like Harrison. Bursting with energy, creativity, and enthusiasm, she triggers the opening of moving boxes unopened for three years.

Hearts are at the center. Broken hearts, lonely hearts, hearts attached to Nature and animals. Hearts learning to trust. Harrison is fearless in the harshness of environmental elements, but it doesn’t come emotionally easily when a woman is falling in love with him he knows is so good for him.

As the romance builds, Harrison must work hard on changing how his heart responds to this healing woman he’s fallen in love with. The breakthrough comes when he shows he’s come a long way: “Have I told you how comforting and calming your hands are? Your touch always makes me feel better.”

Elk Love has the same feel-good effect.

Lorraine