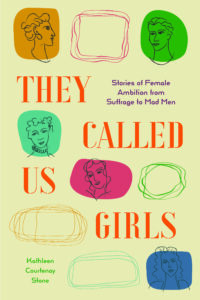

Women who defied the odds (1920s to 1970s, and the author’s personal journey): March is Women’s History Month, designated twenty years ago around the same time the National Women’s History Museum went online. I live in the DC area but didn’t know of this physical building, not to be confused with the National Museum of Women in the Arts, the only one of its kind. The reason I couldn’t recall visiting a first-of-its-kind women’s history museum is that it has yet to be realized. Firsts are symbolic of the stories in They Called Us Girls. The result of ten years of research in which Kathleen Courtenay Stone examines the lives of seven high-achieving women born before 1935, all of whom broke barriers with their own singular achievements.

Stone achieved her own success in a diverse range of legal positions, fascinated since she was a young girl about the influences on the careers of women who rose above societal expectations. The result may be a slim book (224 pages, with 34 illustrations), but it’s brimming with fascinating details – historical, societal, cultural. Strikingly relevant today, each story engaging, relatable, inspiring.

The seven women represent the “first wave” and “second wave” of the feminist movement: the Suffrage Movement culminating in women granted the right to vote in 1920; the second took fifty years later, beginning in the 1960s with Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique, reaching its heights in the 1970s civil rights movement with Gloria Steinem. The legendary feminist activist most associated with the era, co-founder of Ms. Magazine, was awarded the Medal of Freedom by President Obama and still going strong at eighty-seven years young, having just appeared in an event with the founder of Women for Women International, Zainab Salbi.

All the women Stone researched, interviewed, analyzed, and wrote compellingly about are Steinem’s age and older. The oldest she met with was ninety-six, the others in their early nineties and late eighties. Some she knew, some she didn’t. You’re not likely to have known or heard their names, remarkable given their achievements. But you’ll recognize their stories span the first half of the history of 20th century America:

- The First Wave Recedes: Dahlov Zorach Ipcar, Artist (b. 1917). The birth of the modern art movement, and how to become known as a female artist through illustrating (and writing) children’s picture books.

- Walking the Color Line: Muriel Petioni, Physician (b. 1914). Ellis Island immigration, Harlem Renaissance, the vital role of HBCUs (Historically Black Colleges). Dr. Petioni from Trinidad.

- A Unique Wartime Movement: Cordelia Dodson Hood, Intelligence Officer (b. 1913). WWII and the birth of the intelligence movement – the OSS (Office of Strategic Services), which became the CIA after the war.

- Peace and Polio: Martha Lipson Lepow, Physician (b. 1927). The game-changing medical discoveries of vaccines to fight polio, and antibiotics (penicillin).

- The Age of Sputnik: Mildred Spiewak Dresselhaus, Physicist, (b. 1930). The space race, nanotechnology, and the Depression. Another Obama recipient of the National Medal of Freedom.

- Time for Change: Frieda Garcia, Nonprofit Leader, (b. 1934). Desegregation, and the racial tensions between white and black and black versus Latino. From the Dominican Republic.

- The Second Wave Rises: Rya Weickert Zobel, Federal Judge (b. 1931). One of the fewer than 100 Federal Judges in the U. S. District Court. Also called the Article III judges because this special position is designated in the Constitution requiring Senate confirmation. Early Harvard Law School admission of women. Her start in the legal profession sounding a bit like RBG’s.

What sets this collection of mini-biographies also apart is that after each story, Stone writes a few memoiristic pages about her own journey she calls “Intermezzo.” They’re often connected to/inspired by the woman she just wrote about. As a partner in a law firm and senior counsel in a finance organization, she’s also clerked for a Federal judge including a case she defended in Rya Zobel’s courtroom.

These stories offer much food for thought. So many firsts but not because these women sought fame and fortune, but for their passion for whatever pursuit they loved and stuck with. Yes, she persists. All raised by families that believed in education not just for their sons but for their daughters.

The question of how much progress has been made in each of the professions represented begins with the first story of women as artists. Surprisingly, women haven’t made as much progress as perhaps we thought. Stone points us to a poignant article by a highly-regarded art historian in an art magazine, “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists? 50 Years Later,” to make that case. Ipcar went further in how she used cubism in her paintings of animals seen in more than forty of the children’s picture books she wrote and illustrated that brought her recognition. One of those books, Lobsterman, she remembered her parents reading to her brother.

The influences of parents digs deeper. The author cites a study that examined the influence of fathers on a girl’s development, part of a body of illuminating research that found if a father paid attention to his daughter he conveyed, directly and indirectly, “a sense that everything was possible.” This I can-do-anything-I-want attitude should be imprinted on all our children. In fact, it’s also a frequent ingredient in immigrants and minorities who instilled that same message. The profound “Father Effect” raises red alarms given that 15 million children are growing up in single households raised by mothers, and how many fathers have to work two jobs to help make ends meet. Many of the stories also show how hard a professional mother’s nurturing role was too, elevating the discussion of who cares for our children when it comes to the future of girls.

Not all of these women’s careers were specific to their father’s, but many were: Stone’s father was a lawyer; both Ipcar’s parents, Marguerite Thompson Zorach and William Zorach, were “noted members of the early modernist movement; Petioni’s father was a physician; so was Lepow’s.

The analysis of commonalities among these women is well-laid out by Stone in the Epilogue. Also included is a long list of resources she used in her research that’s blended in, coming across as highly accessible and entertaining.

While the lives of the women Stone chose to focus on all made a difference, there’s still a lot of progress to be made in today’s “fourth wave” of the feminist movement, spurred on by #MeToo. Inequality in the workplace is still seen in the gender gap, whether in opportunities, salaries, promotional opportunities, leadership responsibilities, and sexual discrimination. The “third wave” we’re also living now in terms of fighting for a woman’s right to her own body.

What also makes They Called Us Girls stand out is what Kathleen Stone wrote in an essay in 2019 for The Writer’s Chronicle when she was knee-deep in writing the book she describes as a “hybrid form” of the “group biography”:

“When writers add a personal layer to biography, they join the quest for meaning that began over a century ago, with artists and writers of the avant-garde.”

They Called Us Girls is a great way to celebrate the achievements of women for Women’s History Month, and throughout the year.

Lorraine