Dark shades of grey in an insular world of pretty pinks (Manhattan, and ballerina stories elsewhere; 2001-present day): Ballet is a supremely beautiful “visual art form.” Ballet is a supremely destructive aesthetic discipline. Clashing perspectives on an all-consuming artistic endeavor, and what happens when you’re no longer part of the ballet “cult.”

Alice Robb – a former “bunhead” who trained intensively for ten years at the most prestigious ballet school in America when she was young – the School of American Ballet (SAB) founded by Russian “creative genius” and choreographer George Balanchine (“Mr. B”) – has written an absorbing, frank, eye-opening memoir that’s not just about her early ballet life and the aftermath, but stories of other ballerinas, renowned and not.

Drawing its title from the authoritative words and philosophy of a ballet master who left his mark on the ballet world, “Don’t Think, Dear” is remarkably thought-provoking.

The desire to feel “special” overriding everything else, it’s no wonder that at thirty ballet is still etched in Robb’s “psyche and behavior.” Striving but not there yet to “break the ballet mindset,” it seems Robb isn’t the only one reckoning with the legacy of Mr. B (See: https://www.washingtonpost.com/theater-dance/2023/03/28/balanchine-city-ballet-ballet-podcast-/).

“The dream of being a ballerina begins with the dream of being beautiful.” What does it mean, though, to be made to feel you’re not “good enough”? To weigh yourself against everyone else? Competition so fierce it leaps off the pages.

Robb’s dream was to dance for the New York City Ballet (NYCB), one of the top ballet companies in the world, also founded by Balanchine. The SAB a training ground for the dream of becoming a “chosen one,” which meant having the perfect female body; “artistry and technique;” and the submissiveness Balanchine demanded of his girls.

Robb is a dreamer, starting with her first foray into her “post-ballet” writing life “Why Do We Dream”. In this deeply personal insider’s look at her unfulfilled ballet dreams, she also takes an outsider’s examination of what she gained and lost. Her memoir is wrapped up in her dreams as well as the dreams of countless others, writing from the dual vantage points of Beauty and the Beast. Robb cites, among other issues “isms” such as sexism, favoritism, idealism, masochism. How far should someone go for the sake of Art? When is the line crossed?

Robb tells us she was “born in 1992: the Year of the Woman.” Back then, she “loved the hyperfeminine trappings.” Today her quest is to be “feminine but strong,” as opposed to ballerinas so weak from starvation yet they “danced through their unbearable pain,” Virtuosos of how to “suffer in silence.” Of how to disconnect from one’s body. A “perverse relationship with pain” that stuns and horrifies those of us in awe of ballet’s beauty and elegance. Time and time again, though, Robb reminds us that pain for a ballerina is a “source of pride.” Is this beauty-in-the-eyes-of-the beholder? A ballet culture gone terribly wrong? Seeing the world through a “ballet lens” versus a more objective assessment? The answers not as clear-cut as you might think.

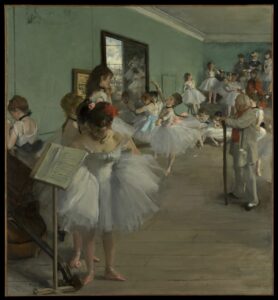

Balanchine’s approach isn’t a classical one like the dancers in the oldest ballet company in the world, the Paris Opera Ballet, the inspiration of Edgar Degas’ paintings Robb loves.

via The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Mr. B’s legacy is one of “aliveness, an energy that was new to ballet.” Great artists create something others haven’t. That doesn’t mean we have to think everything about Balanchine’s techniques and style are triumphant in achieving the effect of “ethereal fairies.” By making us take off our rose-colored glasses, the legend disturbs us too.

The audience for this artistic and cautionary tale well-exceeds ballet lovers. “To dance is a universal impulse,” even babies rhythmically move to music Robb points out. Broader than that are females obsessed with counting calories, have distorted body images, and battle anorexia and other eating disorders. (Affecting 30 million Americans, twenty million women according to this account.) Greater still are compulsive perfectionists. What are the benefits of pursuing perfectionism in one’s craft versus the damage of pursuing the impossible-to-reach goal of perfectionism in life?

Robb’s book reads like a perfect vision of a memoir: combining the intimate with stories of ballet student friends, interviews, and an extensive reading and recounting of other ballet memoirs, novels, research studies, blogs, magazines (dance and psychology); and watching numerous documentaries and movies. Way too many to cite, but you’ll find them listed at the back of the book in her “Reading and Viewing” suggestions and a twenty-page, single-spaced bibliography.

Full of contradictions, a few include:

- Ballet objectifies female bodies. Is this art, “sexual harassment,” or “mental torture”?

- We visualize ballet as the epitome of grace, whereas Mr. B sees his girls as “obedient animals.”

- Is ballet a stunning example of “stoicism” or “masochism”? Keep in mind every dancer worships Balanchine, wanting to push themselves way beyond their limits for him.

- Is this kind of behavior “resilience” or a “concession to a toxic culture”?

While reading ballet terms, one word you know but not in the context of ballet is “lengthen.” Code for “lose weight.” Another word we likely haven’t heard is “thinspo,” which stands for “thinspiration.” Ballet’s devotion may be inspirational but it comes waving a red flag.

This certainly isn’t the only ballet memoir published, but it certainly feels wide-ranging. A sample of ballet memoirs Robb dissects depicted in the images below include Misty Copeland’s Life in Motion: An Unlikely Ballerina; Margot Fonteyn: A Life by Meredith Daneman; Suzanne Farrell’s (with Toni Bentley) Holding on to the Air; Little Dancer Aged Fourteen: The True Story Behind Degas’ Masterpiece by Camille Laurens; Bunheads by Sophie Flack. They provide insight into what the culture means and demands, as well as the mental health benefits and deleterious focus on nothing else in a girl’s/woman’s life.

Not all ballerinas are in companies that relentlessly drum into a female’s head the “fat talk,” but Robb’s story seems to represent them. Which is why twenty-eight-year-old ballerina Michaella DePrince’s story and trajectory is so beautiful and uplifting. Escaping from the horrors of the Sierra Leone war, she danced with the Dutch National Ballet and the Dance Theatre of Harlem, now with the Boston Ballet (See: https://www.nytimes.com/2015/03/14/arts/international/for-michaela-deprince-a-dream-comes-true-at-the-dutch-national-ballet.html). Feel good watching her performing and looking athletic:

The pink pointe ballet shoes on the cover symbolize both the exquisite imagery and the pain of breaking in “custom-made shoes” that are “far from ready to wear.” Detailing the process is even painful to read. Robb’s characterizations are likened to a “crown of thorns,” a “bed of nails.”

Who knew there’s a world of “mother’s-of-dancers” online message boards? Robb disgusted by them calls them “cesspits of parental anxiety,” scornful of mothers who use their daughters to fulfill their unrealized dreams. These moms are different than the strict Tiger Moms who want their children to succeed; they’ve gone to extremes for their own selves.

One of Robb’s ballet student friends says, “Perhaps I can show the world that one defeat doesn’t mean the end.” Robb speaks about learning that the happiest former ballerinas found a way to “keep ballet in their lives.” The sense the reader gets, confirmed by Robb, is that writing is now her way.

We are the beneficiaries.

Lorraine