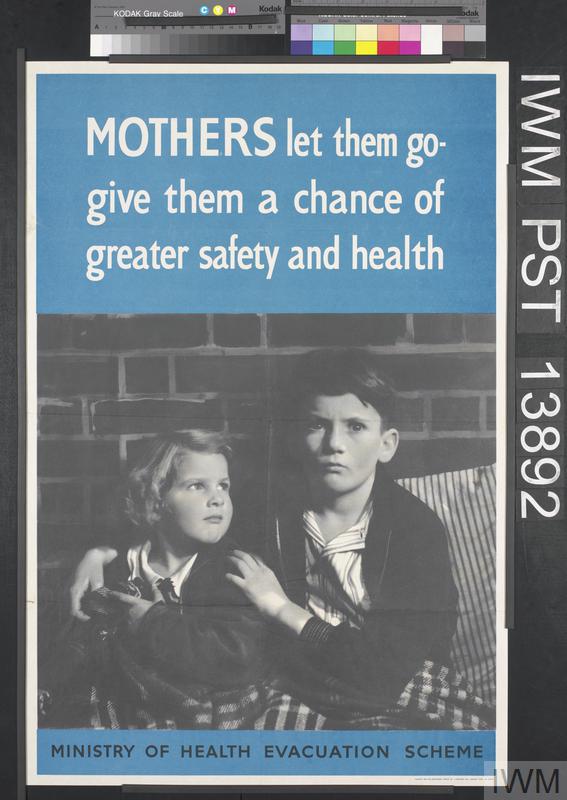

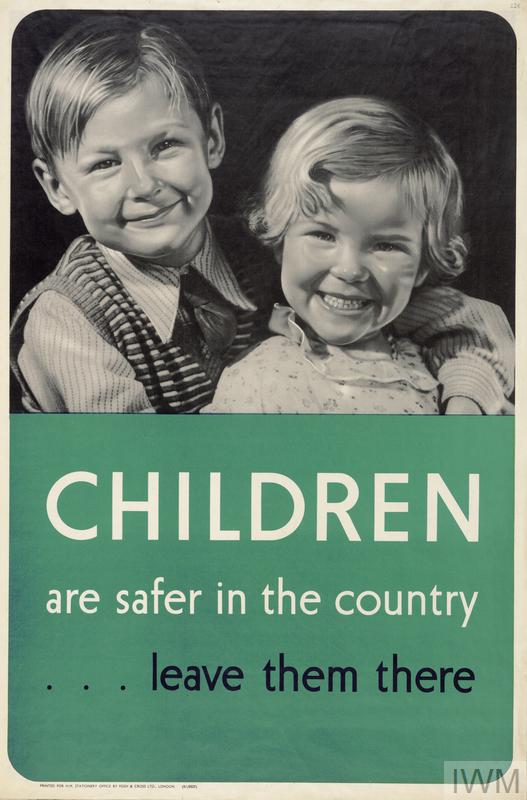

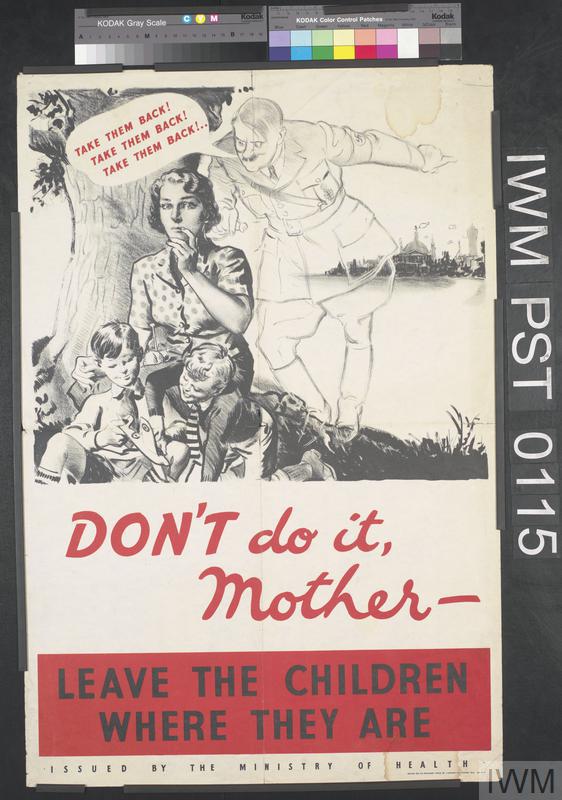

Think of the children (England, 1935-1952; New York City, 1935-1939): What’s worse? Separating children from their mothers during wartime or keeping them at home, hearing ear-crushing air raids and bombs, racing to shelters underground?

How will we really know how a mother feels when she’s made the excruciating decision to evacuate her child from war’s harm’s way when digitization erases first-hand accounts shared in war letters?

These two salient questions, the focus of this review, are raised in Julia Kelly’s newest, authentic-feeling historical novel, The Lost English Girl. A vivid example of why WWII fiction never tires, especially when new angles are delved into: Britain’s swift and sweeping evacuation of their children to the countryside, Operation Pied Piper. In the first four days alone, Kelly tells us 1.5 million British children were separated from their families beginning September 1939 when the Nazis invaded Poland.

Some children fared better than others. What happens to the lost English girl, Maggie, when her mother Viv decides to entrust her four-year-old daughter, likened to a “dark-haired Shirley Temple,” into the care of foster parents, strangers? How well does she fare? “I love you very much, Little Bear,” twenty-two-year-old Viv says crying while trying to smile as she hugged Maggie goodbye, with a mask hanging on her shoulder, “trying to memorize the warm feel of Maggie’s soft little body pressed against hers.”

via The National Library of Wales on Flickr

Heart-wrenching, the sadness Viv felt watching a nun board a train with the most important person in her world, to a place unlike anything where they’re from – Liverpool, a working-class port city. Whereas Maggie’s destination was Wootton Green, a centuries-old small village in the county of Warwickshire, “one of the prettiest towns in England.” In one moment – “just like that, they were gone” – one monumental decision changes lives forever.

by Nikki Mahadevan [CC BY-SA 2.0] via Wikimedia Commons

Viv’s tangled emotions are magnified over time in a series of heartsick chapters that inject her letters to Maggie’s foster mother, Mrs. Thompson, into the narrative. Tactfully, Viv’s first letter lets her know she wants to visit her daughter. With each polished and outwardly polite reply, the foster mom’s letters keep putting Viv’s visit off, shrewdly and intentionally rubbing it in that she and her engineer husband can provide for Maggie in ways Viv cannot. As Viv grows increasingly frantic, we feel the twisting of an emotional knife aimed at Viv’s vulnerabilities: torn between guilt, resentment, and jealousy that someone else is witnessing the joy of Maggie, her development and milestones, when she ought to be grateful for protecting her. The provocative letters show how complicated substitute mothering should be seen.

War letters were vital communications during WWII, thoughtfully integrated into the broader theme of war’s impact on children. Cinematic prose – scenes that feel like we’re watching an absorbing movie that sticks to historical timelines – ask us to think about the profound implications of WWII separations on today’s displaced children of war in terms of psychological trauma.

A recent survey by the Ukraine Children’s Action Project, launched by co-founder Dr. Irwin Redlener, examined the mental health impact of the Ukraine War on children. “Even if the war ends tomorrow, it will represent a very serious challenge for Ukraine and the rest of the world” with two million Ukrainian children psychologically and educationally devastated. Kelly reflects on the “impossible choice” parents faced to “send their children away without them so they could remain and fight” in Russia’s war in her Author’s Note.

Just as Maggie wins our hearts over, so does Kelly’s storytelling. No doubt the prolific historical fiction writer, with five novels published in the last five years (The Light Over London, 2019; The Whispers of War, 2020; The Last Garden in England, 2021; and The Last Dance of the Debutante, 2022, with The Lost English Girl the longest, weighing in at over 400 pages) – could have certainly dreamed up this twists-and-turns historical drama without a personal connection. But it seems to have contributed to the emotional authenticity of the prose since it was inspired by the author’s great aunt’s story who lived in Liverpool during WWII. “I wanted to know more.”

While we know about the London Blitz, we’re not as familiar with the Liverpool Blitz, the second most heavily bombed British city due to its strategic maritime location.

Kudos to Kelly for taking on this lesser known evacuation story, as many historical novels have concentrated, rightfully so, on the heroism of helping Jewish children escape from Nazi invaded European countries – Kindertransport. The last rescue operation was carried out when Kelly’s novel opens. Both rescues were endorsed by the British government, but the stakes were so much higher for those who risked their lives to save persecuted Jewish children. Less visible were the psychological dangers of evacuating British children of different faiths from their mothers. In fact, history didn’t fully recognize the psychological trauma until years later.

Music woven into the story appeals to the dreamers in all of us. Viv met her husband Joshua Levinson at a legendary chain of dance halls, the Locarno Ballroom. A saxophonist, he dreams of making it big in New York City’s thriving Jazz Age.

by Stephencdickson, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Viv and Joshua’s history is told in flashback-to-1935 chapters, when they were teenagers. Kelly knows how to get into a single woman’s heart when Viv lets herself go with a handsome man she barely knew. She and her sister were raised in a strictly controlled and deeply religious Irish Catholic home, with a cold-as-ice mother who ruled the roost and a mousy father who never stood up to her. The consequences of being the black sheep of the family kick the story off when Viv becomes pregnant with a Jewish man’s child. Anti-Semitism rears its ugly head within the family, and elsewhere.

Joshua’s family are seen as more tolerant and accepting. He does what was expected of an honorable man in those days, marrying her. But they never had a chance to find out if they could love each other and become a family when Viv’s Mom offers a nineteen-year-old dreamer an offer too good to refuse. You’ll see how that plays out in multiple storylines.

At the story’s root is attachment theory. A psychological concept associated with groundbreaking psychoanalysts – such as Erik Erikson’s stages of human development; Anna Freud’s (Sigmund Freud’s daughter) child development studies at Britain’s WWII “War Nurseries”; and John Bowlby, Father of Attachment Theory – are key to understanding the psychological risks and damage of breaking the mother-child bond.

This is also a tale about service to one’s country. Viv and Joshua choose different paths, but their choices provide invaluable comradery and friendship. Still, Maggie is the beating heart of the novel. Does she bond with her wealthy foster mother and father in their peaceful estate, indulged with pretty dresses, dolls, a neighbor’s pony she learns to ride? Or, does the bond between a mother-and-daughter prevail over things? How long can a child miss her mother without feeling abandoned? In this case, when too young to understand why she was sent away.

Is Maggie lost to Viv forever? Lost amidst the fog of war? Prepare to get lost in the reading.

Lorraine