The price of freedom linked to two historical eras and two real mysteries (New York City and San Francisco, 1922/23 and 1945): How does a WWII missing-in-action (MIA) story connect to the Jazz Age?

One era is associated with sacrifice, courage, and the fog of war; the other glitz and glamour. One defended democratic freedom; the other roared for individual freedoms. One somber; the other decadent. Yet both dangerous and plotted with secrets the reader comes to see are entangled.

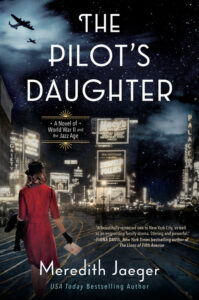

In The Pilot’s Daughter, Meredith Jaeger’s third historical novel (https://meredithjaegerauthor.com/the-dressmakers-dowry/, https://meredithjaegerauthor.com/features/boardwalk-summer/), she deftly engages by mixing two fictional historical periods and storylines. One set during WWII on the West and East Coasts, whereas the Jazz Age story could only be set in New York City. “Other cities tried to imitate New York, but none of them could capture the effect of jazz interpreted in light, a mile of streetlamps illuminating the car-choked streets around Broadway.”

Two women’s voices tell this entwined tale: Ellie Morgan, twenty-four-year-old daughter of an Army pilot who’s gone missing for six weeks in the vicinity of the coast of Italy and the Adriatic Sea when the novel opens, and her Aunt Iris, who’s been like a mother to her.

“Hope – a dangerous, slippery thing” characterizes Ellie’s pursuit of what happened to her dad, accompanied by her mother Clara’s sister. Clara is incapacitated – doped up and laid-out in bed. The two were never close, as she seems unable to say a kind word to her only child, thus her bond with Iris, who’s childless, and her dad.

The reason for stepping back to a glitzier timeframe arises when 1945 Ellie opens a package containing her father’s belongings. It arrived soon after the dreaded telegram military families live in fear of. Imagine being shocked again when she finds a cache of love letters stuffed in the pocket of his Army jacket, sent to him that he saved. They’re not from her mother or Ellie. They’re from another woman named Lillian who mentions a girl named Lucy, presumably her daughter. There’s an address: Greenwich Village, NYC. Despite the pain of what a grief-stricken daughter has just pieced together – that her beloved father had an affair and she may have a sister she didn’t know she had – in the crisis of the moment all she cares about is locating Lillian hoping she has information about her dad’s whereabouts.

[CC BY-NC 2.0]

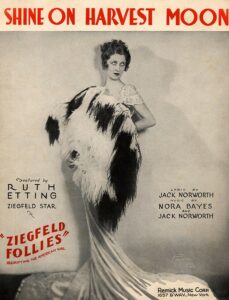

Lillian’s backstory dates to the Ziegfeld Follies. If you know NYC, then you know the street Lillian and Lucy live on – Bleecker. A markedly different street when the Prohibition ignited speakeasies, gangsters, and mobsters and the greatest show on Broadway: a singing and dancing sensation that lasted over twenty years.

A 1921 clipping from The Philadelphia Inquirer serves as the preface. It sets the theme of unresolved mysteries. This one involves the murder of a Follies chorus girl nicknamed the Broadway Butterfly. No spoilers fictionally except to say that Aunt Iris knows something about those days she’s kept secret, which means Ellie has no idea she’ll be dredging up some painful history. The murder of Dot King was never resolved.

A Broadway Butterfly

[Public domain] via Wikimedia Commons

Moreover, the MIA fiction dramatizes the real story of over 73,000 WWII veterans still unaccounted for. Ellie’s father flew a B-24 Liberator bomber. The last one built for the war, the Tulsamerican, is the subject of a PBS NOVA special, which the author refers us to in her enlightening notes, on searching for and bringing home the remains of 1st Lieutenant Eugene Ford whose plane went down more than seventy years ago.

How many years does a family search for a loved one? When do they give up? At this early stage of Ellie’s father’s disappearance, she isn’t willing to accept the Army’s conclusion, believing he could be injured somewhere or a prisoner of war. Will she find him? Alive? Or, gain some measure of closure?

Jaeger characterizes Ellie’s grief as “a pain that no one else understood. There are no rituals. No burials. No memorials and no closure.” A psychological term for this kind of enduring grief, also referred to in Jaeger’s notes, is “ambiguous loss.” Coined in the 1970s by Professor Pauline Boss, in the short video below she also describes this phenomenon as “frozen grief.” A concept that’s both a physical loss like Ellie’s MIA dad, or an emotional absence like her mother’s. A therapeutic diagnosis that’s wide-ranging, therefore relatable and poignant when there’s so much loss surrounding us today.

The reason this blog reviews a lot of historical fiction, beyond learning something new and inspiring, is that it’s often accompanied by compelling prose informed by terrific research. With all that’s at stake, Jaeger delivers old-fashioned, nostalgic prose using words that fit the times like “for heaven’s sake,” “swell,” and “hullabaloo,” offsetting the heaviness of the costs of fighting for freedoms.

Not all is swell either with how women were treated in the 1920s and 1940s. Ellie is a secretary for the San Francisco Chronicle, yet she wants to be a journalist, someone taken seriously. The way newspapers treated women was vastly different during wartime when “women around the country were taking on men’s jobs to aid the war effort and proving how capable they were.”

Aunt Iris brings us right back to jazzy times when women were treated as “tramps.” When she tells Ellie, “Don’t ever dim your shine,” this isn’t just foreshadowing advice but based on past experience. Aside from the necessities of war, men during both historical eras felt women “weren’t supposed to have opinions.”

Not all of them, though. Again, the author shows us both sides, this time through romantic storylines. One involves Ellie’s fiancé, Tom, an Army sergeant stationed at Fort Winfield Scott near the Golden Gate Bridge. They’ve only known each six months, and she’s lonely. So we see what she doesn’t want to: that his conventional, suffocating attitudes and values brought up by an old-school, high society Atlanta family who prioritize appearances clashes with a headstrong young lady after truths and with career aspirations. Will she wake up to how wrong he is for her? On the other hand, she reaches out to a “legman” (a reporter who stays out of the newspaper office to track down scoops) who encourages her and is empathetic. She hasn’t met Jack Miller but his charm shines through the phone, which deflects from two otherwise tense tales.

Do not assume Ellie is a bold young woman. When she and Iris leave San Francisco by train for New York City, she’s way outside her comfort zone but she pushes herself. In doing so, she sends us a pointed message of finding the courage to stand up for the things that really matter.

“Losing my own father as a teenager shaped who I am, just as it shapes Ellie,” writes Jaeger. Compassion and empathy for her female characters who’ve also lost so much shines through her inviting prose.

Wishing readers everywhere the best during this uncertain holiday season. One thing that is a certainty is that when you find the right book for the moon you’re in, reading brings joy, solace, and inspiration.

Lorraine