The staying power of a passion for the natural world and science through generations of fictional characters and common themes (Upstate New York & an island off of Maine and New Hampshire; 1860s – 2018): “There were some advantages of being a writer of histories,” wrote Willa Cather in The Professor’s House. Andrea Barrett chose that quote to frame her new collection of six short stories, Natural History: Stories. Demonstrating she too is a writer of histories. Intricate ones.

History from multiple perspectives. Barrett’s literary history includes recognition with MacArthur, Guggenheim and NEA Fellowships; finalist for the Pulitzer-Prize; and winning the National Book Award for Ship Fever, a short story collection published in 1996 that’s also being re-released along with this collection. Personally, she once wanted to be a scientist, so she’s channeled her passion for “scientific inquiry” and the natural world into her storytelling.

History also seen through generations of fictional characters and themes connected to each other in this new collection (Barrett acknowledges not all the stories are brand new, but they’ve been newly adapted), as well as to Barrett’s earlier short stories and novels (see: https://www.andrea-barrett.com/biography). A compelling, complex concept of endurance, weaving together a rich body of work in new and altered ways.

This review is based solely on this new collection. Coming to Barrett fresh, having not read anything else she’s written, means Natural History can be read as a standalone. For new readers, a marvelous revelation when you figure out the commonalities. The aha moments take time to realize, whereas familiar readers will surely pick up on and be looking for the artful connections to previous books much sooner.

In Natural History, history is seen through characters, relationships, attachment to a place, and thematically, connecting fictional family histories spanning the 20th and 21st centuries. History is also part of the stories. Barrett is deft at mixing real and imaginary. She also emphasizes the importance of documenting history in terms of how life was experienced at a particular time.

In the cleverly crafted first story, “Wonders of the Shore,” Barrett has imbued her primary female protagonist – Miss Henrietta Atkins born in 1852 – with a lifelong dedication to biology as a high school biology teacher. You’ll read of former students who never forgot her. We know what that feels like, remembering a favorite teacher who made a difference in our lives. In Henrietta’s case, it’s appreciating the wonders of the natural world.

Opening with wondrous prose on the wonderment of the sea, Barrett sets the eloquent tone and intricate theme of the past and present converging:

“The sea-shore, with its stretches of sandy beach and rocks, seems, at first, nothing but a barren waste, merely the natural barrier of the ocean. But to the observant eye these apparently desolate reaches are not only teeming with life, they are also replete with suggestions of the past. They are the pages of history full of fascination for one who has learned to read them.”

Inviting us to read with an “observant eye,” it’s still easy to miss the subtle slipping in of the name of Henrietta’s relative, Rose Marburg. For those who haven’t read “The Marburg Sisters,” a 1994 story referred to in the author’s note, when we meet up with Rose again in the last story bearing the name of the collection, it hits us how skillfully the generational threads are pulled together. To make sure we don’t miss that, like the author apparently did in her 2007 novel The Air We Breathe in which she includes a genealogical family tree to stress how characters are linked to Ship Fever, she’s done the same for this new collection. A two-page, multi-family genealogical tree comes at the end to surprise, confirm, and clarify.

In the opening story, Henrietta’s closest friend, Miss Daphne Bannister, has invited her to spend a few summer weeks on Appledore Island. For those who know New England places, the island isn’t familiar so we think it’s fictional. Googling you’ll learn its real, located on the Isles of Shoals Archipelago.

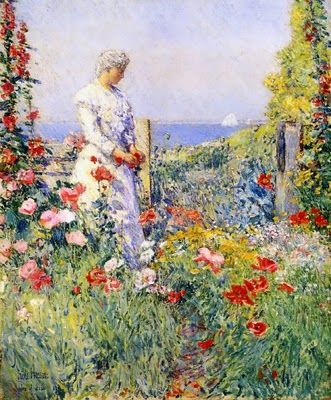

Daphne is also a scientist, a wildlife expert on insects, wildflowers, plants, birds. She writes technical guidebooks and other nonfiction, one the title of the story supposedly published in 1889. Googling it appears not to exist. Yet another book cited, An Island Garden published around the same time, is real! Barrett teases and challenges. Continuing with the cottage the two women are staying at. Owned by Celia Thaxter, who was a poet and lived in a cottage with a lovely garden on property alongside what was then the Appledore House Hotel. Other guests in the story, friends of Celia’s, were historical figures who frequented this island artistic haven, to include painters William Morris Hunt and Childe Hassam; and writers and poets National Hawthorne, Charles Dickens, Robert Browning. Turns out Hassam actually illustrated Celia’s garden book with the recognizable painting “Celia Thaxter in Her Garden.”

via Manchester City Library on Flickr [CC BY-SA 2.0]

The relationship between Henrietta and Daphne, both of whom chose singlehood, delicately raises the question as to whether their relationship was more than meets the eye since they’ve been vacationing together for many summers. The stronger impression, though, is of a professional, scientific relationship in which Daphne is seen as the overly ambitious one and Henrietta the kinder, warmer one. This judgment intensifies in the last, most recent story (2018) when Barrett makes the larger point (beyond women choosing marriage, motherhood, or singlehood) that women have made great scientific strides when they “find each other,” “stuck together,” and “made friends.”

Henrietta is featured in all the stories in one way or another. The setting changes to Upstate New York, where Henrietta lives. A common setting for the author who also lives in this region of the country.

Henrietta is selflessly devoted to others, whether it be to exemplifying how noble teaching as a profession is to nurturing curious young minds, or more broadly to the sacrifices women make as nurturers. Henrietta has been caring for her beloved sister Hester’s five children, all girls, over the years. Very involved with them, while Daphne is involved with herself. We greatly admire Henrietta; the jury has been out on Daphne early on when she treated Henrietta as second fiddle at Celia’s cottage. Female friendships are complicated and take work, seen in the closing story when Daphne appears at seventy-five and is still some part of Henrietta’s world.

In the second, poignant Regimental story Henrietta is ten, so the chronology isn’t straightforward. She’s working for a family that runs a pottery business. The husband has asked her to write letters to his two brothers, volunteers in the Union Army. Their regiment is stationed in northern Virginia, where many Civil War battles were fought. Again, unfamiliar history is woven in citing the use of observation balloons for reconnaissance. There actually was a Balloon Corps in the Civil War. But it’s the history of “hydro-aeroplanes,” a “dirigible engine,” in WWI and later the Hindenburg Disaster we know of. Interestingly, aviation appears in the fourth story “The Accident,” involving one of Henrietta’s nieces Caroline, another woman who chooses an unconventional career.

The other two stories, “Henrietta and her Moths” and “Open House,” deepen and enlarge interconnected themes on the natural world, science, and personal histories.

In writing about real history, Barrett shows the benefits and drawbacks of in-the-moment impressions when raw versus reflecting later within the larger context of history when memories over time can become “compressed and expanded.”

Warning about “stories tangled together,” these masterfully tangled stories will keep readers on their toes.

Lorraine

Fantastic review

Leaves you wanting to read more of her work. Thanks.