Painting a literary portrait of a 19th century female trailblazer on a larger canvas than the art she left behind (Boston and Brookline, Massachusetts, and world travels; 1861—1924): Do you ever feel you were “born at the wrong time”? Isabella Stewart Gardner did.

“Is there anything more exciting than being understood?” she’s imagined asking. Is there anything more exciting than reading a novel by an author who shows us how deeply she understands her subject?

Boston’s Emily Franklin, a “lifelong visitor” of the Isabella Garner Museum in Boston’s Fenway area, seems ideal to capture the evolving “selves” of a woman who believed we’re “always finding our next selves.” Franklin’s literary selves include poetry; over twenty novels for adults and young adults; memoirist; and editor of short story collections. Still, a high-flying act to singularly compose an historical novel about someone whose husband “wanted to make me happy” but “did not always understand what might make me so.”

The Lioness of Boston – even the lions have multiple meanings – is an outstanding read about a woman before her time. The prose is exquisite – elegant rising to poetic, evoking Isabella’s artful soul.

Most of the novel is set in Isabella’s grand, six-floor, townhouse-mansion on Beacon Street in Boston’s Back Bay neighborhood, once swamplands, where she lived when she married John Lowell Gardner – Jack – at twenty, moving there in 1861 during the Civil War. By the time the vision of a museum becomes a reality, Isabella’s collections outgrew their home. Located about fifteen minutes away, the museum sits on parkland designed by Frederick Law Olmsted, befitting Isabella’s love of walking through Boston’s Public Gardens, America’s first. Venturing out alone was scandalizing, one of many outrages that followed her through decades. Mostly structured chronologically, the novel lets you see her evolution.

Among the novel’s pleasures is tracing her early feminist thoughts and actions. Invigorated by more men than women who accepted her unorthodoxy as they were actually interested in what she thought, initially Harvard men of the arts and sciences. Drawn to progressive mindsets, proponents of aesthetics yearning to be “more than I was,” the novel reads like a Who’s Who of famous and lesser known painters, writers, suffragettes and activists of other social causes. The lioness was an outspoken free-thinker, romanticist, lover of beautiful things and landscapes. Above all, a fierce seeker of a purposeful life.

Franklin opens our eyes to a woman who left her mark on an aristocratic society, though she’s been more likely known more for the unsolved 1990 art museum crime of stealing thirteen paintings (a $10 million reward awaits) rather than for everything contained in her museum of memories: paintings, rare books, objects d’art, sculptures, antiques, and more, including its Italian architectural design because Venice stole her heart.

By King of Hearts [CC BY-SA 4.0] via Wikimedia Commons

Divided into four Books subtly titled with ISG’s different names characterizing her unfolding selves – “Belle,” “Mrs. Jack,” “Isabella,” “Isabella Stewart Gardner” – Isabella comes alive using three literary approaches: chapter narratives; intimate Intermezzos that reveal her innermost thoughts, feelings, intentions; and an epistolary format reflecting the abundant letters she exchanged.

The letters, interspersed, begin early on with her sole two yet dear female friends, Julia and Harriet. (Julia from her early Paris boarding school days; both she and Harriet Jack’s sisters). Expanding to the blooming relationships she cultivated with men, along with growing friendships with other nontraditional women. Isabella had contempt for “intolerance” in all forms, championing injustices towards women and men, such as gender inequality, the right to vote, gender identity, slavery, and anti-Semitism. For that alone, she should be remembered.

by John Singer Sargent

Photo by Peter E via Flickr [CC BY-NC-SA 2.0]

One of her closest male friends was the painter John Singer Sargent, who wrote in a fictionalized letter he needed “to remind you always to shine within, no matter who the onlookers might be.” His artistic style of “bringing light into the darkness” matches Isabella’s yearning “to matter. Or have what I do matter.” Someone who wants to “help us find the courage to be ourselves.”

Literary Henry James and the Jewish painter Bernard Berenson exchanged voluminous letters with Isabella. Fascinating Franklin made them her own when the Museum houses cases of the originals.

“Belle” is the self who says: “Parts of me longs, truly longs, to belong. And still another part wonders at a greater land.” For painfully too long she fought to be accepted into the exclusive, Puritan, elite upper-crust Boston male world – the “Boston Brahmins.” Having come from New York City’s upper-class, she wasn’t prepared for the severity of being judged as so out-of-place. The difference between a predominately homogenous New England community to a more culturally and ethnically diverse metropolis a factor in the prevailing conventions she confronted that made her feel a “sad magic to being a female.” A “gnawing emptiness.” Isabella fought gallantly, except for an exceptionally fragile period of grief and despair when she suffered three tragedies. Hers is a story of how “strength is from suffering.”

Travel saved Isabella’s spirit and soul repeatedly thanks to Jack, a Boston Brahmin who nonetheless opened the “wideness of the world” for her traveling the globe together for months at a time.

by Antonio Mancini

Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

The Who’s Who includes Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, who saw himself as an “awakener” and Isabella “trying to be awakened.” Also, artists and writers James McNeill Whistler, Mary Cassatt, Edith Wharton, George Sand (Amantine Lucile Aurore Dupin who dressed like a man since it was much easier to be one), Maud Ward Elliott; and activists Lucy Stone and Julia Ward Howe (Maud’s mother). The historical figures you’ll meet could easily make up an Appendix of Enlightenment and Insight. For instance, Dr. Rebecca Lee Crumpler was the first black woman in America to become a physician; Harvard’s first art professor Charles Eliot Norton, whose legacy lives on in the Norton Lectures; and painter Bernard Berenson who illuminates Jewish persecution in the 1800s.

What’s not to love about a woman who refused to “build a fortune or find meaning at the expense of others”? Who speaks about a “candied afternoon,” acutely aware of special, fleeting moments in her emotional roller-coaster life.

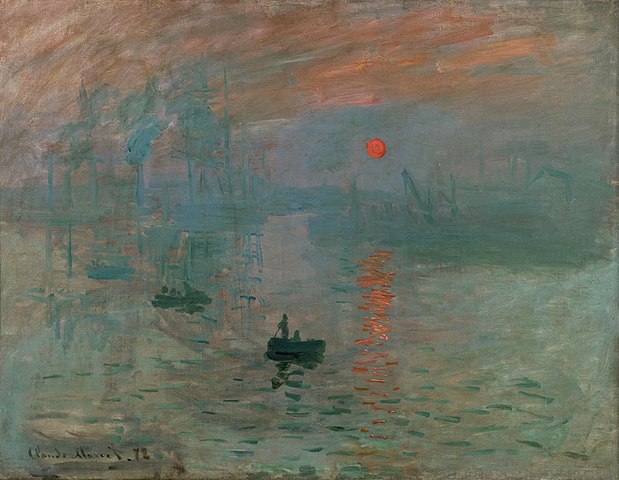

One of Isabella’s delightful awakenings happens with Jack when they traveled to Paris to the gallery of another female art pioneer: Berthe Moriset (see https://enchantedprose.com/pow-right-in-the-eye-thirty-years-behind-the-scenes-of-modern-french-painting/). The Berthe we’re treated to introduces Isabella to many struggling artists, such as Edouard Manet and his painting “Sunrise Over Water” with its “quality of realism infused with sadness” before the art movement became known as Impressionism.

Public domain via Wikmedia Commons

“Art makes you desirous. What more could we want?” says Berthe, whose “grace and sadness and art and purpose, all sheathed in the act of not being sure what she was doing, only that she wanted to keep doing it” describe Isabella too. She may not have possessed the equilibrium of Julia and Harriet, who between them had seven children, all boys, but showed her grace in other ways. Motherhood consumes a big chunk of Belle’s early days, leaving a lifelong effect on her.

The Lioness of Boston is every bit a triumph as Franklin’s eventually triumphant subject. I closed its 369 pages the day Boston’s Harold Kushner, Rabbi Laureate and mega-bestselling self-help author passed away. One of his books, “When All You’ve Ever Wanted Isn’t Enough: The Search for a Life that Matters,” sums up Isabella’s questing life.

A reviewer called Kushner’s first book “Why Bad Things Happen to Good People” a “spiritual survival manual.” For anyone needing inspiration for a path forward to live their lives with existential purpose, The Lioness of Boston offers ways for healing and setting us free.

Lorraine