How the sorrows of a white Afrikaner family reflect pre- and post-Apartheid (Pretoria, South Africa; 1986-2016): “Why is there not one normal person” in this novel? A question – adapted from the epigraph in which an odd woman ironically asks of film director Federico Fellini’s movies – you might ask of the characters in The Promise, the 2021 winner of the Booker Prize. Because Damon Galgut’s brilliantly conceived historical novel (his ninth; two earlier ones nominated for the prize) is hard-hitting and unusually written.

A different, yet related question frames the premise of the novel: “How did it become so complicated?” Galgut answers by tracking thirty years of a chaotic, conflicted white Afrikaner family, with its own share of odd (and prejudiced) characters, against the backdrop of a country’s turbulent history.

The most palpable and haunting injustice is racist based. A promise was asked by Rachel Swart on her deathbed at forty when the novel opens. Her demanding, insensitive, unfaithful husband Manie promised he’d keep it, but doesn’t since it involves a black woman – the long-time maid who helped raise all three of their children and care for dying Rachel.

Manie owns lands and a farm near Pretoria, South Africa (where Galgut is from), drives a Mercedes, and co-owns a reptile park (“always obsessed with the cold-hearted sort”), exemplifying white privilege. Land ownership is one of the legacies of Apartheid the democratic government has yet to rectify. Its significance in the Swart family’s story reflects that.

The title implies hope. Had the promise been kept it would have been a hopeful sign in a changing country. Unmet, it sets the hopelessness tone of a family that’s lost its way. Traced in four, long chapters named for Ma and Pa and two of their three children, revisited roughly every ten years: 1986 before the end of sanctioned racism, 1995 when Nelson Mandela became the first President, through 2004 and 2016 chapters.

The death of former white Afrikaner president FW de Klerk while I was reading the novel, a man who’d been for and then against apartheid policies (not as forcefully as the world hoped), intensifies the reality of the family’s story, echoing the intensity of the promise of democracy. “One of the most emotional and political transitions of our time,” remarked Princeton Lyman when US Ambassador to South Africa.

Described as a “spiritual pageant,” Mandela, wearing a “green Springbok jersey,” awards the Rugby World Cup to Francois Pienaar to a cheering, grateful crowd, showing a grateful nation in 1995 when Apartheid ended. Sports a meaningful way to break down tribal barriers. The reference is the most upbeat The Promise gets.

Instead of uplifting, what you’ll get is brutal honesty. Wasted potential. Lost opportunities. The importance of the church. Death. Racism and tribalism. Complexities and legacies seen through a complex family and a country’s complex history.

The novel defies expectations. The word tribe is frequently used. Expecting the novel to pit white against black, which it especially does in the unfulfilled promise, it also pits white against white, religiously and ethnically. The “pain and struggle” of one family invokes the country’s long history of pain and struggle.

The narrative style alone, unlike any other I’ve read, stands out. Shifting from 1st person to 3rd and the least common 2nd voice, alternating viewpoints aren’t separated by chapter nor punctuated; they shift within the same chapter’s sentences and paragraphs. The effect is altering Time, one of the themes. The prose sometimes feels dream-like/hallucinatory and stream-of-consciousness as narrators revert to the past, present, and future almost in one big breathe, amidst a country trying to forget its past and remake its future.

Contemptuous of the Swart family and extended relatives, the tone often sarcastic starting with the surname. Swart is an archaic word that means dark-skinned. The exception to this, in this reviewer’s opinion, is the way we view the youngest child, Amor, whom we meet at thirteen and already an outsider. The only person she’s affectionate with is Salome, the black maid; the only one who cares about fulfilling the promise.

Amor and Salome are the only two characters I liked. Amor because we empathize with her loneliness and trauma and she’s kind. Salome is the devoted one. Middle sister Astrid treats Amor condescendingly: “She was always thick with the underclasses.” Amor is also the only one who heard the promise asked and made, but no one believes her or chooses to disregard her.

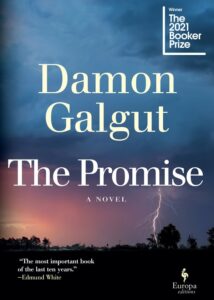

Like the title, we would have been clued into Amor’s importance had the US edition kept the original UK cover.

The picture of a young girl with penetrating, sad eyes would have focused our attention on her from the get-go. She’s also the only person in the immediate family that doesn’t get her own chapter. Lucky for her, actually.

Family “claws” dug deep into Amor’s soul, the reason she “never learns to live properly.” Astrid is the one who overlives. Anton, the “prodigal son,” the “golden boy,” struggles between underliving and overliving. He’s nineteen when the novel begins, conscripted into the army, a policy that ended when Apartheid did.

For a novel structured chronologically through three decades, pages, sentences, words, and thoughts blend past, present, and future. Each sibling chooses a path in reaction to the past and/or present. “Time has played on all our faces.” Playing with time doesn’t let us forget how it was and could have been. Anton wants the most; Amor believes “to move forward its best not to look back.” When forced to, she recalls, “Home used to mean only one Thing, not a blizzard of things at war.” Her overbearing aunt, Manie’s prejudiced sister, Tannie Marina, who appears on page one (her follower husband, Uncle Ockie also dislikeable) agrees: “We’re not going backwards now” on honoring the promise. Ironically, keeping the promise would signal moving forward.

Anton’s white girlfriend thinks “the problem with the country . . . is that some people just can’t get let go of the past.” The plight of the homeless, another character, shows “time passes differently for the homeless.” “For those shut out of the world.”

Multi-layered, the novel feels much longer than 269 pages. I don’t pretend to understand the country’s history of a “wretched struggle to survive” like Anton says about himself, but references googled give a sense of how much is packed in.

Two centuries ago, South Africa’s constitution guaranteed freedom of religion, so this is a diversely religious country. Rachel apparently left Judaism to worship in Manie’s church, the Dutch Reformed Church, second largest in this predominately Christian country. Converting back to her Jewish roots so she can be buried in the Jewish tradition is carried out but not without resentment and discrimination by Tannia: “Why couldn’t my brother marry into his own tribe?” Followed in the next sentence by, “I made a mistake, he said, and you pay for your own mistakes,” switching narrators.

Other than Jewish genealogists, how many of us know the history of Jewish migration to South Africa? The vast majority are Orthodox (unlike the US), including Rachel. Religious conflicts are seen as tribal. Rachel’s story is a great example of that.

The larger and best-known white tribal conflicts are between Afrikaners who speak with a Dutch accent as distinguished by English-speakers. Language differences are also rooted in complex historical legacies.

Arriving at a time when democracies are being seriously challenged, the theme of keeping promises is a valuable lesson. Even when the truth is hard to swallow.

Lorraine