Inside a specialized world and how it can help us (Cuba, eastern/western US cities, Israel, Rome, Haiti, Trinidad; 1950s to present-day).

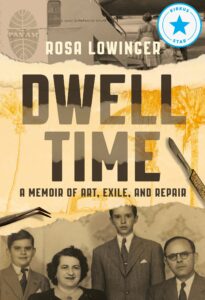

“Love is a phenomenal adhesive,” says Rosa Lowinger in an interview about her groundbreaking memoir, Dwell Time: A Memoir of Art, Exile, and Repair. The distinguished Conservator in the arts and architecture traces her personal and professional lives uniquely. Opening up to outsiders, as a first, her scientifically-based, highly specialized academic field, she then applies the materials, concepts, and philosophies of her discipline to her personal story, with important lessons for us.

Dwell time is a term that refers to allowing enough time for the chemical processes in conservation work to set. To bond. In turn, we’re asked what happens when not enough time and attention is given to our human bonds?

An impactful memoir that dazzles comparing what Lowinger learned over her forty-year career that also offers a special way to understand healthy and unhealthy relationships:

“There’s no magic here. It requires talented hands, but also belief and patience. That’s true of all repair, redemption, healing, restoration. It only works if you start with the notion that you have a chance of succeeding.”

Conservationists are careful not to jump to conclusions too quickly in determining the cause of damage and best method for fixing what’s broken. Similarly, we see how Lowinger’s palpably painful physical and emotional abusive upbringing is told with care, not condemnation. With an empathetic, tender eye, she examines the root cause of her mother’s uncontrollable rage beating her only child for hours, and her father’s anxieties, fears, “manipulations.” A man who’d “shrink under the weight of what could have been.”

The understanding the author displays in her challenging interdisciplinary field is also seen in her understanding of her parents’ and grandparents’ trauma as East European Jews fleeing 1920s Romania escaping sweeping antisemitism for tolerance, setting out for America but only making it as far as Havana, Cuba due to US legislative immigration quotas. Havana is Rosa Lowinger’s birthplace and where she lived until her parents were able to immigrate to Miami when Castro took over. One of the historical surprises is how welcomed Jews were in the pre-Castro days (20,000 Jews back then, today dwindled to around 1,000).

Lowinger’s escape from her toxic family environment is arresting, brilliantly compared to the toxicity of plastics. And yet, she’s also able to appreciate the good too. “There was also active kindness, humor, and generosity in my family,” she says. Over the years, she’s learned acceptance and forgiveness, but will never forget.

Conservation is a “transformative profession.” Lowinger’s early life was transformed by her future profession. By her scholarship, determination, creativity, independent-spirit, and a humanitarian’s passion to lift awareness, restore, and preserve art, history, culture, humanity around the world. Proof also comes from noteworthy achievements, building “one of the largest woman-owned art and architectural conservation firms” in the US and winning the century-old Rome Prize awarded by the American Academy of Rome in 2008.

Lowinger doesn’t dwell on the trauma inflicted on her. By page sixteen, she dives into her first prestigious conservation project for New York City’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, restoring a rare Numidian marble fireplace mantel from New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art collection from Cornelius Vanderbilt’s Manhattan mansion. Ambitious, she moves from one fascinating and different project to another while weaving the intimate into her story.

Lowinger does want us to know her non-professional diagnosis that her mother suffers from a personality disorder stemming from permanent psychic damage having spent ten formative years from ages four to fourteen abandoned by her own father to a Cuban orphanage. For all the damage she does to her lonely young daughter, she repeatedly tells her she did everything out of love.

“How do damaged items become whole again? How much destruction is necessary in a cycle of true repair?

Damage connects Lowinger’s personal and professional lives. Chapters are organized by the damage to the materials of conservation: marble, concrete, ceramic, plastic, bronze, bone, pigment, silver, terrazzo, wood, steel, mosaic, paint, glass. Disasters and graffiti complete the chapters, screaming for repair.

“Conservation is a mix of art, science, and hand skills, but it is fundamentally the art of understanding damage.”

Lowinger can also be seen through the lens of healer. “Conservation is a healing art.” For us, the eloquent and compassionate prose loaded with poignancy captivates, teaches, and helps us see ways to better our lives.

Inspired by Primo Levi’s masterpiece memoir, The Periodic Table, Lowinger has swapped Levi’s literary structure organized by chemicals with the materials of art and architectural conservation.

Lowinger connects with Primo Levi. His Holocaust survival story is the stuff of “martyrs and saints,” as noted in the video clip below. Levi was a chemist from Italy. Drawn to his extraordinary story and powerful writing, her memoir opens with his belief: “Understanding matter is necessary to understanding the universe and ourselves.”

Lowinger’s tale brings a wealth of historical details to the narrative: Cuba’s revolutionary forces; America’s foreign policies; Los Angeles and Haiti earthquakes; black history riots in the poor Watts neighborhood of southern Los Angeles, also the site of her largest outdoor project (see below); environmental degradation of ancient Greek and Roman ruins along Israel’s coast. The list goes on and on.

By Moe.217 [CC BY-SA 4.0]

via Wikimedia Commons

Marble, the first chapter, introduces us to the conservator as “an expert cleaner of marble” like her mother. Marble, a polished stone associated with “wealth and elegance,” is strikingly out-of-sync with the Cuban orphanage that punished her unruly mother by having to clean food off of marble tabletops that wasn’t easy. Now 91, her mother is still feisty but more loving. Still, the indelible mark she left on someone she claimed to love left her daughter feeling: “Never being enough or always being too much.”

Cuba looms large – emotionally, architecturally, aesthetically, politically. Once a vibrant place of Cubist, Surrealist, and Fauvist art styles, its architecture had remained intact for half a century. Fast forward thirty years when the author first returns to Cuba, it has become “dense with very damaged concrete buildings” due to erosion from the salty environment. “There was so much contradiction here. So much wreckage mixed with so much beauty” is a statement about Cuba’s decaying structures as well as her troubled marriage at this stage of her life.

The Bronze chapter, like everything else, means more than the heavy metal’s use in the art world. Technology turned this corrosive material into important commercial uses, “reverting” back to something less “reactive.” Then hitting us with: “Don’t we all wish to revert to states of being that are calmer? To be less reactive to our surroundings and circumstances?”

In asking what’s “needed to be lost before we could be found?” Lowinger asks us to reflect on our unprecedented times.

Lorraine