How personal and world history made the man – the life of Thomas Mann (1891 to 1950; Germany, Switzerland, US): I love the sound of Colm Tóibín’s prose. It makes this ambitious biographical novel about a major literary figure of the first half of the 20th century even more special.

Tóibín’s character study takes in the full measure of an extremely complex man considered one of the greatest German writers, and yet he was hardly known. Thomas Mann’s classical novels drew from his extremely complicated family relationships and hidden gay sexuality, so to understand the man you need to understand the autobiographical aspects of his life that inspired his works.

From the opening line, you’ll feel like settling into the novel’s 500 pages: “His mother waited upstairs while the servants took coats and scarves and hats from the guests.” The prose is dignified like Thomas Mann was.

In 2004, Tóibín, an English professor at Columbia University, wrote his first biographical novel about another literary master – Henry James, his “favorite novelist”. The Master is a fitting title for the writer considered one of the greatest novelists of all time. Tóibín could just as easily titled this novel the same. Naming it The Magician, which comes from a piece of Mann’s family life, implies an exceedingly more playful man than he was. Serious, somber, and deeply reflective, Tóibín’s clear and insightful prose not only illuminates the man, but how history made him into the man he became. History takes on new meaning through the lens of how it affected him.

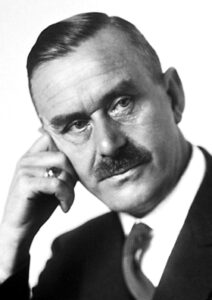

By Nobel Foundation [Public domain] via Wikimedia Commons

At an early age, Thomas Mann knew he wanted to be a writer. At 25, in 1901, his first novel Buddenbrooks was published, which, in 1929, he won the Nobel Prize for Literature mostly for. It, like others, was inspired by something in his life. Tóibín brilliantly tracks his life alongside the book Mann was writing at the time, so we see where the writer’s inspiration came from.

For example, Julia Mann, Thomas’ mother and the setting of Lübeck in northern Germany where he grew up, with its “atmosphere of mercantile confidence,” inspired Buddenbrooks. The Magic Mountain (1924) was inspired by his wife Katia’s treatment at a sanitorium in Switzerland; and Death in Venice (1912) was drawn from a trip Thomas and Katia took to Italy, where his “left-wing,” “internationalist” older brother Heinrich, also a writer, was living. Venetian waters and the gracefulness of a little boy mesmerized Thomas in this novel about a writer who had “no defenses against the vision of overpowering beauty.”

Just as Henry James hid his sexual preferences to protect his literary reputation, Mann did too. Three of his six children were openly gay and lesbian: Erika, Klaus, and Golo. So is the Irish author. Erika and Klaus’s relationship suggests incestuous feelings, as does Thomas’ for Klaus, and Katia for her twin brother, also named Klaus. One of the complexities explored, then, is the “sly persistence of the erotic.”

Thomas’ mother is an exotic character. Brazilian-born, Julia Mann was “dreamy,” artsy, bohemian, the complete opposite of his serious father. A Senator with a “century of civic excellence” and a prosperous grain merchant, Julia’s elegance did match his “sense of style.” After he died, Julia moved the family to southern Germany, to Munich, a livelier place that suited her better. Rather likeable, she “treated the most ordinary people as though they belonged to some exotic world.”

Katia was well-aware of where Thomas’ eyes roamed, yet let him be himself around her since he suppressed his desires. She, like Julia, had a “mystique of excellence” deserving of a full length book. Thomas eyed her in an opera box, as she reminded him of his mother’s good looks. Her father was a mathematician, a “fanatical Wagnerian” and friends with the composer Gustave Mahler; her parents cultivated a love of music, art, and literature, as did Thomas’. Their youngest child Michael became a composer and later a writer. (Three of their other children were writers too.)

Katia’s family was Jewish, the Manns’ were not. They didn’t practice their religion, so Katia’s Jewishness is presented in that light. Erika and Klaus were the most outspoken about Fascism, along with Heinrich who had a great distaste for “German manners” and desire for “dominance.” In a standout scene in Venice, Heinrich expresses these sentiments about Germany while Thomas argued (they didn’t get along at all) that Venice was “all surface ease . . . there is no depth, no tradition of serious thought, no homage to darkness.” He felt people “hate Germany because it means something,” that life must be viewed in “all its complexity.” Tóibín doesn’t shy away from all the complexities.

It’s Mann’s complete turnaround about Germany’s place in the world that Tóibín brilliantly shows us. In doing so, we also see what happens to a country that lost a war and was suffering, ripe for someone to come along telling grotesque lies destroying everything that came in the way.

Thomas is first seen as soulfully passionate about German exceptionalism. Eventually he can’t ignore Hitler’s evil, gradually speaking out when his family frees itself from Germany; when they immigrate to America he’s the most outspoken. Preferring the quietude of his study, Mann’s about-face as a political figure is spectacular.

Mann’s life also shows that you didn’t have to be Jewish to become an enemy of Nazi Germany:

“The very culture he had represented since the war – bourgeois, cosmopolitan, balanced, unpassionate – was the very one that they [Nazis] were most determined to destroy.”

The richness of Tóibín’s prose and imagination was inspired by access to Mann’s diaries from 1918 to 1921 and 1933 to 1950. The rest were destroyed, so the author fills in missing years using a long list of other resources he acknowledges – but all is penned through the magic of his prose.

When Mann received the Nobel Prize, 6 ½ million Germans voted for Hitler. Five years earlier, only a fringe element (3%) did. Mann went from “complacency to shock.” You’ll then first find the family in Lugano, Switzerland and southern France, until they fully appreciate that Thomas was “one of the most powerful Germans alive” and America is their safest option.

A vivid scene takes place at a 6,000 person event held on Harvard’s campus when Mann and Albert Einstein were invited speakers; both men arrived at Princeton University’s Institute of Advanced Study around the same time. Einstein, who by then had discovered his theory of relativity, remarked to Mann about how more roaring the crowd was for the writer over the scientist: “That is as it should be . . . If it were otherwise, there would be chaos.” Mann wasn’t sure what he meant, but it seems he was saying the writer organizes the world, the scientist confuses it.

In America, Mann also gets the attention of a woman who’s a force to be reckoned with: Agnes Meyer married to the owner of the Washington Post. She connects Mann to FDR; the two saw him as politically valuable for encouraging Americans to get into WWII. Despite disbelieving what they believed, that he was “a man of principle” and “clarity,” Mann picks up the mantel.

The message is clear: America needs more people of principle to protect our fragile democracy. Listen to the writer.

Lorraine