The ghostwriter who hooked millions of boys on reading (early 1900s–1975; Northern Ontario, Canada and Springfield, Massachusetts): How good a sleuth are you?

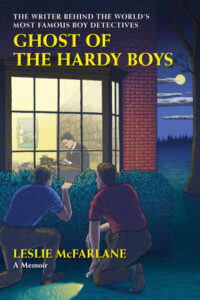

Did you detect the picture hanging on the wall, spying through the window of the nostalgic cover art of the Ghost of the Hardy Boys, is the cover of the first book in the original mystery series published in 1927, The Tower Treasure? In the spirit of anonymity, the identity of the good sleuth who clued me in shall remain a secret.

Talk about secrets! It took fifty years for “the writer behind the world’s most famous boy detectives” to reveal his identity – Leslie McFarlane aka Franklin W. Dixon – and for most of us another fifty years with the publication of this entertaining and enlightening memoir. First published in 1976, a year before the Canadian ghostwriter died, for most of us it’s likely these are brand new revelations about an indelible slice of Americana.

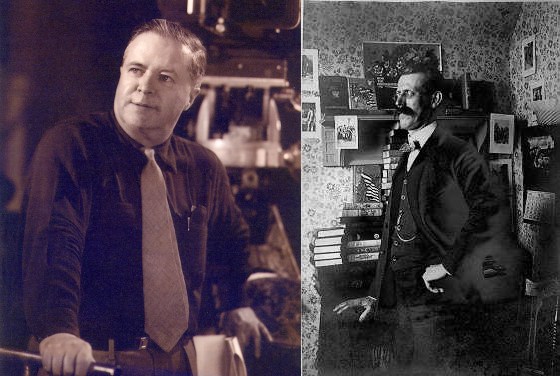

If you were a Nancy Drew reader, like I was, you too will find the memoir fascinating as both series (and The Bobbsey Twins, Tom Swift, Rover Boys, Dana Girls series) were the brainchild of the “sales genius” behind “one of the great merchandising ideas in the history of American publishing”: Edward Stratemeyer. Who? “A Henry Ford for fiction for boys and girls.” Founder of Stratemeyer’s Syndicate. Creator of 800 juvenile books.

Left: Courtesy of MacFarlane Estate via Godine

Right: Unknown author [Public domain] via Wikimedia Commons

Staying within Stratemeyer’s outlines – titles, characters, mystery – McFarlane “hammered out” the original 21 volumes of The Hardy Boys from 1927 to 1947, published by Grosset & Dunlap. His memoir is a treasure trove of early-19th century journalism, and one man’s control and transformation of the children’s book market.

Marilyn S. Greenwald, journalism professor at Ohio University and 2017 author of The Secret of the Hardy Boys: Leslie McFarlane and the Stratemeyer Syndicate, writes in her Introduction that The Hardy Boys were one of the “most enduring series in the history of young-adult literature.” (For a complete list see: https://hardyboys.us/hbos.htm.)

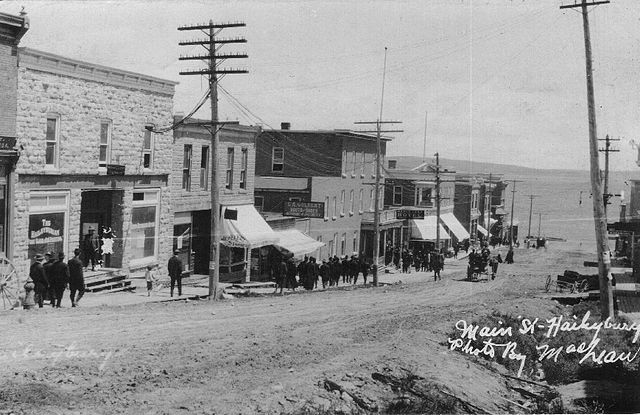

Via today’s sleuthing tool, you can learn that McFarlane’s fictional series in Bayport, Long Island, New York was “similar” to his hometown in Baileyville, northern Ontario. Ripe for two made-up boy sleuths – Joe and Frank Hardy, whose father Fenton was akin to Sherlock Holmes – yet adventures in some real places like Barmet Bay, Lakeshore Road, and cliffs. “How does one explain the subtle, magnetic attraction of one’s native land?”

By Unknown author [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Early on, you’ll read about the circumstances that led to McFarlane’s writing the first three Hardy Boys books. Published at the same time, the clever marketing “breeder” strategy meant the reader was apprised in book one that The House on the Cliff and The Secret of the Old Mill were awaiting. Circling back to the books later, he writes more about the books in the series. A technique he repeats when discussing the remote cabin in the Ontario woods where he wrote all the books after circling back home from America as a reporter for the Springfield Republican.

As of 1975, McFarlane tells us 11 million copies of his books were sold. But he never received name recognition for them, part of his benefactor’s strategy to be in command. Spinning a yarn about Ernest Hemingway, with whom he worked when the two were reporters for the Toronto Star, he warm-heartedly lets us know how he felt about anonymity. “No doubt a Nobel Prize winner feels pretty good when he learns he’s made it, but he can’t feel any more elated than a novice writer who sees his name in print.”

There’s no anger or resentment in McFarlene’s reflections. A “wordsmith” who admired great literature and “fine writing,” he doesn’t feel betrayed by Stratemeyer who paid him a pittance and became a millionaire. The chapter like “A Book is a Book is a Buck” shows he tells it like it was: these books weren’t the “Better Stuff” he aspired to but the reason he was able to eke out a living. “One should be thankful for whatever gift, no matter how small.”

Still wanting to incorporate some “embroidery” into his writing, “opting for Quality,” he created a character fans loved: Aunt Gertrude, his father’s sister. He also understood “you couldn’t go wrong by larding the action with a little funny stuff.” Years later his daughter says he “hated” the books, but in his telling he takes a pragmatic and generous tone.

“Honesty is everything,” the memoirist says, one of the life lessons he sought to instill. Another, a can-do spirit that nothing’s outside of a young person’s reach with enough “patience,” “luck,” and “ability.”

Nostalgia draws you to the memoir. To more “wholesome” times when our youth weren’t exposed to and victims of all the ills of modern society. As seen in his delightful writing and old-fashioned prose like “lads,” “rascals,” “scoundrels, “belly-buster,” “knee-slapper,” “tiddlywinks,” “buffooneries,” “gosh,” and “golly.”

McFarlane’s “comic itch” can be attributed to growing up on silent era comedians like Charlie Chaplain and W. C. Fields, vaudeville, and minstrel shows. That they included “blackface comedians from the American stage” like Amos and Andy brings us to bad nostalgia. Which opens up Pandora’s Box resonating the same racial and ethnic stereotyping complaints in children’s literature still seen today. Numerous websites discuss the racist, anti-Semitic, sexist, and derogatory language in the original series.

When Canadian journalist Bob Stall asks him how he felt about his books being “completely rewritten” (beginning in 1959), McFarlane knows they “aren’t the same books” (see here and here). He doesn’t say anything about the offensive prose. Rather, he discusses how “the old books were written for a literate generation,” pre-technology when kids had more time to entertain themselves, including reading versus the dumbing down of makeovers.

How to approach these sensitive issues in reviewing this charming memoir? Look for evidence of inflammatory language based on what’s written in the memoir. This is not a review, then, of the language of the actual Hardy Boys books.

Here’s what I found: McFarlane lived near mining camps and railway towns that attracted immigrants: “Finns, Ukrainians, Russians, Italians, Poles, and French-Canadians.” When he says immigrants need to learn English if they don’t want to be “an object of mirth,” he’s speaking to the importance of a key aspect to assimilation versus anti-immigrant sentiment viewing immigrants as objects of hatred and violence. When you come upon the word Swastika, your hairs stand up until you realize that’s actually the name of a real town in Canada. Why hasn’t the name been changed? When he says, “No popular magazine editor would go for a Good Guy who wasn’t a white man,” it’s a disturbing commentary but historically realistic. The most egregious depictions were his comments on dialogue excerpts a la Keystone Cops poking fun at the police. Not at all funny today, dangerous, though his intention was to show young people that it’s okay to question authority. These days, how we speak about law enforcement necessitates handling with care.

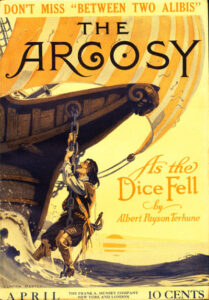

McFarlane’s lamentations on the loss of reams of defunct newspapers, weeklies, and magazines take center stage. He’s nostalgic for the days when you could pick up pulp fiction for a nickel or a dime.

“No ghost is irreplaceable,” he writes. You have to wonder if that’s true since Leslie McFarlane brought his small town boy’s sense of wonderment, adventure, humor, and attachment to a place from his early-20th century childhood into his books.

To Bob Stall, he says about his extensively remade mysteries: “Even a ghost has feelings.”

Lorraine