A literary artist paints big themes of America’s West and other frontiers through an FDR New Deal visual artist (fictional town in Wyoming, also Seattle, San Francisco, Florida; 1937): “We don’t know how any minute of history will play out,” says Val, the WPA New Deal muralist narrator-protagonist of Charles Frazier’s intriguingly told new historical novel.

Capturing the majesty of the American frontier landscape when America was limping through depressing economic times, The Trackers is living history America is still contending with. The prose is old-fashioned storytelling: muscular dialogue, jawboning, tall tales, legendary stories. It wraps art and adventure with economic, cultural, political, and moral themes into a mystery.

In 1997, judges of the National Book Award called Frazier’s debut mega-bestselling novel Cold Mountain “a vastly compelling narrative, and a useful mirror in which to witness ourselves and our perplexities.” The same can be said of The Trackers, Frazier’s fifth American history novel.

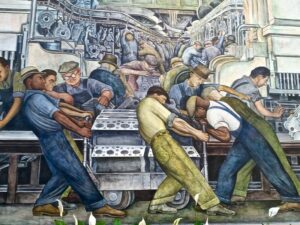

A fuller description might add how art critics described Val’s iconic heroes – painter and muralist Diego Rivera who left his mark on Thomas Hart Benton, depicting America’s grit and industrial engine – as: “socially and politically wide aesthetic vision, storytelling focus, and utilization of symbolism.”

by Diego Rivera

via Deb Nystrom [CC BY 2.0] on Flickr

via Garrett Ziegler [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0] on Flickr

The Trackers – a brilliant title since it has multiple meanings – begins and returns to Wyoming when it was still a wild frontier although historically the Wild West ended in the early 1900s. The standout prose isn’t a romanticized version of America’s Old West, even though twenty-seven-year-old artist Valentine Montgomery Welch III, Val, is a dreamer. A do-gooder who also needs money. The power of money is a big, conflicted theme: its role in America’s expansion, greediness, politics, relationships.

Val’s coming-of-age evolves from idealist to realist. The art plot embraces aspiration and optimism. Thanks to a former art professor, Hutch, Val landed a New Deal art commission to paint a mural in a small Wyoming town’s post office (one of 1,400 painted around the country). Val can’t put into words what he’ll end up painting, but he has a mental image of “the energy of America” that should reflect the region’s culture and hopefully lift the community up. The value of public art at a time when dreams were crashed is another thread.

Val’s progression spins-off the initial plot. The subplot consumes a chunk of the novel, turning Val into a detective.

Both storylines originate from Val’s benefactor: John Long, a wealthy cattle rancher who owns hundreds-of-acres and was recently married to younger wife Eve, with movie-star looks and mystique. Val’s plum deal comes with the perk of Long’s hosting him on his “enormous log-and-stone cabin” ranch property, complete with rustic cabins, horse barn, and that classy red convertible Packer on the cover resembling National Park WPA Poster Art.

Page one hints at whether Val’s stay will be as lucky as he feels with his first impression of the Long Shot ranch “hunkered against the world . . . As architecture, it made me wonder who it was afraid of or, conversely, who its anger was aimed at.” Prescient, because the more time Val spends with the couple, the more curious he gets about their relationship as tensions are exposed but not discussed. Eve is not the emotional kind, Long has his own agenda, and Val is in over his head.

Eve is a mystery. Once a cowgirl singer in a traveling band, she has a vagabond’s soul. Jaded, she believes most of life is a business transaction, except for dreaming. Val will come to question whether his dreams were worth the risks of doing business with Long.

Old Faro, Long’s longtime ranch hand cowboy comes across as scary, gun-toting. Don’t be fooled by his machismo as he’s a horse whisperer who keeps his sensitivities to himself.

Long has strong political ambitions, aiming for Governor, preferably US Senator. How Eve feels about that sets off alarm bells today on how far people will go for political power.

What Val has going for him is he’s cynical enough, and catches on reasonably quickly. Long, the guy with all the money, calls all the shots. Val, then, is willing to do his dirty work.

The mural will be painted fresco-style in the tradition of Mexico’s Rivera. The fictional Wyoming town Dawes might be a nod to former US Senator Henry L. Dawes and The Dawes Act of 1887, which impacted the Wind River Reservation. Long’s ranch “stretched west across sage hills to distant blue-black pine mountains in front of ghostly snow peaks flat as drawing paper against the sky, the Wind River Range.”

by Fredlyfish4 [CC BY-SA 4.0] via Wikimedia Commons

Historically and symbolically, Dawes represents power land grabs and injustice. The legislation deceived, billed as more land for American Indians but intended to get that land into the hands of White opportunists. Long, an art collector, owns some paintings by Charles M. Russell (1864-1926) known for “celebrating Indigenous cultures . . . while his art is considered historical, his spirit is timeless,” the C.M. Russell Museum states. Likewise, the novel‘s spirit feels timeless, and subtly makes a statement about America’s shameful treatment of Native Americans.

via WikiArt [Public Domain]

From the first sentence – “A Muddy Black-and-White Newspaper Photograph” – Frazier’s prose hooks us. Whether you view the novel from the standpoint of Art (each of its five Parts are named for the colors of Val’s palette: “Ten Thousand-Foot Blue”; “Charcoal and Umber”; “Rust and Chartreuse”; “Cinnabar and Azure”; “Indelible Black”), or as a detective story almost doesn’t matter. Honestly, we’re happy to go wherever Frazier wants to take us.

His prose sings – grandly, nostalgically, shadowy, sultry. It conveys Western ruggedness, breathtaking landscapes, the freedom of wide-open spaces and endless skies. Also looming is “whether the heaviness could overwhelm our desire to lift and fly to a better place.” Frazier isn’t just writing about a bygone era, but pointedly for today. Evidence includes: 1) Faro speaking of America’s future as he “how bad it’s gonna get . . . that’s how you’ll know the world has gone to hell”; 2) Hutch telling Val their world is a “different, harder world we were living in after the giddy” Roaring Twenties; 3) The Dust Bowl symbolizing the climate-change world we’re living in today: “drought conditions,” “front-page apocalyptic photographs,” “black blizzards,” “flooding rivers”; 4) Billy the Kid and other outlaw storytelling bringing out America’s increasingly violent culture; 5) and citing bad Supreme Court decisions.

Eve’s singing evokes a “mood more than a song.” Like Frazier’s prose that evokes moods contrasting the Depression against new feats of architecture Val found “oddly hopeful.” “Hope can sometimes be a sad thing, that or embarrassingly unhip, but I couldn’t help myself,” he says.

“Love and rejection and retaliation” are other moods coloring the prose. Whose love? Rejection? Retaliation?

Do you believe as Eve also does? “There’s not but one true trail through the world, and all the truth you can say of it is it’s there. Everything else is a guess.”

What about Val, who wants to have faith in public art to “elevate the country, maybe by only an inch, but every upward movement, however small accumulates”? One of the questions we guess at is whether today’s America would endorse a revitalized WPA art deal for the public good and struggling artists if it weren’t a money-making proposition?

Frazier wants us to reflect on what we could gain from the lessons of the past.

Lorraine