Why Andy Warhol, ultra-avant-garde pop culture artist, was a lightning force for vulnerable girls during a historically revolutionary era, and why it matters (NYC, 1966 to 2010): “Do you ever feel like no one is listening to you?” asks the aching voice of Mae, narrator of this hypnotic, edgy coming-of-age debut. Even the title announces Irish writer Nicole Flattery’s contradictory story of a young woman’s craving to remake her unloved self into something special.

The bulk of this fictionalized historical retrospective takes place inside the underground nerve center of sensationalism and extremism at Andy Warhol’s NYC’s art studio during the late 60s, known as The Factory.

Mae was a profoundly lost soul when at seventeen she landed a job inside Warhol’s feverish sanctum as an “invisible” typist transcribing audiotapes (alongside a second typist, Shelley) from sexually-charged, stream-of-consciousness conversations the radical artist had a penchant for recording, and they were aware of its publishing significance. In 1968, Grove Press released a: A Novel by the artist.

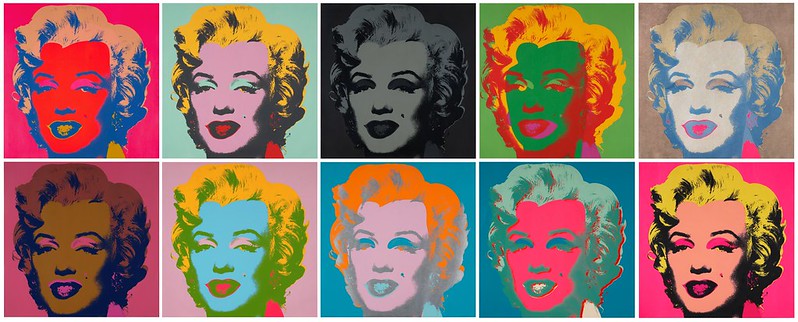

Bursting with complex and contrary emotions, unsettling frankness, insightfulness, and discomforting voyeurism, Flattery shows us that Warhol didn’t just push boundaries but had no limits, particularly when it came to what others held sacred, private instead of used for public consummation and commercialism. Warhol was openly gay, which gave his queer sensual work authenticity and a rawness that created an aura about him.

Nicknamed Drella, a contradictory cross between Dracula and Cinderella, raises one of the novel’s many provocative questions: To what extent was Warhol a groundbreaking artist or a brilliant marketer to make himself famous?

Questions pour out of us similar to the gush of emotions provoked by this fantastical novel. What is about our culture that’s so obsessed with celebrity no matter how far-out? What defines a great artist?

Andy Warhol wasn’t “just an influential; he created a new genre of contemporary art – pop art.” Originality, whether your taste or not, separates the greats.

The focus is really on Mae, who gets caught up in the cultish fanaticism for Warhol. Flattery shows us why. Mae calls him “he,” only twice cites Warhol’s name, giving the artist and her story a surreal quality.

Mae is thirty-five and sixty years old when she’s reflecting on those scintillating and “disorienting, shattering” Warhol years from 1966 to 1968. An extraordinarily lonesome and rebellious time in her life when she became energized feeling part of something special having never felt part of anything before.

The novel is not for the faint of heart. Its shock value is a wake-up call as to why vulnerable girls overwhelmed by a profound sense of aloneness/detachment/alienation, powerlessness, and ennui can be attracted to wildly unorthodox, charismatic leaders.

By Daderot [Public domain]

via Wikimedia Commons

Mae, from a broken family, justified her behaviors when “an entire city was tuned into a different frequency: young, wild, open to experimentation.” Flattery’s gutsy prose is a marvel of seduction. Seductive prose mimicking seductive Warhol. “What sort of pathologies did I possess that allowed” that? Mae asks.

Older Mae examines those “self-mythologizing” years when “we hurtled through two decades like falling from a high-window,” echoing how the reader feels hurtling through this novel and wondering why it was so gripping when there’s plenty to disturb? One way to think about the reading experience is to compare it to how torn you feel driving by a bad car accident, hearing the sirens, knowing you should not turn to stare because it’ll be disturbing and voyeuristic, and yet you do.

The sixties counterculturists were bold, principled, and influential activists who stood up to America’s denial of civil rights, gay rights, feminist rights. America is conflicted like Mae split between fighting for those freedoms, while others are working to deny them.

Warhol has an entire museum dedicated to evolving views and scholarship on his multi-talents – iconic psychedelic-colored silkscreen printmaking of the famous and the ordinary; painting; documentary filmmaking; and writing.

Mae (and Shelley) represent Warhol’s book world, and there’s a haunting scene when the two sit in a movie theater for three+ hours glued to his jarring film The Chelsea Girls.

Two strange, intense love/hate female friendships contribute to the contrariness of emotions. One, Mae’s only friend in high school, Maud, who became toxic for her, and Shelley, a runaway like Mae. She gets under Mae’s, and our, skin. What’s she hiding? She won’t tell Mae where she’s from, who her parents are, what brought her to the city, whereas Mae confides in her. She keeps telling Mae she’s her only friend, but you’ll wonder about that observing their competitive natures and the drama that ensues.

Despite not being acknowledged for their typists’ role in putting together Warhol’s novel, Mae doesn’t care for a longtime. The typewriter became her best friend not just for eight hours a day but to the exclusion of almost everything else back then. She found purpose, belonging even though sometimes she was “shocked by what I saw.” But she rationalized Warhol’s art as “exhibitionist” not “exploitative.” What will you think?

Why were Mae (and Shelley) able to listen so intently to tapes filled with profanity, coarseness, sexual eroticism when others couldn’t bear to? They’re fictionalized characters, inspired by the true story of typists who refused and others who didn’t. Voices heard on the tapes and in the studio are also drawn from some real people: Ondine, the dominant voice on the audiotapes was an actor called The Pope. Brigid, referred to as The Duchess, was artist Brigid Berlin. Edie, model and actress, was Edie Sedgwick.

By Laura Loveday [CC BY-NC-SA 2.0] via Flickr

Opening in 2010 with an insightful tale of a rare occasion when Mae’s mother is reading a book to her young daughter about a farm with animals, leading us to believe at first it’s a children’s book. Soon after you’ll figure out its Animal Farm by George Orwell, the experimental classic when Mae singles out the sheep that “took on existential qualities.” Is Flattery suggesting Mae and Warhol offer different viewpoints on the meaning or meaninglessness of life?

Mae’s family shows us how the breakdown of a nuclear family can dangerously affect a child’s persona and emotions. She can’t remember when her alcoholic mother gave her any “affection.” Worn down by life, a waitress paid low wages, eking by in a city that can make or break you. What’s she’s taught Mae is how hard, unfair, and undervalued life can be. No father in this picture. A boyfriend, Mikey, who moved in when Mae was eight. He comes and goes, while we keep asking why he returns? Their apartment is dismal, “characterless,” and her mother destroyed him he says like Mae does. Mae warms to him since he’s the only one paying any attention to her. We like him more than any of the other characters for that.

The bigger question is how likeable is the narrator? Like everything else, we’re betwixt-and-between about her. She cries out to us, but we don’t like what she does to herself. How reliable is she when she tells us she “strived for pleasantness in all things” yet repeatedly does unpleasant things?

Mae recognizes how her “sensational impulses” disappeared when she “stepped out into the real world.” Is that why Nothing Special lures us into her hallucinatory world? Hers is “quiet aggression” whereas ours is much louder.

Lorraine