Self-discovery immersed in the Dutch Golden Age (cities in The Netherlands; 1976 to present-day): “In every age, art is an experiment for every artist, just as, in every age, life is an experiment for every person,” wrote Benjamin Moser years ago in an article, Can Writers Still ‘Make it New’? Soon after, he wrote about writing as a “calling,” as “an inner purpose,” and “a means of understanding, and thus of elevating, our everyday lives.”

Those essays were written during Moser’s quest to learn “something new” about the great Dutch artists and their 17th century masterwork paintings as his way to understand and connect with the new country he moved to when he was twenty-five, The Netherlands. The Upside-Down World: Meeting with the Dutch Masters took nearly twenty-five more years to accomplish.

Can you imagine spending nearly half your life “consumed” by one thing? Granted a huge undertaking given how prolific the era was, and how difficult to unearth something new for most of the artists he applies a microscopic art critic’s lens to, most unknown to many of us. Repeatedly he chants, “Almost nothing was known.” The challenge for others, Rembrandt the most famous, was to discover something new that meshed with Moser’s mission to find “something higher” for mastering “something about life” – and himself.

From an art appreciation point-of-view, you will learn why Rembrandt was “great in every field,” even if many of his paintings are too dark and gruesome for your taste. The real intrigue, though, is understanding the man behind the book who devoted so much passion, dogged pursuit, research, and speculation immersing us in Moser’s study of the Dutch masters.

The writer sparks interest since the two books he’s written garnered the kind of recognition for excellence he strives for. Why This World: A Biography of Clarice Lispector was named finalist for the National Critics Award, Notable Book by the New York Times, and won Brazil’s Cultural Diplomacy State Prize for his biography of their Ukrainian-born novelist. Sontag: Her Life and Work earned him a Pulitzer-Prize.

As a reviewer of memoirs, I can offer opinions. Art historians can address the rest.

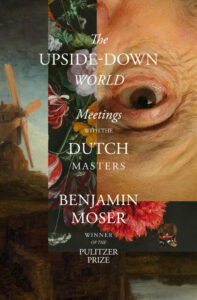

Handsomely designed with high-quality glossy paper and over 300 illustrations, Moser’s third book looks and feels like an art book. So why is it billed as “a revealing self-portrait”?

Because the memoir is something new. Seeming to say you don’t need to know my intimate details to know me. Know what matters to me, instead. Thus, casting an atmosphere of mystique like some of the artists known for their atmosphere, moods, perspectives.

Moser admires artists whose work is subtle. So is he. Attracted to the elegance of subtlety, he’s drawn to art that “evoked emotions that were more intense because they are indirect.” Is Moser explaining his memoirist approach demonstrates his intensity of purpose by being indirect? (Direct exceptions found in the Introduction and Afterword.)

“When you see Vermeer’s work together,” you “wonder what they are really saying,” echoes how we feel assessing what the author’s art critiques and commentary are really saying about himself.

The prose is both elegiac and down-to-earth. Valuing authenticity, not following another artist’s style, render Rembrandt’s followers as not rising to greatness. Great art doesn’t have to be loved, but it does have to create something unique.

Artists in this group include Pieter Saenredam’s architectural perspectives. “Was he aware, at the time, of the enormity of the task?” Moser asks. Is this also a statement about his young self when he began this enormous endeavor?

That the Houston born American connects with artists who “saw beauty in old things,” felt a “closeness” to these Old World artists tells you something about his sense of belongingness in a world that valued craftsmanship. A stiller world, one that brought him peacefulness.

“Puzzled” by the meaning of an artist’s painting seems to imply puzzlement with today’s upside-down world. This is also an art term Dutch artists used for describing art that turned the bourgeoisie world on its head.

Discussing “realism” versus “idealism,” Moser points out that although one of the genres the Dutch are famous for — still-life paintings — may not have been as realistic as they appear since life in the 1600s was harsh for the majority of Dutch people. Strikingly, many artists featured, and their families, died young. Forty, “old.”

We shouldn’t be surprised artists want to lift us up. Vermeer a prime example of brilliant light. Hendrick Avercamp for his spirited ice skating scenes.

Left: Vermeer [CC BY 3.0] via Wikimedia Commons; Right: Hendrick Avercamp [Public domain] via Wikimedia Commons

Moser too seeks lightness, “happiness” not loss. “Artists know their failures as well as anyone, which is why I don’t like to dwell upon this painful thought.”

The prose is the work of a wordsmith who has a “fear of ignorance.” You’ll learn new words. The one that pleases especially is sprezzatura, defined in the art world as a work that gives the impression of ease but took considerable effort – like this unusual memoir told through art.

You will come away with some historical details you won’t forget. For instance, 165,000 “starving” Dutch people after the Holocaust waited in long lines to see a Rembrandt exhibition. Mosher’s heartening explanation is that art is a “symbol of dignity of a free people.”

It’s refreshing that even though a “jewel-like” Vermeer painting may be “so perfect,” others “shocked.” Moser reactions are telling as those failed paintings brought him “closer” to the artist as “a man struggling” – like he apparently has.

Moser wrote the Vermeer chapter in the third-person voice – “the man who writes this sentence is forty-five years old” – when he could look back and feel “proud” of his work. The struggles he went through, he says, are no longer as important to him as when he began his journey. Failure isn’t “the end,” rather the “beginning.”

Moser has revealed himself as a man of seriousness, scholarship, dedication to writing as a noble profession creating his own “aura” of the grace he attaches to Dutch paintings.

The concept of grace plays out, then, artistically and personally. A painting’s “charisma” defined as “that indescribable quality of grace.” It’s one of many observations and speculations that make you stop reading to think.

Memorable painters include: Paulus Potter for the animals he painted that “elevated” their status – serene cows roaming, animals in the barn, majestic dogs. Jan Steen for his moods, “warning against vanity and vice.” Meindert Hobbema for the “balletic sway of the trees.” Jacob Van Ruisdael for his landscapes Moser explains differently than our Nature imagery. Its “land-shaped” reflecting how Dutch land had to be shaped by man due to its flatness and waterways. Moser feels “close to this invisible man,” to his “introspection” and “meditation,” aspects that fit his thoughtful commentary.

Top Left: Henk Monster [CC BY 3.0] via Wikimedia Commons; Top Right: Jan Steen [CC BY 3.0] via Wikimedia Commons; Bottom Left: Meindert Hobbema by Gandalf’s Gallery [CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 DEED] via Flickr; Bottom Right: Jacob van Ruisdael [Public domain] via Wikimedia Commons

Moser still lives in the same 17th century Dutch house in Utrecht when he set off on his coming-of-age journey. The same house Vermeer lived in! He loves – and we appreciate how much it means to him – to look out the same windows seeing what the great artist saw. Sharing what matters to him.

Lorraine