How the past stays with us (Vienna, Austria mid-to-late 1930s; Cork, Ireland 1980): “Art is flashes,” writes Billy O’ Callaghan, imagining what sports commentators might have said watching “maybe one of the greatest there’s ever been.” When “people came to see magic, and to have their breath taken away” by an Austrian superstar football player (America’s soccer). It’s impossible to separate O’Callaghan’s prose that takes our breath away from the legendary man who flew through the air “light as a breeze” – “The Paper Man.”

So why, O’Callaghan implies, don’t we know Matthias Sindelar (affectionately, Mutzl) the way we know of Brazil’s soccer legend Pelé? And, how come Ireland’s O’Callaghan isn’t as well-known to us as he should be, crafting such sadly beautiful prose? In 2022, I concluded his Life Sentences was an “awesome piece of literary craft.” The Paper Man is that too; this time expanding beyond Irish generational memories to Austria’s WWII history and a fictionalized love affair for the ages. Opening a month after the Nazis annexed Austria on a specific date April 3, 1938 – the Anschluss, which stood for Hitler’s grandiose unification plans. It was also the last time The Paper Man and his Austria Vienna team played for their country.

In O’Callaghan’s 2019 novel, My Coney Island Baby, he writes of dreamers and those “born to practicality.” In this dual timeframe story, 1930s Vienna is both the stuff of dreamers and then, catastrophically, collapses into the sheer practicality of survival.

First we’re treated to a man “so much more alive than anyone else,” who let others dream in those “genius at work” moments, ignoring the Fascist forces engulfing them. Early 30’s Vienna is likened to Paris in the 1920s when dreamers, intellectuals, and artists pulsated in a café society before Hitler destroyed dreams and lives. Dreaming and survival linked in the poignant Vienna storyline when thirty-something Sindelar falls soulfully in love with nineteen-year-old Rebekah, Jewish, a “girlishly pretty” café waitress. Yes, true love can happen “at first sight,” the name of the chapter. Until the Holocaust grotesquely twisted that love into survival mode.

The 1980 chapters are set in Cork, where O’Callaghan grew up and lives. A place “born of practicality,” especially seen through the fictional protagonist Jack Shine – Rebekah’s son. Compelled to separate from the love of her life, O’Callaghan lets us imagine how much more of a blow it must have been when his mother discovers she was pregnant. Had it not been for Sindelar’s connections, a fearful, circuitous route out of Austria, she probably would not have made it. Not to her parents’ village in Kaumberg but someplace safer, to her Uncle Joe and his wife Ruth’s Cork home. They accepted and loved her like their own, into their home in a small Jewish neighborhood of historical significance.

Jewtown originated in the late 1800s when Lithuanian Jews fled here escaping Russian persecution. O’Callaghan wants us to remember this mostly vanished community of “Hibernian Buildings,” that’s “tucked in behind the city’s docks.” When he says it was a place that “feels like the edge of the world . . . with no place left to run,” he wants us to remember Jews have a long history of persecution.

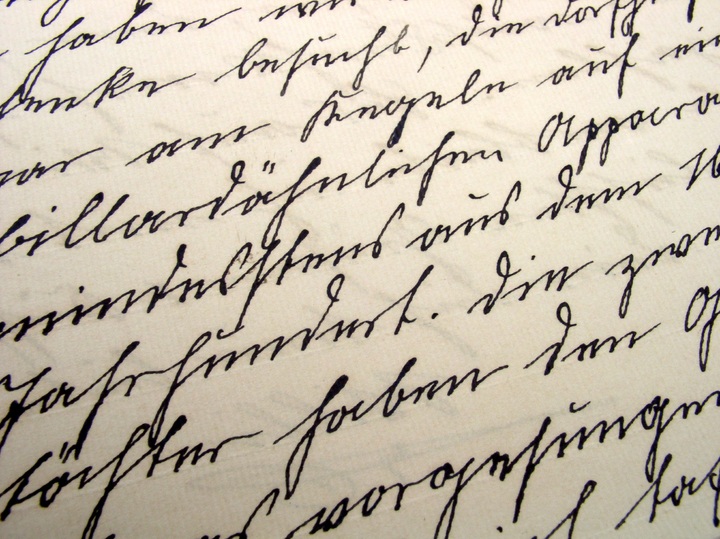

The Paper Man is a novel about remembering. Rebekah died when Jack was eleven; he’s forty-one in 1980. Though the “shadow of loss never completely fades,” the family that took in his pregnant mother became his parents, their two children his siblings, when Rebekah died some thirty years ago. Nurturing a “particularly precious sense of love and belonging,” the edginess of a gritty place softens. His biological dad may have been a man “who lived enough to fill a dozen lives” but Jack never got to glimpse even one. Had he not stumbled on a box of intimate love letters sent to his mother from a mystery man, he still wouldn’t. No one asked, no one knows. The discovery ignites an “intangible intensity” of needing to know. To remember. Turning The Paper Man into an immersive historical and fictionalized, unresolved mystery.

At thirty-five, Sindelar’s “firework” of a life was snuffed out, suspiciously and “terribly difficult to accept,” when he was found dead in his apartment. The cause of death declared carbon monoxide poisoning seeping into faulty ventilation. Some speculated if the cause was suicide, but that doesn’t seem to fit the man courageous enough to speak out against Hitler. Feeling on top of the world and Catholic, Sindelar played on a national team with Jewish players the Nazis contemptuously called Judenklub. Having never read a WWII story involving sports, Jew Club is a new word in the canon of anti-Semitism.

Since the letters were written in Old German, his father-in-law translated them for him, revealed a little at a time. He’s dear to Jack, where we see the same understanding, love, and support of his wife. (He’s blessed with a little girl too.) The letters stir both men deeply as it becomes clear Rebekah was once happy, not the suffering person remembered most dying from a disease associated with poverty. A few photographs were also found of the man who gave his team the glorious name Wunderteam.

Sindelar’s 1938 soccer performance was “an exercise in grand humiliation.” Could the Nazis have murdered him? Assumptions aren’t good enough for Jack, whose contented life has now come apart. And so the novel also becomes a tenacious, searching tale.

Sindelar possessed an “elegance of pose” likened to “watching a great dancer, that same godly elegance of power, grace, and musicality.” Captured by a writer of elegant, powerful prose that has a musical and poetic rhythm, crafting words that echo his forgotten hero: “Every touch, pass and dribble becomes a small glory in and of itself, an exhibition in the purest sense.” Words that are an exhibition on literary prose.

Prose that swells like the rising tides of the author’s homeland in close proximity to the sea and the dockyards – a “swelling boom.” O’Callaghan’s long, sweeping sentences, some a full-page paragraph, come in swells, creating an intensity matching the depth of emotions unearthed.

For all the complexities of delving into truths that are hard to put together when you’re “dealing with fragments,” and survivors who may not be alive anymore or their memories foggy and full of anxieties, the chapters hit on simple titles that capture their essence and trajectory. “Anschluss,” “Jewtown,” “At First Sight,” and “The Letters” are followed by “Falling,” “The Marina,” “Separating,” “Revelation,” “Arriving,” “Expecting,” “Searching,” “Dying,” and “An Ending” – which never really ends. Cork “a place of long memory,” and O’Callaghan a passionate writer who has pieced together fictionalized history that feels as real and alive as past memories can be.

Cork is where “men and women roll up their sleeves to work and who keep their horizons close and their ambitions small.” By giving Jack the backbreaking work of a “docker” (or longshoreman, stevedore) toiling in drenching rain and frigid, windy conditions, O’Callaghan also wants us to remember those vanishing workers once so vital to Ireland’s shipping industry.

The layered depth of emotions, humanity, and tenderness Jack brings to dark and troubled times is a reminder that “everyone carries their problems with them.” Yet Jack is wise. Our literary hero since he also recognizes that “what he has in his life is more than he ever wants to risk.”

Lorraine