Self-discovery straddling between two different American cultures (Puerto Rico and Western Massachusetts, 1958 – 1990): There’s many things the perceptive voice of the narrator, Andrea Rodriguez, doesn’t know (as well as us), distinguishing The Things We Didn’t Know from other migration stories.

Most significantly is that this coming-of-age displacement story originates from a territory of the US, Puerto Rico, not a foreign country. When we meet Andrea she’s spent four, young years in New England’s rugged Western Massachusetts, yet she and her younger brother Pablo didn’t know they were US citizens.

Most likely, we didn’t know their arrival during the fifties represented a “wave of Puerto Ricans” who came to the US mainland, which felt like a foreign land and culture, numbering around 700,000 by 1955, 1 million by 1960.

What also distinguishes this historical novel, perhaps not uniquely, is it’s told over thirty consecutive years. From the time Andrea was seven in 1958 to thirty-nine in 1990. Thus, a hard knocks story of hardships, acculturation, bilingualism, and hard-fought self-advocacy that reaches us someplace deep.

This is also a story of how a mother’s abandonment at a critically vulnerable time – when Andrea and Pablo were lost between two different worlds, languages, values, traditions, when they only knew basic, informal Spanish and hadn’t learned English yet – is seen as the catalyst of the family’s breakdown. Raquel’s spiraling relationship with her children from the beginning is foretelling, refusing to even try to adjust and learn English so she could help her children navigate two worlds. Andrea is most affected since she’s expected to assume all her mother’s responsibilities, while the impact on Pablo evolves differently. There’s a line in the novel that captures Andrea’s longing for a mother, commenting on her school classmate and neighborhood friend, Sally, whose parents “spoiled her with toys … But the best thing she had was her mother.”

There’s no shortage of books published over the past few years on how hard motherhood can be, and making the decision not to become a mother. Raquel angers us not because she’s stubborn and self-centered. Emotionally detached, abusive, achingly neglectful, she isn’t nurturing. The kind of person who should never have had children. What psychologists call Toxic Mother Syndrome.

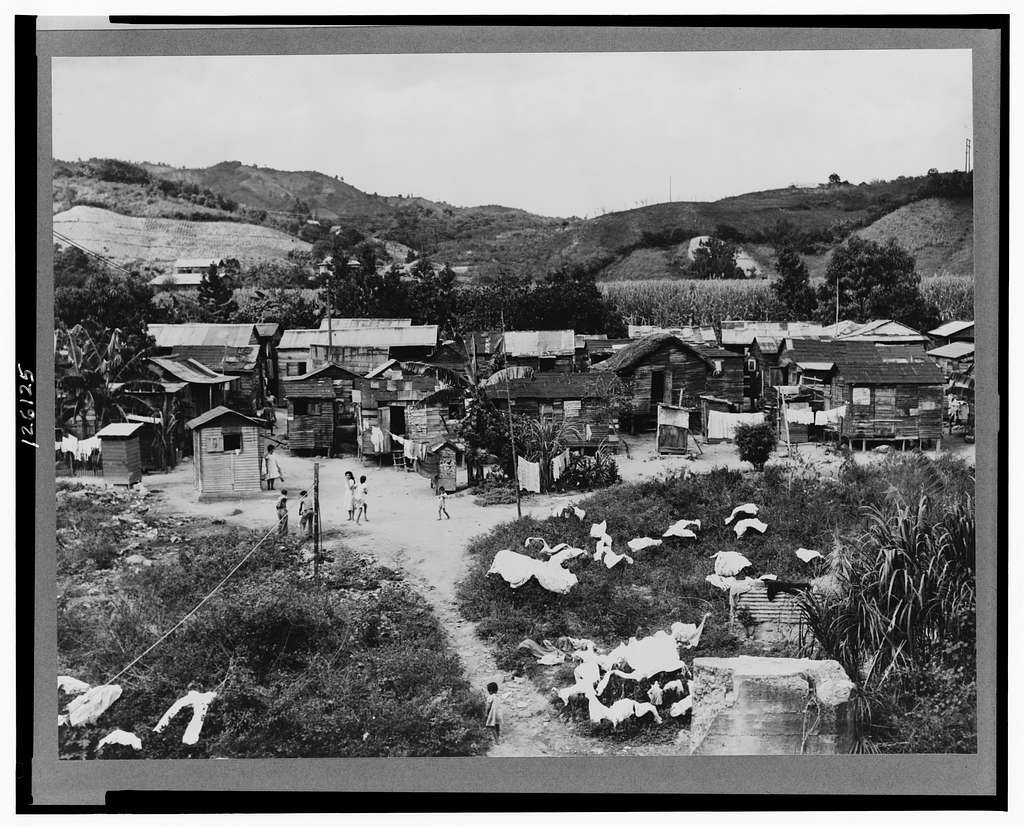

The novel’s authenticity stems from Pérez’s own story, having lived in Puerto Rico and grown up in Western Massachusetts in the same isolated town, Woronoco. Pérez acknowledges she knows the same Puerto Rican community the Rodriquez family lived in named Beehive. A name that stood for industriousness. Fitting as Andrea’s father, Don Luis, raised on a farm in the mountains of Utuado, Puerto Rico, knows hard labor.

By Jack Delano [Public Domain]

Landing a factory job at the Strathmore paper mill, the company also offered cheap rental homes. The mill and the Beehive are gone – the inspiration for the novel – but if you’re an artist or dabble in the medium, you know the company has endured.

The Rodriquez migration story depicts the primary reason Puerto Ricans left their homeland after WWII: the promise of jobs. Orchestrated between the Puerto Rican and US governments to reduce poverty levels in Puerto Rico while helping to fulfill America’s labor force needs.

Sprinkling Spanish words and phrases throughout the plentiful dialogue adds to the novel’s realness. Initially, you might stop reading to look up the English translations, which I did, until you realize if not spelled out you can often guess. Some words sound better in Spanish than the English slang or swear words; others don’t interfere with the storytelling. Their use also shows us how alienating you can feel when you don’t understand the language spoken.

As the controlling patriarch of this household, Don Luis brings a hard-working ethic and ultra-conservative values he demands of his kids. Out-of-step with American stateside culture in the fifties when children had free time to play games on neighborhood streets, ride bicycles, visit friends at their houses and invite them to yours. Andrea and Pablo are painfully cooped up inside watching their childhood disappear. Until they finally got bikes that gave them a taste of freedom and woodlands. Quite different, though, from their lush, tropical Caribbean island homeland.

The town mercilessly lacks public transportation, aggravated by Raquel not knowing how to drive. She didn’t need to in Puerto Rico, nor is she allowed to get behind the wheels of Don’s pride and joy: an Oldsmobile, quite popular back then.

A dramatic opening scene takes place inside that Olds: Raquel’s desperate-to-escape attempt to flee from her lonely misery. Endangering her kids doesn’t cross her mind. They don’t get far, to a nearby cliff, in this rocky terrain. The natural world delights two young, curious kids but it’s poison to a mother used to the ease of hopping on a public bus to do her errands and visiting. Raquel is miserable and unconcerned about making her family miserable too. In her early thirties, she still hasn’t figured out who she is at the expense of her children.

Her second attempt succeeds. Dragging her children, unbeknownst to their father, landing in Puerto Rico at Raquel’s stepsister Cecilia’s house. Scrapping by, Andrea and Pablo are starving, but they’re hungrier for a mother.

Cecilia is a modern-day woman who owns her identity. She identifies as a man, dresses like one. The children’s sweet innocence recognizes their Aunt is different, could care less, embrace her love, strength, resolve, mothering. They also warm our hearts as Cecilia’s skin is darker than theirs, her father a Black man. They don’t harbor any prejudice, but you’ll see others in the family do. The complex history between Latinos and Blacks is depicted too.

An orphaned boy who brings food and friendship to Cecilia, Andrea, and Pablo is also endearing. He teaches the siblings how to playfully enjoy the beauty of the island. Meanwhile, no surprise, Raquel abandons them again, for weeks and months, until they feel she’s not their mother. When she suddenly shows up, whisks them away to a dangerous neighborhood elsewhere in Puerto Rico, you’ll wonder if they’ll ever escape that nightmare.

Almost miraculously, they do. When they return to their father, his brothers and a sister have also come to the factory town, the men promised jobs at the mill. The importance of family and extended families in the Puerto Rican culture is captured. It makes a difference in the trajectory of Andrea’s life, but not Pablo’s. Considered to be the more intelligent of the two, but all the smarts in the world are wasted if you don’t apply yourself.

All good reasons Pérez’s novel was the first winner of Simon & Schuster’s Books Like Us contest.

Acceptance is an all-powerful theme. Tied to one’s self-image, part of the tough road to self-discovery and identity. Accepting who you are, as seen in Aunt Cecilia. Acceptance and then commitment to becoming who you want to be and what you want to do with your life in Andrea’s sacrifices and steadfastness. In Don Luis’ slow acceptance of Andrea’s life choices. Lack of acceptance of what you’ve done in Pablo’s case, and how there might still be a chance to accept and save yourself.

Yes, a winning story on how to overcome.

Lorraine