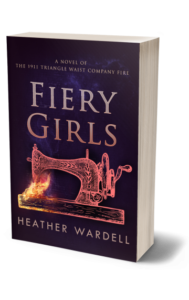

Young Jewish and Italian immigrant women making a difference (Garment District, NYC; 1909-1911): In her first foray into historical fiction, self-published Canadian author of twenty-two novels, Heather Wardell, has humanized early 20th century historical events and figures, forgotten or little known. Fiery Girls is a moving feminist story of the powerless fighting the powerful, of young immigrant women who once made the majority of clothing for women in America in NYC’s garment district, explaining why the city is considered either the leader or one of the Fashion Capitals of the World.

That glamour wasn’t the world of the early 1900s when this story kicks off. A world in which two sixteen-year-old girls arrive at Ellis Island within weeks of each other in August 1909: one painfully alone, Jewish, from Russia at a time of violent anti-Semitic pogroms – Rosie; the other, Maria, comes to America with her brother Vincente, Catholics from Italy. Both girls are expected to earn enough money to support their families. Rosie to help hers escape persecution; Maria to return home. How long will it take them making $2.00 a week?

The two girls couldn’t be more opposite: Rosie painfully self-doubting, Maria full of self-confidence; Maria the beautiful one who relishes the attention, Rosie the innocent one who shies away from it. Rosie who’ll live in a tenement house with strangers; Maria and Vinnie came with an arrangement to live with a family friend, in a house of six with no room for eight. The girls end up becoming good friends when their paths cross working at the same infamous garment factory where the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire occurred.

Warning: This disturbing five-minute video reenacts visually what the heart of the novel reenacts literally.

Maria is fiery, full of self-confidence. Fiery girls can do gutsy things, which you’ll see. (Vinnie’s role could fill an entire novel, as his laborious, dangerous work is helping to build the New York City subway system.)

When Rosie gets her first garment factory job, starvation wages and inhumane working conditions become clear. Moving from job to job, she lands at the catastrophic factory, at a time when young immigrant female workers mobilized to form the local union of the International Ladies’ Garment Workers Union, which led to the largest strike by women in American history. Lasting three months, it was known as the Uprising of the 20,000. Their mission epitomized by the tragic fire and loss of 146 workers, mostly girls and women, that broke out on several floors of the ten-story Ashe Building, located further away from the Lower East Side near Washington Square Park. Still standing, the building’s name changed to the Brown Building, at NYU.

One of the strengths of the novel is the way the author doesn’t rush historical events, enabling us to feel as if we were there. Part I describes the immigrant arrival and settling-in process. Chaotic and traumatic scenes at Ellis Island are immersive and for Rosie’s story based on an historical figure: Cecilia Greenstone, who meets “legs shaking” Rosie on page one to interpret her Yiddish language, critical to deciding if she’ll be allowed into America. (Maria and Vinnie studied English before they came over.)

via Center for Jewish History on Flickr

Jewish immigrants back then spoke Yiddish, so the prose is sprinkled with the language Jewish ancestors spoke. Words nostalgic to Jews remembering their grandmothers and grandfathers, likely to have also lived in the teeming Lower East Side in ghetto-like neighborhoods, perhaps believing America’s streets were “gold-paved.” Since one of the few trades European and Eastern European Jews had been permitted to do was sewing and tailoring, many garment sweatshops were located around their deplorable, cramped housing. Primed for a crush of skilled workers who’d propel an economy integral to the city’s culture at their expense.

Besides the historical interpreter who lets Rosie into the country, the oldest grassroots organization of Jewish Women in the US becomes her savior in the form of fictional character Julia. She meets Rosie on the Island to help find her a place to live and a job. Relieved she’s a woman since “men in uniforms never care about Jews,” Rosie later tells her that “if everyone is as kind as you, America “will be a wonderful place to live.” She’s about to find out that to make that happen she’s got to fight for it. This isn’t just her coming-of-age story, it’s immigrant history.

via Kheel Center on Flickr

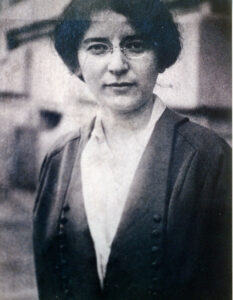

Fictionalized Clara, a union leader, is a charismatic force inspiring garment workers like Rosie and Maria, in different ways based on their fiery and reserved personalities. She’s based on the real Clara Lemlich who led the fight against a male-dominated industry where “a girl’s not allowed to have an opinion.”

Part II is the fire and aftermath. The fire scenes are masterly done over a number of chapters where time stands still (versus chapters alternating in the two girls’ voices and move forward in time). You can feel the sheer panic when the fire breaks out: the desperation felt when the female workers can’t get out because the doors are shut; the height of the closed windows on the floors they’re trapped in; the firefighters trying to rescue them and contain the fire. The suspense of not knowing if Rosie and Maria miraculously made it out.

Not all is gloom and doom. There’s nickelodeon entertainment and Steeplechase Park on Coney Island. Die-hard New Yorkers and visitors to the Lower East Side’s Tenement Museum will find their mouths watering at the mention of Yonah Shimmel’s Knish Bakery and Katz’s delicatessen that still endure, though little else does due to gentrification. Lost is the bustling, bursting atmosphere and spirit galvanized by communal hope and hard-living.

A word about the word shirtwaist, a term once used in the garment industry. It refers to a woman’s button-down blouse. Internet references compare it to a man’s dress shirt as it’s long-sleeved and can be white, but you can find plenty of fancier versions with puffy sleeves and feminine fabrics. Women were paid based on what piece of the shirtwaist they could sew, be it sleeves, “side seams and hems and buttonholes,” or “buttons and cuffs and lace or embroidery.” Pieces were paid based on difficulty; the more difficult and diverse, the more you were paid. Still, you might only advance to earning $5.00 or $6.00 a week, maybe $10 if you could excel at making the complete garment.

Midway through you may get frustrated with Rosie’s naivety, low self-esteem, and pinning her hopes on a “fella” she thinks is waiting for her back home. We must remember she’s only sixteen. Maria has a fella from back home on her mind too, but she doesn’t constantly question herself (far from it.) Be patient as the fire will soon consume you, as it does these two girls, co-workers and friends, making you realize Wardell intentionally showed us Rosie Before to appreciate her After.

The novel reminds us that while we wish history didn’t repeat itself, the 2000s story of the LA garment industry involving Asian and Hispanic immigrants tells us otherwise.

For countries around the globe who provide cheap labor for American goods, a recent fire at a Bangladesh garment factory is a gruesome reminder of the importance of fiery girls.

Lorraine