A graceful writer embraces the grace of the natural world and all its living creatures, counteracting what’s lost and vanishing (Nashville, Tennessee; 2022, and past years): As soon as you read a few pages of Margaret Renkl’s new essay collection A Comfort of Crows, you’ll feel calmer. Call it literary therapy, a quieting mind-set, a potent self-help antidote needed for a world when so many are grieving, suffering, struggling.

A poet for fifteen years before she became an essayist, Renkl’s poetic prose shows us the enormous comfort she derives from Nature and all its wild creatures; some we don’t see, others we disregard or stay clear of. Through fifty-two mini-chapters, week-by-week, season-to-season over one year in her own backyard, these intimate reflections, meditations, enlightenment, part memoir, part naturalist, reveal how deeply Renkl has internalized her daily life to the rhythms of Nature, truly “straddling two worlds.”

When Renkl writes about “landscapes of enchantment,” she’s not writing about the Land of Enchantment – New Mexico – that inspired the title of this blog and the value placed on enchanted prose. Instead, she’s sharing her observations, engagement, and lamentations of what’s happening on her half-acre of land surrounding her home of thirty years in Nashville, Tennessee, expanding her “miniature ecosystem” to the rejuvenating walking trails nearby. Here is where she and her husband Haywood, a teacher, she a former one and volunteer teaching English to refugees, raised three boys, all grown up and living elsewhere. Here they also “buried five dogs,” and “let an unaccountable number of fallen leaves lie in a life shot through with leavings.”

The leavings are ingrained in the book’s soul. Some leavings are raw: her mother’s recent passing, her emptied out home, entering her sixties, all causing Renkl to reflect on the passage of time and what matters most in a life well-lived.

Crows, highly intelligent birds, are greatly admired for sticking together as families, mourning the loss of one of their own. The prose conveys wistful, nostalgic, sorrowful emotions that resonate as our lives have changed so much over the past years, including the devastation of climate change – if we’re paying attention. Renkl wants us to pay attention, though maybe not as acutely as she does.

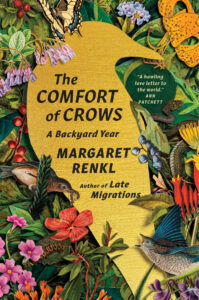

That’s why a Mary Oliver poem – “To pay attention, this is our endless and proper work” – is one of the epigraphs introducing this gorgeous book. Both the prose and the striking art accompanying each week created by her brother Billy, a fine arts “collage artist,” illustrator, and teacher.

Their sister-brother artistic relationship fascinates. This is the second time they’ve collaborated on a book. (See: https://milkweed.org/book/late-migrations.) The synergy gained by combining a sister’s poetic voice with a brother’s visual one deepens the reading experience.

Some collages are quite clear as to their earthly inspiration; others more mystical, conveying a celestial and spiritual reach-for-the stars impression. On Billy Renkl’s website you can see these images: https://billyrenkl.com/fine-art/the-comfort-of-crows/. Note how he explains the role of his artistic visions with the prose:

“The collages braid together three threads . . . the natural world as a source of curiosity . . . . astonishment and devotion, and as a model for understanding ourselves in relation to each other and the world.”

An artistic brother’s artworks are wondrously in sync with his sister’s prose, emotions, and spirit.

The harmony between sister-and-brother seems forged from the time they ran free in the woods where they grew up in Alabama. Those memories nurtured the author’s becoming, and gratitude for the wild world she repeatedly calls a “praise song.” The term can be viewed as biblical, secular, or existential in inspiring our purpose on Earth, expressing the beauty and fragility of all forms of life. Human and nonhuman.

An abundance of trees, plants, wildflowers, and wild species, seen and unseen, enchant the pages. Among them are tadpoles, butterflies, lightening bugs (when was the last time you saw those “flashes of brightness” light up the night? Renkl asks), crows, opossums, even the sighting of a bobcat!

The Author’s Note tells us that while the book’s subtitle limits the timeframe to one “backyard year,” Renkl has been penning thoughts over years. Makes sense, or how else could she punctuate so finely each week’s journal-like musings introduced by snippets of prose by so many contemporary authors and poets? A formidable task to have read all these books, finding the precise set of words to fit what she’s saying. Words from Claire Keegan on crows, Catherine Raven’s fox, Maggie Smith on animals, Camille T. Dungy’s soil, Ross Gay’s delights, Ann Patchett’s life in “constant revision,” Richard Powers on mourning what’s gone, for instance.

Renkl is extraordinarily attentive to all sorts of winged creatures. Some like hummingbirds and bluebirds she watches carefully from bird feeders hung in front of nearly every window of her house. The dangers of interfering with the natural world are discussed, but the food and shelter provided is reasoned by “natural systems aren’t natural anymore.”

Two bright purple flowers with alluring names – passionflower and beautyberries – and a hummingbird’s iridescent patch of feathers called a gorget that comes in a variety of colors including purple are examples of what’s in store to stir your senses:

Exuberance for Mother Nature is pure joy. The warmth exuded attributed to: “Age has given me an internal warmth.” But we know better. This is who the elegant writer is. You can pick that up in this video taken in Renkl’s backyard:

Renkl aims to infect us with the same love and gratitude for our natural environments and those we love. Hers has a higher purpose beyond observing and appreciating. She’s an eco-warrior, fighting to preserve what she can. She wants us to do that too, in our own backyards.

“More and more I ponder words like bounty and replete and enough. I think of what we are losing from the natural world and of what we will leave behind when we ourselves are lost. The trees. The stories. The people who love us and who know we love them, who will carry our love into the world after we are gone.”

When someone moves away from her neighborhood, Renkl is hit by the sound of heavy equipment tearing down their house, taking with it the fond memories she and her neighbor carry. Her quiet outrage is a yearning for people to stop building bigger, so contractors will stop knocking down trees and fauna, disturbing, destroying a piece of the natural world.

Eco-grief or ecological grief is a relatively new term describing the devastation climate change has wreaked on those who pay attention and care. An element of that winds through Renkl’s contemplations without sounding preachy. Her heartfelt sorrow is far from paralyzing. She’s dogged at finding, exalting, and contributing to preserving the beauty that still exists, or can with a little help, unfolding around her each season.

Margaret Renkl’s eloquence is a gift for all of us, elevating our passage through time.

This post will likely be the last in 2023. Not by accident. I wrote it a little while ago, but decided to delay until December. Because it hit the pitch-perfect tone of balancing all the grief and sadness of the year with an uplifting way to carry on that comes from the heart.

Warm wishes over the holidays. With thanks for reading with me.

Lorraine