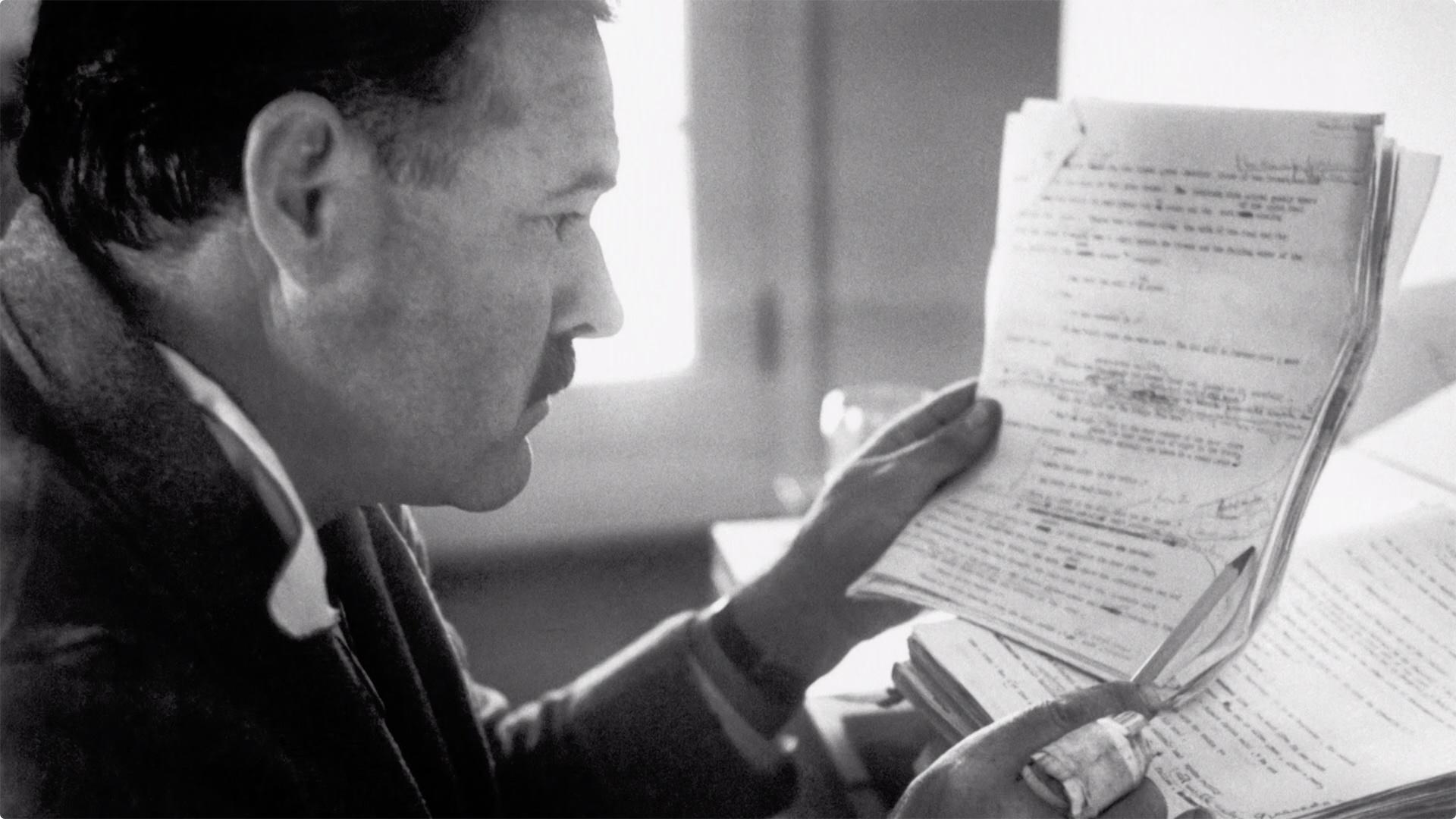

Still interpreting Hemingway (1923-1936 short stories set in Michigan, Spain, Italy, Austria, Africa; 1936-1944 historical novel spanning the Spanish Civil War, Winter War in Finland, WWII, Cuba): You’ve probably read at least one Ernest Hemingway novel sometime in your life, but have you read his short stories?

Legendary for writing prose as simple as can be, his sentences may seem straightforward but “important things were left unsaid,” explains acclaimed author Tobias Wolff, anthologist for this new collection of nineteen short stories that show why we’re still interpreting the meaning of Hemingway’s stories nearly a 100 years after he wrote them.

Wolff, who’s written his share of short stories, novels, and memoirs, including This Boy’s Life considered a classic, regards Hemingway “important” like “Winston Churchill, or John Wayne, or Mickey Mantle.” All historical figures “larger-than-life.” Poignantly, he remembers when and where he learned Hemingway had killed himself.

Wolff’s Stanford University profile, where he’s an English professor emeritus, lists thirty-five honors and awards, excluding receiving the 2015 National Medal of Arts. So when he tells us Hemingway was a “very complicated man,” we listen up.

These stories demand putting on your thinking caps. Some so short you’ll breeze through them and miss the whole point. Longer tales are equally open for interpretation, to such a degree Wolff doesn’t just offer his interpretations prefacing a particular story but chose other notable contemporary writers to join him such as Edna O’Brien, Tim O’Brien, Abraham Verghese, and Mario Vargas Llosa.

It’s fascinating to see how you may not agree with their analyses, but certainly welcome their insight. That’s because Hemingway intentionally left things up to the reader to figure out. His famous quote about writing one true sentence, doesn’t quite ring true in these stories; the cliché read-between-the-lines couldn’t be truer. Owing to Hemingway’s Theory of Omission, or Iceberg Theory:

“If a writer of prose knows enough of what he is writing about he may omit things that he knows and the reader, if the writer is writing truly enough, will have a feeling of those things as strongly as though the writer had stated them. The dignity of movement of an ice-berg is due to only one-eighth of it being above water. A writer who omits things because he does not know them only makes hollow places in his writing.”

This collection, then, is fresh and eye-opening; also surprising how profoundly sad many are. Until you pair it up with its companion documentary, a Ken Burns three-part PBS mini-series, Hemingway, that aired when the book came out. This double-review also morphed into reading what the best of historical fiction does: help us feel the emotional push-and-pull of a very complicated man.

Who better than Paula McLain, an early pioneer of the literary sub-genre of women behind the famous men? Her first historical foray into one of Hemingway’s wives (he had four) was The Paris Wife, when married to his first wife Hadley Richardson and they had his first son (he had three) nicknamed Bumby. Love and Ruin – what a perfect title!

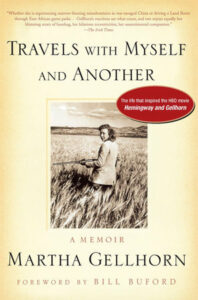

The novel takes us into Hemingway’s third marriage to Martha Gellhorn, a journalist whose literary ambitions were smothered by a man who thrived on grabbing all the attention. Later, she became a famous war correspondent – why the novel is such an ambitious undertaking – and a novelist, memoirist, and short story writer in her own right. Love and Ruin emotionally complements the stories, especially when the couple were both reporting on the Spanish Civil War, where they fell madly in love.

Hemingway fictionalized his stories from his life. So the more insight you have into Ernest Hemingway the writer and the man behind the public persona – the grandiosity and intensity of his needs, desires, and demons – the greater your appreciation for what’s said and unsaid.

His fondest memories were as a boy summering with his family in northern Michigan, kindling his love for the outdoors and sports. (On second thought, perhaps you’ve read his Nick Adams Stories? A few included here.) Other stories relate to Hemingway’s fighting in and covering wars, and his ardor for bullfighting and big game hunting.

McLain, like the Burns documentary, wants to show us his many sides. Why Hemingway was so complex: his cravings for constant love a hole that’s never filled; his manic-depressive mental state, with bouts of excruciating loneliness. He’s both loving and raging. His addictions are significant factors in his self-destructiveness. Martha is sensitive and sacrificial, yet he’s out-of-control revengeful when she finally decides come hell-or-high-water to leave him for weeks at a stretch, even months, on assignments for Collier’s magazine, so affected and committed to telling America about the suffering of refugees during WWII. So expect plenty of suffering in Hemingway’s stories too.

The Hemingway Stories challenged me. Love and Ruin captivated.

Loneliness runs through so many stories, sometimes accompanying excessive alcoholism. In Out of Season, the Italian hotel gardener is “quite drunk” in a story that seems to be about fishing, but actually has little to do with it. The old, handsome drunk who finds solace and compassion in A Clean, Well-Lighted Place is not without suicidal thoughts. (Hemingway’s father committed suicide too.)

Two stories are awfully bloody and they’re not about war. The Undefeated, “a great bullfighting story,” says Tobias Wolff, is also “touching” whereas Indian Camp is a horrific medical tale. It helps to know Hemingway’s father was harsh and a physician. Wolff believes Hemingway “handles very sensational material in an absolutely unsensational way,” but Verghese, a physician himself, is appalled at how “insensitive or hardened to the suffering” the character in the story is. Beware, it may turn your stomach.

Up in Michigan, the first story, may be the briefest but it gets under your skin. Written in 1923, it depicts how constricted women’s lives were and how relevant today. Perhaps set in Michigan because this place marks Hemingway’s innocence? Like the “neatest girl” in the story, Liz, with a crush on a man who barely notices her until one day he returns from hunting, starts drinking whiskey, and out-of-the-blue kisses her, strangely. Disturbingly. She’s sitting on a chair and his kiss isn’t gentle, nor the way he grabs her body. Their dialogue is spare so you must read into the narrative to decide whether she even knew what she was getting into. Hemingway captures her innocence with, “Something clicked inside of her and the feeling was warmer.” Then her ambivalence? Fears? Wishes? saying, “Don’t, Jim.” The story shows how difficult it is to prove rape – my interpretation. Not what Edna O’Brien, “Ireland’s greatest living writer,” says:

“Many women feel that Hemingway hated women and wrote adversely about them. I would ask his detractors, female or male, to read this story. Could you in all honor say that this was a writer who didn’t understand women’s emotions and hated women?”

Some authors comment on their favorite story. Mine, The Snows of Kilimanjaro, is the last in the collection. War veteran O’Brien says it’s probably his favorite too, along with Verghese because of how “in one short story a man can so effectively have his own life flash before him.” Here you’ll find Hemingway’s lyricism: “The snow as smooth to see as cake frosting and as light as powder.” Here too is: “I loved Africa,” says Harry, the character who “loved too much, demanded too much, and he wore it all out.” Like Ernest Hemingway.

Lorraine