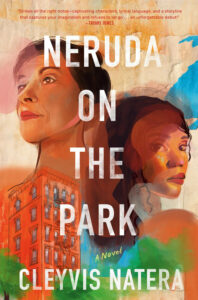

Gentrification – what it feels like and does (Upper Manhattan, 2015-ish): Fifteen years in the making and it shows. You will not be able to put Neruda on the Park down.

Fifteen years to establish Cleyvis Natera’s fantastical goal, stated in her Acknowledgements: to “let our stories change the world with the power and beauty of our imagination.” Fifteen years to imagine an exquisite, fiery immigrant’s tale reflecting the realities of how Natera and her Dominican Republic family “survived” the “immeasurable pain, loss, joy, and love as immigrants in the United States.”

Immigrants who carved out a new home in the one city in the world that has more Dominicans than anywhere else outside of their Caribbean island homeland – New York City. Specifically, in the upper reaches of Manhattan near Washington Heights, dubbed “Little Dominican Republic,” north of Harlem, in the area where the author grew up since age ten.

Fifteen years pouring her literary heart and soul into a place, its people, community, and culture inventing a neighborhood – Nothar Park – and two unforgettable characters: twenty-nine-year-old, Ivy-league educated lawyer Luz Guerrero, and her mother Eusebia, the loving force behind her. Calm father Vladimir loves his family too, a policeman on a manhunt upstate so he’s gone during much of what heats up between mother-and-daughter. Growing tensions on several bombshell fronts frame the gentrification plot: what it means to be told to “Go Home” in more ways than one. How the color of your skin influences and energizes, good and bad, who you are, aspire to be, and who you become.

The best way to describe how this high-spirited novel reads is to imagine you’re on a train that feels like it’s going too fast along the subway tracks of NYC. Three major events have converged, so you’re aware it’s not going to stop at your destination, acting like it has a mind of its own. In this scenario, three minds going in different directions. Luz and Eusebia on the verge of breaking ranks in terms of where they want to go, though neither knows where their destinies lie. Luz has felt a floating “emptiness” and “loneliness” for a while; Eusebia has newly decided if no one else is going to stand up, she will. The third mind is far more powerful: the developer determined to execute his fantasy. Bigger than any urban project ever built.

You’re in the hands of the driver of the train – the author – who’s had plenty of time to decide and command her train how far she wants to take it. The atmosphere inside the train is filled with the voices, love, passions, yearnings, struggles, sacrifices, and pride of passengers who’ve come to America from the same impoverished Dominican country for the same reasons: to make a better life for themselves and their loves ones. They include neighbors and friends, who like the Guerrero family, brought reminders and symbols of Home with them: rhythmic, genre music and dance (Meringue, Salsa, Bachata, Son); sweet, spicy foods (habichiuelas con dulce, pollo guisao, pasteles) that can take hours to prepare out of love; and their nation’s blue-white-and-red flags hung on windows and draped over the fire escapes of their brownstone apartments.

Everyone on this train is in it together, so they’ll be embroiled in the fires the Guerrero family ignites (Eusebia), wants to put out (Lutz), while Vladimir (supported by Luz) has been working on an entirely different plan – dreamy – kept secret from the one person who desperately needs to be told.

The train hasn’t moved when the novel opens, but its rumbling. The noise is louder than what you’ve grown accustomed to hearing in one of the noisiest cities in the world. The “wrecking ball” described in Chapter One, subtitled, “White Out, Washed Out,” prophetically announces the set-up.

Gentrification: a fancy word that means forcing out the urban poor to make room for the wealthier and privileged.

The piercing sounds of the “demolition” – “the sound of split wooden frames, shattered glass windows, and fractured brownstone” – are the thunderbolt that marks the onslaught of lives turning on a dime. Profoundly expressed in one of the two quotes in the epigraph:

“Who would have said that the earth

with its ancient skin would change so much”?

Selecting words from Chilean poet Pablo Neruda’s poem “How Much Happens in a Day” – his “Love Poems” meaningfully popping up elsewhere in the novel and obviously inspiration for the title – speaks to Natera’s boldness. Well-aware the legacy of the winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1971 for “poetry that with the action of an elemental force brings alive a continent’s destiny and dreams” has been tainted by his own admission of rape, she doesn’t shy away from his prescient words. Instead, she crafts a stirring commentary about what can happen so quickly when people feel utterly powerless even when they’ve played by the rules. For the Guerrero family, that’s twenty years making NYC their home.

Aimed at provoking the economic, social, and cultural forces that have sought to oppress the Latinx community spectacularly, gentrification at the center of this storm is spectacularly real. Because today sitting across the street from fictional Nothar Park is the behemoth development called Hudson Yards, which broke ground after 9/11, finished in 2019.

You’ll hear that “wrecking ball” in all three Parts of the novel – “Demolition,” “Excavation,” and “Grounding.” The erasure of yet another NYC ethnic community starting with the richly diverse Lower East Side, Nothar Park is the last in Manhattan. The Yards represent the epitome of what happens when you have billions and don’t care about destroying lives and the soul of what once made the city magnificent, bursting with color and character.

The author pays tribute to her own mother in the second quote in the inscription:

“Remember – you are trunk, not a branch”

(Regina “Masona” Lucas)

Remember it as Luz’s story evolves. Opening when Luz is exuberant, headed to meet her elder Latino role-model/mentor at the law firm she’s devoted seventy hours a week to for five years. At the so-called Special Place restaurant, she orders champagne for breakfast anticipating her heads-up on becoming partner. Only to find out she’s actually going to be let go! Even though she’s done everything right. Shocked and humiliated when her estranged, childhood best friend Angelica overhears the conversation waitressing at said private spot, spreading the news to her mother’s bingo-playing neighborhood close friends called The Tongues because they’re so gossipy. Her devastating secret is out, but Luz hopes Eusebia doesn’t find out until she finds the right time to tell her. The tension between former best friends who chose different paths after high school is thick; Angelica is part of the neighborhood, so the two bump into each other. When she asks Luz if she thought she was fired because of discrimination, initially Luz denies the possibility. Why?

Around the same time, Eusebia has an accident with consequences felt throughout. You’ll think you’ve figured out her problem. You’ll guess wrong. Combined with the backdrop of a violent act towards one of their precious, young own, this novel is about people and a community at the “cusp” of something monumental.

Accompanying the richness and passion of a culture, a steamy romance develops, too quickly like the other events, between Luz and a white man who embodies everything going wrong, aptly named Hudson. Their relationship burns brightly too, but we sense something isn’t going in the right direction as well.

Don’t stand on the noisy platform when this train arrives. Hop on. Take the ride. Because it’s going someplace you’ve likely never been before.

Lorraine