Nurture vs. Genetics and other mysteries of life (Manhattan & Long Island, NY and Cambridge, MA; 1950s to 1968): Like a three-act play, Margot unfolds theatrically.

Probing many issues, asking many thought-provoking “What If” and existential questions about the meaning of life, Margot, historical fiction, can’t be pigeonholed.

Shaped around Margot’s unsettling coming-of-age story – a searing search for identity and belonging, battling achingly low self-esteem amidst the changing social and cultural forces of the fifties and sixties, along with an early, belittled fascination with science – Margot is a psychologist’s feast. Raised in a loveless, emotionally abusive family of Old Money white privilege and prejudice, her sad and lonely trajectory swings submissively, feverishly, passive-aggressively.

Margot presents as many things too. Can she ever recover from the relentless “fault-finding” of her cold-as-a-fish mother Peggy, the emotional abandonment believing she’s the one always wrong?

The moody cover sets a disquieting tone. Told in three parts: “Beginnings” (Part I/Act I), her choke-hold, formative childhood and adolescent years; “Intermediate” (Part II/Act II), her breaking-out college years – the burning core of the novel; and the haunting ending, “Advancing” (Part II, Act III), the mood is “doomy-boomy.”

Provocative, Margot will surely elicit varying reactions and thoughts. Not, though, when it comes to the originality of the prose. Wendell Steavenson’s writing holds us hostage evoking what Margot’s family did to her. Playing with snappy combinations of words, she intentionally overuses hyphenated words, creating drama, zippy pacing, laser-like focus. Words are also repeated without punctuation for emphasis – “studied studied studied” (Margot’s head always in books, her “favorite people”), and “ran ran ran all the way home home home without looking back.” Cynical, the rapid-fire dialogue reeks of sarcasm.

No warm and fuzzy happiness. At best satisfaction and acceptance. So why would a novel screaming disenchantment fit so well with Enchanted Prose? The best explanation I’ve uncovered so far comes from an article adopted from a new book, Out of Silence, Sound. Out of Nothing, Something by Susan Griffin in which she says: “If the sound of your words is true, your reader will be riveted if not enchanted.”

The What Ifs begin before you open the book. What If author Wendell Steavenson had a different career? Would she have written a gentler, happier story? Steavenson, a war correspondent, has witnessed the senselessness and trauma of conflict in some of the most dangerous hotspots around the globe. Having written three notable nonfiction books set in revolutionary times in Iraq, Egypt, and Georgia (post-Soviet), expect those presumably life-purpose perspectives in Margot, her second novel. (Paris Metro, her first).

The What Ifs kick off on page one, when eight-year-old Margot falls from a “rope ladder” dangling from her treehouse. Instead of her small-minded mother appreciating that her wonderfully curious and intelligent only child can find solace and joy in the natural world, Margot fears she’ll be “mad at me for gallivanting.” Soon her mother’s “brittle-voice” will repeat her mantra that Margot will never be “good-enough.” When that’s pounded into your head, what does that do to a young girl’s sense-of-self?

What If her hiding-in-the-library nursing apple-brandy father Harrison gave her any attention? Absent are any real mother-daughter or father-daughter relationships.

What If her wealthy family wasn’t in the 1% and thought only money equaled happiness? They own two homes: one on the richest avenue in the world, Park in Manhattan, and the more vivid setting, the “big house,” an estate on Oyster Bay, Long Island. (Teddy Roosevelt summered here; today Sagamore Hill National Historic Site). Would they treat her any differently if she was growing up today?

By Jo Zimny Photos on Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0]

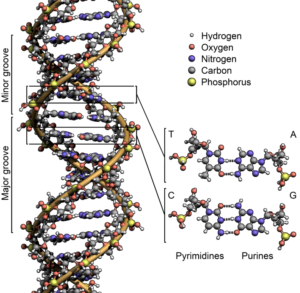

Two different types of revolutions in the “hippy-dippy” sixties take center stage: the Sexual Revolution and the Women’s Movement. Sharpened by Margot’s choice to attend the all-women’s experimental and rigorous college Radcliffe, before it merged under Harvard. Heightened by her captivation with Molecular Biochemistry after Watson and Crick made their discovery of DNA. Margot is gripped by the possibilities of cellular life on this planet after America landed a man on the Moon.

via Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 3.0]

Margot herself is an experiment. Desperate to liberate herself from the shallow, prescribed world her repugnant mother turned into a “head-game.” Magnified by an edgy time when women were liberating themselves sexually, Margot turns into a “head-game” for readers.

“What are we going to do about Margot?” is a refrain. Bright, socially awkward girls who shoot up to six feet tall are not marriage material as far as uppity Peggy is concerned. Marriage is all that matters when money rules the world. The family’s history is also marked by antisemitism involving Margot’s Aunt Sarah, her mother’s long-lost sister. A mystery that unravels bit-by-bit. It’s not beautiful, but it fits beautifully with what it says about Margot’s family’s intolerance. The loss of Sarah, who might have filled the emotional vacuum, emphasizes Margot’s yearning for “tenderness” yet rarely finding it.

Margot is “weary-wary” up against pernicious limitations then disorienting freedoms. Socially, her young life was filled with too many unlikable characters forced on her, setting in motion others who’ll hurt her. Two exceptions: one who rescues Margot’s wild, perhaps only girlfriend Maddy/Mad, and the standout Sandy Full, aka Sandyful. Full of sensitivity, kindness, allure. Margot met him when he’d graduated from West Point and she was about fifteen. He’s in and out of her life as he’s Stevenson’s eyewitness to war. Doing his patriotic duty for the US Army as the Vietnam War rages, he profoundly knows what sacrifice, loss, and physical pain mean. Perceptive to Margot’s emotional pain, he tells her “the trick is to look at the world with your own eyes.” Can she?

Margot is in and out of her own life too. Thrusting her into the radical, groundbreaking mission at Radcliffe – a “messy experience” in general, and specifically in a highly unusual genetics class where Margot’s male classmate calls her the “Princess of the Chromosomes” – sets up a perfect storm. Far from being treated as a princess, she’s torn between studying studying studying and inserting herself into a foggy milieu of partying, drinking, sexual promiscuity, pot smoking. Margot muddles through – unsecure, confused, distressed, burdened by her trademark shame, yet sometimes she’s excited and hopeful. Push-and-pull. Heady times.

The “Pill” is seen as a powerful trigger in freeing women sexually. Steavenson strikes at the hot button struggles in the current abortion rights ban and women’s freedom decades later.

To highlight how women don’t get their due, Rosalind Franklin’s name pops up. She worked with Watson and Crick, instrumental to their genetics discovery, but never got the credit. Her story may be famous in science circles, but most of us never heard of her. An article in The Guardian poses whether sexism was the reason this British chemist was left behind? An example of how thoughtful Steavenson was in crafting Margot’s story.

Margot, then, is often pictured with her head looking down into a microscope. Or, a centrifuge or an oscilloscope, studying the “protophase metaphase anaphase telophase” stages of mitosis. “The division of a cell is a beautiful and mysterious process,” thinks Margot who sees “something romantic about laboratories at night.” Even romantically she thinks scientifically: “Is it chemistry or electricity that quickens a heartbeat?”

Sandy offers what may be the novel’s most hopeful message: “Everything causes a scar, visible and invisible” . . . we can never erase our pain but we can honor it and we can learn to redirect it.” Again, can she?

Lorraine