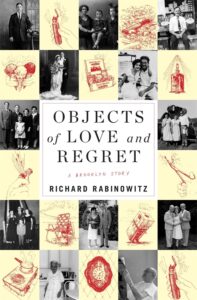

How everyday objects can mean so much (Northeast Poland, Odessa Ukraine, Lower East Side of Manhattan, Brooklyn’s East New York, & Deerfield Park, Florida; 1920s – 2015): If “our lives are a dance with history,” then Objects of Love and Regret leaps off its 300 evocative pages.

One of America’s “leading public historians” Richard Rabinowitz has taken an unusual perspective on “survivors and strivers” in his stirring, multifaceted memoir. Doing what he does professionally, curating American museum exhibitions, he uses ordinary objects to tell extraordinarily meaningful stories on the complex forces and psychological consequences of history, trauma, economics, cultural values, and societal norms that profoundly shaped his family over the 20th century.

This is, and is not solely, a Jewish immigrant story. It’s a book that has something that resonates for everyone. Surprising in scope, memories, and takeaways.

Rabinowitz’s search to better understand what his East European Jewish parents went through coming to America in the late 1920s is especially focused on the “singularity” of his mother Sarah. Having survived Soviet “pograms” that killed “nearly a hundred thousand Jews” in Poland and Ukraine, the book is both a heartbreaking, terrifying story of anti-Semitism from a 100 years ago that alarms us today as bigotry towards Jews is surging. It’s also a Jewish immigrant story seeking “freedom and independence,” enduring tremendous poverty and hardships that more broadly applies to all immigrants when they come to America to escape persecution. Which is why Rabinowitz has the greatest admiration for Sarah as the “bedrock” for his family who nurtured a “House of Hugs.”

The objects that trigger and organize the chapters mean these dances are “touchstones of love,” not just “loss [that] leaves us with lifelong regrets.” One of the biggest takeaways, beautiful and poignant in light of the pandemic, is the concept of “Enoughness.” Sarah embraced it in everything she did. It’s a Count Your Blessings attitude. Gratitude for the things we have. Clichéd, but when you feel and see how life-affirming this positive mindset can be it causes you to reflect.

Calling himself a “microhistorian,” Rabinowitz shows himself to be a mensch: “a generous and thoughtful adult.” One of many Yiddish words that pepper the narrative that add richness to the prose. A literary dance. There’s something about Yiddish words that deepen the meaning of English ones, particularly when the author translates most of them. Which speaks to how much Rabinowitz wants us to take in the deepness and power of emotions.

As Rabinowitz digs into the emotional meaning of the stories behind the objects, he acts like a psychotherapist. In fact, four psychologists were consulted and acknowledged.

Arriving in America from a Polish ghetto or shtetl – a Yiddish word that refers to a village and a ghetto, in this case Wysokie–Mazowieckie, to live in the tenements of the Lower East Side of New York City was a different type of ghettoization. Is it any wonder then that one of Rabinowitz’s human rights exhibitions was designing the Tenement Museum in Lower Manhattan? Today, an emotionally affecting reminder of life primarily for early Jewish immigrants (Italians and others too) in the US.

Is it any surprise that there was no room in Rabinowitz’s house for racism? Or, that he also designed museum exhibitions like the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute in Alabama and the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center in Cincinnati, Ohio?

Sarah was a balabusta. A “highly competent homemaker” who “ritualized” cooking to the point of it becoming “holy.” Her “lifelong distrust of rabbis, born of a close familiarity with the domestic lives of the religious authorities in the shtetl,” symbolic of how impoverished, discriminated, and segregated people preached to by people of privilege felt, she devoutly practiced a form of secular religion preserving her cultural heritage through cooking, with her mother Shenka nearly literally tied to her apron’s strings. The kitchen and comforting meals the center of the life they made makes this also a moving generational story of motherhood. A joined-at-the-hip dance about the meaning of Home.

So when Rabinowitz discovered in 2015 a faded, green-painted bottle opener Sarah bought for Shenka from a pushcart peddler on the Lower East Side for twenty cents, haggling from 25c, in 1934, the simple tool that could easily have been tossed away made him realize this wasn’t “really about kitchen work” but “about the bond” between mother-and-daughter. “What had produced this closeness?” Rabinowitz explores.

Particularly poignant when contrasted against Rabinowitz’s father David, who went from one job to another and cycles of unemployment, worsened since he saw his life’s purpose as providing for his family. For decades, he suffered from a low sense-of-self.

Sarah is the “Empress of Empathy,” steadfast in weathering an intricate dance of economies spanning years of lows, some highs, and everything in-between. Good times came when David worked for the war effort as an electrician, and then a jeweler in the Diamond District of Manhattan.

Examples of some of the objects’ storytelling: “Papa Doesn’t Know from Ice Cream” is about “one of the first battlefields for the clash of old and new cultures” when Sarah eats her first ice cream cone costing 3 cents at twelve, newly arrived in America in 1928. “Isaac Guss Finds an Artillery Shell” is about Rabinowitz’s maternal great grandfather who perished during the Polish-Soviet War of 1919-1920, which even the historian “knew nothing about.” A cigar box tells the story of tenement life. How you could have so little and yet stored inside this cardboard box you saved small things as if you had a lot.

A cobalt-blue bottle of perfume romantically named Evening in Paris depicts a very different side of Rabinowitz’s father. “Dave Splurges” when he has so little money is about a twenty-year-old in love, who despite being poor, did so elegantly; his nineteen-year-old bride always attentive to how she dressed. No matter how poor they “did not feel themselves excluded from the better things in life.” A dance of pride.

By 1948, the family saved up enough money ($13,000) to buy a two-story rowhouse in the Brooklyn neighborhood of East New York near Jamaica Bay. Under 1,000 square feet, it represented the “American dream.” Though they still lived a fairly insular life, shared with Italian immigrants, really knowing your neighbors who looked out for each other meant you didn’t feel isolated anymore. The once ubiquitous aluminum folding “beach chair” isn’t about beaches but about grabbing a chair and parking yourself on the sidewalk in front of your home chatting with a dozen other families. Tight-knit neighborhoods, when mothers stayed at home and your neighbors’ children were in and out of each other’s houses, shows us what was lost.

Many other objects summon nostalgic and sad dances. Like the creamy Charlotte Russe New Yorkers loved versus the mailman’s whistle alerting a loved one died during the war.

Objects of Love and Regret is and isn’t just A Brooklyn Story or a New York story. It’s America’s story too, transforming over the last century. Transforming today, right before our eyes. Sending a timeless message: Remember what you have, and what you’ve lost.

Lorraine