Seeking justice to prove and reclaim 18th century art masterpieces stolen by the Nazis – a true art detective story (France, Germany; 2014 – 2019): Had it not been for a chance encounter and a whispered word, Paris’ Baer de Perignon would not be picturing her great-great grandfather’s “imaginary museum.” Nor absorbing us into her impassioned, all-encompassing, deep dive into researching ten of Jules Strauss’ paintings, an “early collector of Impressionist art”:

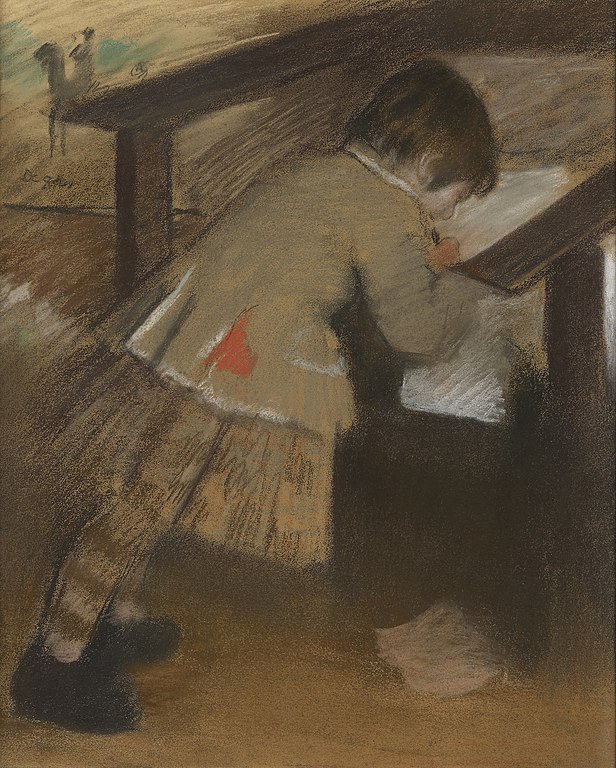

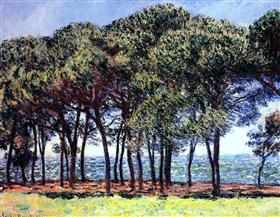

“If I close my eyes, I see walls hung with paintings. Portraits of lords and ladies of the eighteenth century court rub shoulders with Degas’ dancers, Monet’s glowing landscapes, Sisley’s snow-covered gardens.”

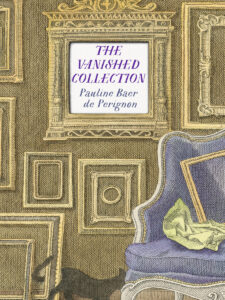

The Vanished Collection is a fascinating inside look at one family’s “paradise lost” because of a madman’s obsession and looting of 600,000 paintings during WWII, with 100,000 paintings yet recovered. A hidden maze of a “small underworld of the art world intermediaries and scavengers.” The theft of Jewish art is yet another aspect of Hitler’s atrocities, profoundly emotional, stealing “paintings of happiness” – the only possessions left connecting a family to its ancestors.

Reading like an engrossing international art detective procedural without any method other than following every lead, this complex quest sought to dig up the truth about ten of Jules’ masterworks her great-great grandmother Marie-Louise claimed were stolen by Hitler’s regime. “When it comes to art, only one thing counts: the pursuit of truth,” Jules Strauss wrote in 1931. A “hunt for the truth” that plunged Baer de Perignon into the “abyss of the past, where everything is opaque and complicated.”

Although Baer de Perignon co-wrote the screenplay for a documentary on the Nuremberg Trials and teaches writing workshops in Paris using art to elicit emotions, she tells us she knows “nothing about art history or painting.” Not anymore after what she goes through.

Genealogy plays a role in this daunting puzzle, which raised questions as to how Jules and Marie-Louise managed to stay alive, speculating trading art for survival. A helpful family tree going back four generations prefaces the narrative.

How did this journey start? By accident, when the author bumped into her “elegant” cousin Andrew born in England she hadn’t seen in twenty years at a concert by a Brazilian composer and guitarist (and political activist) both are fans of, Caetano Veloso. The song mentioned is Cucurrucucú Paloma, a melancholy ballad of memories and loss that evokes the mood of the memoir except for splashes of excitement when Baer de Perignon stumbles onto something. Veloso’s music is sentimental:

Although the author’s ancestors were Jewish, she was raised Catholic. Her father, gone twenty years, converted to Catholicism when war broke out and married a Catholic woman. Until she went down this art detective tunnel she hadn’t thought about her Jewish roots, particularly because no one talked about the war.

Meeting Andrew is not the whole meant-to-be story of how the author became emotionally invested in what happened to her great-great grandparents and their precious art. Words matter! When Andrew whispered into her ear about a “shady” Strauss auction the word led her into the art world’s essential work: provenance research, pouring through a mass of documents in archives and reaching out to art historians, dealers, gallerists, other provenance researchers, and drawing on family and friends to enlighten and fill in the blanks. Proving with “hard facts” the ownership of art is dense, intimidating, messy, disorienting, chilling, painstaking, exhausting, heartbreaking – and fascinating work. A few days after meeting Andrew, he sent the list of ten paintings that were the focus of her research. Including, I believe, these four:

The Star: Dancer in Pointe by Degas, Stone Pines, Cap d’Antibes by Monet,

Via Wikimedia Commons

It’s logical to start by talking to your relatives to see what they know. Andrew’s father, Michel Strauss, Jules and Marie-Louise’s son, was a legendary figure having headed Sotheby’s Impressionist and Modern Art department at its London headquarters for forty years. Retired, eighty, and still living in London, initially she feels intimated by who he is, later discovering he was as discrete as his father, so she doesn’t approach him first. Michel comes alive so discovering he passed away in October 2021 adds another level of loss to this moving story.

Baer de Perignon began by asking her father’s sister, Aunt Nadine, also eighty. She lives close to her, has lived in the same Paris apartment for sixty years presumably seeing a lot, and she’s close to this dear soul but her memory needs jogging and her niece is sensitive to bringing up painful memories.

Baer de Perignon is the mother of three young children. For a while, she finds herself dropping them off at school and then taking the train to a suburb outside of Paris, La Courneuve, to the Looted Art Archives at the Musée des Cultures Légumières Foreign Ministry’s Diplomatic Archives Center. Twice a day, she passes Drancy, the site of the main concentration camp in France where 70,000 Jews were slaughtered. (Total of 26 camps in France.)

She also searched the archives of “the world’s largest museum in the world” – the Louvre – where she meets and befriends Emmanuelle Polack, whose father was an influential French art dealer whose collection was also looted by the Nazis, Paul Rosenberg. Polack’s influential too as she identified ten paintings in the Louvre the Nazis stole. Polack travels with Baer de Perignon to help her conduct research at the La Courneuve archives, reminding her that “research takes time.” When the author ventures to the German Federal Archives the process is even more tedious, since she doesn’t speak German, nothing is digitized, and the old handwriting is written in a nearly unintelligible “Gothic-style.” The archives in the Musée d’Orsay, once a palace in Paris, were also consulted. All in such imposing buildings, they elicit a sense of hopelessness given their grandeur and so few researching. The most “painfully slow and arduous” among them all are government roadblocks and museums not wanting to let go of their masterworks.

Along the way you’ll learn more Nazi history than you knew before. A striking example is a French resistance heroine most of us never heard of: Rose Valland. She worked at the Jeu de Paume art gallery Hitler turned into a massive warehouse, secretly recording everything stolen. What comes as a surprise is how key Valland was to the discovery of an enormous cache of Nazi art looted that you may have seen in the movie, perhaps read the book, Monuments Men. The Monuments Men Foundation is committed to the restitution of what should rightfully be returned to families. Not surprising is the wealth of information in the Rose Valland archives.

Two other persons of note who helped: Patrick Modiano, the French writer whose novels are set during the Occupation. He lives near the author and they’re friends. In 2014, he won the Nobel Prize in Literature “for the art of memory with which he has evoked the most ungraspable human destinies and uncovered the life-world of the occupation.”

Award-winning translator Natasha Lehrer also deserves mention since she brought this remarkable story of one family’s paradise lost to us.

Lorraine