The existential scars of oppression and the wellsprings of activism and change in modern Ukraine (Lviv, Kyiv, & Uzhhorod, western Carpathian region; 1990s): Ivan and Phoebe isn’t an easy read. But it’s an important one.

A read to remember, not to forget. Soulfully aimed at, “hoping that the world will hear us and gasp at the beauty and the sadness” – the poetic words of awards-winning Ukrainian writer/poet/scholar Oksana Lutsyshyna from one of her poems.

What Ivan and Phoebe does is challenge us, makes us think. Makes us want to understand. Translated books are more difficult, as the history, culture, traditions, language are unfamiliar to us. All the more reason to read this no-holds barred examination of a country besieged by horrific wars, oppression, human rights denials, poverty and economic insecurity – yet today leads the world fighting for Democracy.

Where does this remarkable resoluteness, resistance come from? “What kind of people were these dissidents that neither prisons nor labor camps could break them?” What about those traumatized? The novel is a powerful study of contradictions. Nothing is straightforward nor guaranteed.

Viewed through the lens of Ukraine’s long and complex history, how does a young marriage survive when it seems doomed from the start?

If Ivan doesn’t even know his own country’s history, how much do we know?

Ukraine’s history matters, but you don’t have to google as many references as I did (how can a reviewer share her thoughts without doing her best to understand?) to viscerally feel the tensions, conflicts, themes. Stunning prose unlocks the door for entering and becoming immersed. You won’t want to turn away, even if you wish there was more beauty than sadness.

The novel’s structure sets up the darkness in store, with a “pinprick of light”: Part I, “The Gloaming,” Part II, “Revolution,” Part III, “The Choir,” striving to reform/transform when there’s so much “leftover from the Soviet days.”

Lutsyshyna is also a professor of Ukrainian Studies and Comparative Literature at the University of Texas, in Austin. Citing Ukrainian poets and writers, and others from elsewhere, she brings unexpected pleasure in elevating the arts, predominately literature and poetry. For persecuted people, inspiration and hope in seeing life can be better and offer ways to endure.

Photo by Adam Jones from Kelowna, BC, Canada [CC BY-SA 2.0]

via Wikimedia Commons

Ivan and Phoebe won the prestigious UNESCO City of Lviv Literature Award and the Taras Shevchenko National Literature Prize, honoring the Father of Ukrainian Modern Literature whose influence spread around the globe.

Symbolism abounds. While all reviews are interpretations, Ivan and Phoebe stretches the imagination. This one warrants a caveat: you may see things differently.

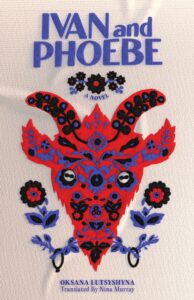

The striking cover seems to capture the plot’s trajectory of trying to bridge the gap between the Old and the New – from Soviet rule until 1990 to Ukraine becoming an independent country in 1991. The design seems to depict the transition. Embroidery, an example of Ukraine’s traditional craftsmanship, connecting to the importance of goats, from conventional goat farming to entrepreneurialism (making profitable goat cheese.) Ivan’s brother-in-law, Styopa, represents this spirit and resourcefulness. Or in the quoted words of Ukrainian dissident/poet/writer Vasyl Stus, Styopa seen as “adjusting and filling-oneself-with-oneself.” Dangers seen in that too, one that shocks.

Why give Ivan and Phoebe equal billing in the title when its Ivan’s voice we predominately hear? Phoebe’s silence – except for two caustic outbursts told in two free verse monologues – signals a feminist perspective defying a woman’s place was to only hold up the home. (Not now, when women are on the frontlines defending Ukraine against Putin’s War.)

About to be married when the novel opens, their marriage is a case study of what goes wrong when love isn’t assured; when parents/society pressure you to become a man (Ivan); when one partner has other aims in life and isn’t given the freedom to pursue them (Phoebe).

The marriage adds another “tectonic” layer to an already stacked tale that digs into the meaning and purpose of life. “Meaninglessness,” “uselessness,” “hopelessness” versus finding meaning, purpose, and hope through rallying against tyranny in a country battling for independence over a century. While the focus is narrowed down to the birth of Ukraine’s modern era in the revolutionary 1990s and the aftermath, it’s still complex and plagued by depravation, corruption, exhaustion, and who’ll have the will to carry on what was begun?

The married couple live under Ivan’s mother’s roof. Margita, hardheaded, dominates. Whatever you think of her, she’s as “immovable” as some of the student protestors Ivan gets mixed up with when studying IT at Polytechnic National University in Lviv. Ivan’s father, a heavy drinker, “flattened by life.” When Ivan wonders, “How does a man choose to remove himself from the world?” he shows he badly lacks self-awareness that expands to Phoebe’s needs. The novel paints a nation’s struggle for identity, Ivan and Phoebe’s too.

Phoebe’s real name is Maria. Named Phoebe, after Phoebus we’re told, the Greek goddess of poetry. Phoebe yearns to be a poet but Ivan doesn’t understand why homemaking and motherhood wouldn’t satisfy her. Margita has zero use for poetry, as there’s so much work to be done.

Phoebe’s poems hit a nerve with Ivan. Seems to date back to his university days where he met “red-hot” Rose, poet and activist. In Lviv, his best friend/roommate/poet encouraged him to join the hunger strike that grew and spread to Kyiv, culminating in the peaceful Revolution on Granite. Thought to be an energizing force that led to Ukraine’s independence when the Soviet Union collapsed.

After protesting in Lviv, Ivan becomes terrorized by what he believes is a Soviet spy after him, evoking a black-and-white spy chase thriller. “The tension he felt was unhuman, unbearable.” So he flees to his childhood home, doubting he was ever courageous. This is the haunted state of his psyche when he steps into the fraught marriage.

If you believe “writing and reading are revolutionary acts that can and should change the world,” as Will Evans does, founder of Deep Vellum, the largest indie US publisher of translated books, then you’ll appreciate Nina Murray’s translation. A poetess too, from Lviv, the Cultural Capital. Ivan’s home in Uzhhorod, a small city in the Carpathian Mountains southwest of Lviv, is where the author is from.

Atmospheric prose distinguishes one ancient city from another. Kyiv the beautiful one, with its riverbanks and pedestrian bridge over the Dnieper River (“no other city in Ukraine could boast a waterfront so European, so Parisian!), compared to Lviv, “cavernous, gray, full of spires,” and where “the entire community had developed its own strategies of resistance and survival.”

By Mstyslav Chernov [CC BY-SA 3.0] via Wikimedia Commons

© Raimond Spekking / CC BY-SA 4.0 (via Wikimedia Commons)

Margita highlights Ukraine’s great ethnic diversity (100 different nationalities). She’s from Transcarpathia bordering Hungary. Regions are depicted as having different political parties, besides the traditional cultural uniqueness, owing to the historical reshuffling of territories and boundaries. This explains why pálinka (Hungarian vodka), holybtsy (stuffed cabbage) and other dishes flow through Ivan’s home, and why this minority group is looked down upon by those Ivan encounters, who seem to believe Ukrainian-Hungarians may be more susceptible to Soviet/Russian influences.

Citing Gabriel Garcia Marquez and Carlos Castaneda’s “psychedelic texts” enlarges the philosophical/existential quality of the novel. Stus’ “The Road of Pain” poetry collection said to speak of the worst kind of mental and physical cruelty (Soviet solitary imprisonment and grueling labor camps) and yet he found the strength to write uplifting poems. “The debris of torment/might give birth to flowers” sums up Ukrainian empowerment.

“Ukrainians know fear. They also know how to overcome it.”

Lorraine