A fantastical, fanatical escape from reality (nameless town and mountain retreat 100 miles away; present-day and replica of a late 1970s setting): If you had all the money in the world, what would you do with it?

Thirty-six-year-old Bonnie Lincoln, who lives alone in a trailer park, has “longed for something more, something extraordinary.” So when she wins a jackpot lottery, she knows exactly how she’ll spend it.

At long last, through sheer luck, Bonnie’s fantasy to transform her life and adopt a new identity has come true. A random event breaks the luckless cycle of her life. For someone who’s wondered “What decides a life?” and what “determines one’s identity?”, finally she has the power to control the answers to those fundamental life questions.

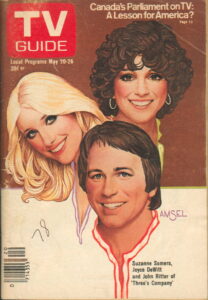

What’s her fantasy? “To crawl into Three’s Company and live there” – literally. Obsessed with the hugely popular, influential sitcom that aired on ABC for eight years, from 1977 to 1984, Bonnie actually wants to recreate the set and assume the identities of the three starring roommates of the show, all comedians:

- Handsome, charming, clumsy John Ritter who played Jack Tripper, and shocked fans when he died suddenly at 54;

- Sexy Suzanne Somers who played the stereotypical dumb blond-bombshell Chrissy Snow; and

- Cute, dark-haired bobbed Joyce Dewitt as Janet Wood, the most practical of the bunch.

(You can watch the show for free on Pluto TV.)

The utterly imaginative plot of terribly lonesome Bonnie wanting to wrap herself up in the nostalgia of a mad cap comedy featuring three single, good-natured, and good-humored friends is an awfully appealing plot. For about a third of the novel, it absurdly is.

Ashley Hutson makes her splashing debut in what turns out to be an emotional and psychological tsunami – the last third of the novel. The middle third is the transition from Bonnie’s small, downtrodden world to an artificial, fake reality. Hutson may have watched all 170+ episodes of the TV show to so meticulously depict, down to every minute detail, Apartment 201 where Jack, Chrissy, and Janet lived together (and more), to have enabled Bonnie to slip into a surreal world she funded and had built, replicated with off-the-charts authenticity to allow her to forget her reality.

It’s hard to pinpoint when Bonnie crosses the line from starry-eyed, nonsensical to eccentric to crazed, because her descent doesn’t happen overnight and Hutson moves us back-and-forth in time and place so we’re not focused on her losing touch with reality compared to entertaining us with clever prose and impressive details that seduce us. By the time we realize what’s going on, that the enchanted plot gets darker and darker, that talented Hutson has a more complicated literary mindset than the light-hearted, humorous one we thought we were reading, we’re hooked, riveted, no turning back.

So, this review comes with a warning. Given all that Bonnie has lost, which we learn early on, it seemed perfectly reasonable she’d find a healthy escape from her traumatic life by binge-watching a wonderfully funny and cheerful TV show that let her escape from the unrelenting boredom of spending twelve years of her life working at a mom-and-pop store that could be anywhere in small-town America. We’re glad to see Bonnie has moved on from two traumatic losses early in her life: the death of both of her parents, each to self-destructive behaviors, one after another.

Bonnie doesn’t have any siblings. Her childhood friend Krystal is like the sister she’s never had, loyal and caring, whereas Bonnie is aware she vacillates in “passive aggression” towards the only friend she has. It’s Bonnie’s parents who own the grocery mart she works at, having felt feeling sorry for her plight in life, going further, welcoming her into their family that includes Krystal’s brother. Descriptions of their Christmas celebrations all together are the dreamy Hallmark kind, complete with a “Christmas village” and all the holiday trimmings. Bonnie now has a happy family to love, unlike hers, until tragedy strikes again. In the aftermath, Bonnie keeps pushing Krystal away. At what point does Bonnie stop trusting anyone?

Bonnie is more troubled than we thought. Hutson does a brilliant job depicting the disintegration of her fragile, traumatized, mental state. The accumulation of grief, loneliness, insecurity, and longing rages underneath. We bear witness to Bonnie’s unraveling into madness. Even so, we’re caught off guard at how far gone she is.

Hutson is after a larger message than what happens to the deeply disturbed character she’s created. She’s reflecting what’s happening in America: disintegration as it relates to the mental health crisis and the surge in violence. This is fiction that tells us is we cannot fix deep-seated societal problems without understanding the depths from where they come. Although the novel turns out to be so different than expected, Hutson has her pulse on this phenomenon.

In an interview, the author sums up how her novel went from humorous to depressing:

“Humor both tempers and reinforces despair. Humor is something that should lift us up, but when it turns to cynicism about our reality it often puts us back down lower than where we started.”

Another interview enlightens us more. “I like being disturbed,” she says when asked about her reading preferences. In accomplishing what the author set out to do, she disturbs us for a higher purpose: to provoke us so we can ponder how we might contribute to altering the trajectory that’s been defining and disturbing America. We feel sad because what’s happening in fiction is imitating the unspeakable sadness of countless people feeling left out, abandoned, helpless, and scared so they end up resorting to violent acts against themselves, their families, and strangers, young and old. Bonnie didn’t feel safe anywhere so she went about creating a self-enclosed bunker of sorts where no one could hurt her, nor find her. Even Krystal has no idea what she’s been planning, or where.

To make the impossible possible, Bonnie stealthily contracts a lawyer and fifty-men to construct her fantasy in the mountains, also in an undisclosed location. The hoops she makes people go through to execute her wild plans and the way she treats them, the kinder getting the worst treatment, is harsh, cruel. Despite knowing how far people will go for money, it still amazes and pains us.

Although Bonnie has been through a lot to no fault of her own, we’ve lost our empathy for her. We don’t have to like a character to recognize the potency of her invention. We don’t have to like her in the same way we don’t like what’s happening in America to Americans, but we ought to care and recognize how far off we’ve come from our “better angels.”

Bonnie’s story could be set almost anywhere, although the setting feels more eastern mountains than western. Perhaps because the author lives in Maryland and it doesn’t feel anywhere near Santa Monica, where Three’s Company was filmed.

When does trauma and despair cross into a mental disorder? As Bonnie’s fury against humanity deepens, we’re diagnosing her. Schizophrenia? Multiple personality disorder? Post-traumatic disorder? All the reader knows is that she’s become seriously unhinged.

Bonnie Franklin is one of the most distrustful, fearful, disturbed, and loneliest characters we’ve met fictionally. Well, at least reviewed here.

Lorraine