ILLUMINATING BEAUTY AND FEMINISM IN THE MIDDLE AGES (California, New York, England, France; 21st century sweeping into 14th century to early 15th): “Medieval sleuthing” cannot be rushed. Savor this brilliant, richly-detailed historical novel that vividly takes us back to the late medieval era, alternating with 2018 modernity.

Venturing into the medieval period, new for this blog, might not be the case if Cities of Women weren’t so entrancingly written, enlightening, and relevant to our historic era.

Ten years of scholarly research by Kathleen Jones, professor emerita at San Diego State University women’s studies program, triumphantly transitions to historical novelist.

That doesn’t mean you shouldn’t concentrate as Jones invites us to put on our detective-thinking caps in this medieval whodunit. Not a murder, but an art mystery as to who exquisitely embellished a coveted medieval “Illuminated Manuscript”? (See definition here.)

Created for religious purposes, royalty, and others before paper was invented, the art of illustrating glimmering manuscripts applied delicate gold leaf and brilliant-colored paints along the borders of impossibly hard-to-decipher medieval handwriting scripts, on parchment or vellum (see description, differences, images here), reflects a fervent “determination to bring beauty to life” during the dark Middle Ages.

Dedicated to “invisible” women artists, Jones’ modern-day protagonist, Verity Frazier, is seeking tenure at a California college, depicting what 21st women in academic settings go up against – the pressures of academia to publish and gender assumptions.

On page one, we learn that Verity’s feminist scholarly interests mesh with her personal preference for female lovers, thus the knowledge, instinct, and sensitivity she brings to bear is a strong belief that the mystery artist was a woman not a man as medieval historians claim and later ones presume too. It’s not that a man couldn’t arrive at the same hunch, but likely not as acutely as Verity, arguing that “the only architects of beauty” weren’t only men” – “as if vision had only one sex.”

Verity is willing to risk tenure to find evidence to alter art history and her tenure chances since she’s been longing for something more radical.

The hunt for a medieval female artist buried in history proves elusive and transporting. Splendid atmospheric prose combined with unknown familiar history and art is charismatic.

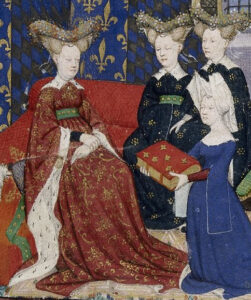

Historians know who wrote the manuscript, but not the name of the artist who adorned it with intricate artistry and devotion: Christine de Pizan was prolific, “regarded as one of Europe’s earliest female professional writers” (https://blogs.bl.uk/digitisedmanuscripts/2013/06/christine-de-pizan-and-the-book-of-the-queen.html). The British Library’s online comments and images, refers to this medieval manuscript as “one of our best-loved (and most-requested).”

Verity takes us to the London-based library, considered one of the greats and largest, on her quest to pursue truth, accountability, recognition. Housed in their Treasure Gallery, Christine’s stunning manuscript survives. Commissioned by the Queen of France, Isabeau of Bavaria who reigned in the early 15th century, it’s called The Book of the Queen or Harley 4431. Jones describes how and why this extraordinary work came to be.

Alternating mostly between the 1300s and 2018, the medieval chapters consume much of the story. Opening when Verity is late submitting her dissertation, only the final chapter left. Interestingly, it’s already been critiqued for not sounding scholarly, rather in the writing style of a novelist. Cleverly mirroring what Jones has done.

Prior to leaving America for Britain, Verity attends a medieval lecture and exhibition in Manhattan at the Morgan Library, J. P, a voracious collector.

There she stumbles on a mesmerizing medieval painting an astute female librarian notices her admiring.

“Tantalized by its central image: a large initial C decorated in the brightest blue she’d ever seen. The initial was fitted inside a square illuminated in glittering gold, while out of its edges tumbled tendrils of vines and other flora in red and green, with gold-flecked flourishes . . . the longer she stared, the more it seemed as if the gold-embossed letters, tendrils, and halos were some kind of multidimensional time machine: incandescent, ethereal, and luminous, transporting meaning beyond the ordinary boundary of understanding. It was like seeing dust burst into flames.

“She took out her notebook and wrote one word: Beauty.”

Creating Beauty, the primary theme, shows why women seek “beautiful things” in the darkest of times.

Other important themes include Learnedness, Integrity, Justice, and Reason. Leading female characters choose to tell stories of “charity and goodness and the welcoming embrace of a community of women” instead of dwelling on the darkness. The Morgan librarian is pivotal, suggesting Verity read Christine de Pizan’s Book of the City of Ladies. From there, the sleuthing ignites.

This timeless, affecting story portrays women standing up for their beliefs and values no matter the odds against them, or the sacrifices they have to make.

Verity reasons that for a female to climb the ultimate echelons of respect for her talent during the medieval ages when knights, kings, clergymen reigned supreme, Christine wouldn’t choose a man to partner with. So who was the female medieval artist Christine trusted with her life’s work?

History is shown to repeat itself, including personally when another woman, a professor from France notices Verity at another library, this one in London. Her scholarly interest in medieval women isn’t new, like Verity’s (who specializes in 19th century female French revolutionaries), so she offers to assist with her research, also leading to a tender love affair fraught with jealousy on the part of Anastasia. A name that becomes very significant in the investigation.

Past and present history also converge with wars and a pandemic. During this medieval timeline, The Hundred Years War between France and England and The Black Death (bubonic plague) happened, each killing millions. The Great Plague, history’s worst, millions more.

Poverty versus wealth; the hypocrisy of sacred values and sexual abuse in the church; transformative childhood influences; and human emotions that run the gamut from grief, loss, lust, violence to love. All stand the test of time.

Moreover, Cities of Women shows people with divergent agendas coming together. Can that comparison between the ages happen today?

You’ll be introduced to technical words in the laborious process of making parchment or vellum, creating “suede-like” sensations derived from drying and stretching the young skins of cows, sheep, and goats. Single pages of medieval manuscripts are called “orphaned leaves;” a double page “bifolia”; a collection of pages “quires”; bound pages transformed into a book “codex.” Artistic embellishments were intended to push past the ugliness” to “make beauty burst into it like a bright light.”

Paris is seen as a thriving center of medieval paper-making for book publishing. Today, when you walk along the Left Bank of the Seine you’ll still see booksellers lined up but their status is unclear because of the upcoming Olympics.

The energizing spirit of persevering women artists in the face of atrocities and adversities is palpable. Makes you wonder how many other great women of the arts have yet become visible.

Lorraine