The noble mission of animal photography (present-day, with a look back on 180 years of photographic history; worldwide): You cannot come away from this out-of-this-world, unique visual and narrative reading experience without thinking of your own behavior towards animals. The noble mission of Why We Photograph Animals.

Can a “camera artist” capture an extraordinary animal moment to make a difference?

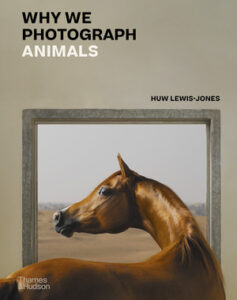

This weighty “visual essay” – coffee table-sized, 335 pages printed on heavy, glossy recycled paper magnificently showcases the art of animal photography – befitting the weighty raison d’être of the compilation.

Told from current and historical perspectives by versatile British author Huw Lewis-Jones, he traces over 100 animal photographers including thirty-six he interviewed based around the world (in sections called “Profiles” and “Insights”), along with 300 color and black-and-white illustrations, the book is “soul-searching.” Aimed at educating, encouraging, and inspiring all who don’t see, ignore, or existentially appreciate the integral and vital role wild animals have on the health and future of our planet. (Livestock and dogs are included but far less).

Can photographs of awe and shock engender enough “empathy and compassion” to change the course of what’s already happened? A whopping 200 species every day becomes extinct! The impossible is on every page.

Lewis-Jones offers a balance between the beauty that still exists globally and the devastation humans have caused or contributed to, intentionally or not. This book is as stunning and triumphant as it is sorrowful and critical.

The author is humble. This isn’t a book about him, yet it speaks volumes about his values and passions. He’s among the arctic photographers he interviewed and presented a few of their award-winning images, Lewis-Jones is also a wildlife photographer who’s been on twelve polar expeditions, some he led. He’s also an environmental and photographic historian, who’s written numerous books for both adults and children. Delightfully switching from serious to fun books, making it obvious he’s an educator too. In fact, the Associate Professor of Environment and Culture, and Marine and Natural History Photographer at Falmouth University in Cornwall, England. Inspiring youth about the wonders of the animal world fits his goals for Why We Photograph Animals: to provoke thinking on the whys we photograph not the hows – the more conventional type of wildlife photography book.

The image of an Asian elephant “forced” to swim underwater for a crowd of tourists, adults and children, taken by Adam Oswell (scroll down to see: https://weanimalsmedia.org/2021/11/10/interview-with-wildlife-photographer-adam-oswell/) at a Thailand zoo makes it clear both audiences need educating. In this case, on animal exploitation.

Lewis-Jones has the greatest respect for Sir David Attenborough, “arguably the greatest wildlife broadcaster.” A broadcaster too, he also admires the powerful and tireless camera work of the photographers he’s broadcasting in a literary sense.

It’s impossible in this space to describe the amazing work of all the photographers assembled for this extremely ambitious book, which seems almost impossible to imagine amassing and gathering together on such a large scale. A few are highlighted below.

Asking the same questions to varied types of wildlife photographers and cinematographers, one naming who influenced their work, three answered Ami Vitale. So let’s start with her, since their common response correlates with Vitale considered “one of the most influential conservation photographers of her generation.”

She took the image she branded The Last Goodbye on assignment for National Geographic in Kenya. Based out of Montana, she’s filmed in over 100 countries. This haunting image marked the last moments in the life of the world’s last northern male white rhinoceros, when there used to be “hundreds of thousands” roaming earth. She wrote that when her picture appeared on the October 2019 cover of the magazine’s The Last of its Kind: What We Lose When an Animal Goes Extinct issue. The man whose hands and head gently soothe the animal had been caring for him at the Ol Pejeta Wildlife Conservatory. She says, “It felt like watching over our own demise.”

We feel the ranger’s grief. Is that why this precious rhino photograph moves us so much? Holding up a mirror to the grief many are writing about in memoirs in the recently minted grief genre? What role does isolation and loneliness play in the Age of Loneliness cited, in this era of human and environmental crises?

Googling we learn there’s two female northern white female rhinos left in the world. Scientists reported in January 2024 successful efforts underway using in vitro fertilization to save the species. Hope can be found here, and elsewhere in the book.

Another breathtaking image, this one stark black-and-white, touches a deep chord. Taken closer to home at New York’s City’s Bronx Zoo in 1995 by Britta Jaschinski, a Wildlife Photographer of the Year, her affecting photograph is of a trapped beluga whale. The whale’s white head appearing dolphin-like friendly, big eyes, and part of a long body stands out under black water. Viewed in between two dark corrugated open doors that can shutter this very social and intelligent animal up, captioned Captive, a singular photograph tells the story of imprisonment of wild animals isolated from their natural habitats.

By pelican [CC BY-SA 2.0] via Wikimedia Commons

Two other images Jaschinski shot continue to depict the captured theme. Gruesome, they’re almost too painful to look at. One is a gorgeous zebra’s head sliced below the neck – a hunter’s trophy – sitting in a grocery cart on its way to an unimaginable place that stores hunted down animals at a facility in Denver, the National Wildlife Property Repository. Who ever heard of such a thing? Run by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service it contains 1.5 million animals according to their website. The other cringe-worthy too photograph reveals about fifteen shelves stuffed with Leonard Skins Tanned covered in plastic. She says, “If it weren’t for photographs, the world’s conscience would whither.”

You couldn’t get a more personal or popular animal to photograph than dogs, apparently the top type of digital image downloaded worldwide. Three million a day! And yet the image of one of Traer Scott’s Shelter Dogs that was euthanized, a pit-bull mixed with a Great Dane, stares straight at us with piercing eyes and a solid stance that beseeches us. Scroll down to the fourth image to see the photograph: https://mymodernmet.com/heartbreakingly-beautiful-portraits-of-shelter-dogs/.

Tim Flach gives us another canine perspective with the most adorable group of Dalmatian puppies huddled together, with their newborn pink skin, sleeping.

Stefan Christmann writes about the “good” and “bad” photos as a reflection of “how we act as humans.”

Among the whys are also for good and bad purposes. Altruistic, joyful, and valuable ones for scientific research; education; global warming and wildlife conservation (consistently cited); adventurism; and preserving remarkable animal moments for “posterity.” The bad are greedy – trophy hunting and profit motives. Where does our lack of understanding the critical importance of animals in the health of ecosystems fit?

This isn’t dry storytelling. It’s stirring, soaring, and disturbing.

Lewis-Jones presents the best and worst of us. On how we “look at the world.” With all its splendor, diversity, and “weirdness” amidst the “dread.”

The “how we photograph” has changed, but it’s the why that emotionally resonates.

Lorraine